Policing Elvis: Legal Action and the Shaping Contested Space DAVID S. WALL

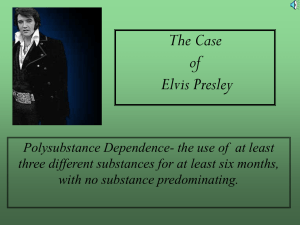

advertisement