Care.. Discover.. Teach.. weill

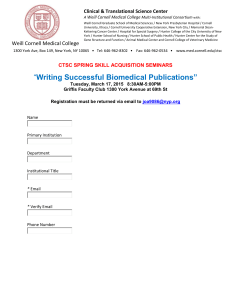

advertisement