Governing Nightlife: Profit, Fun and (Dis)Order in the Contemporary City

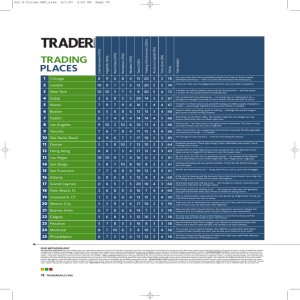

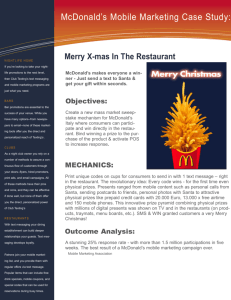

advertisement