Graduation Ceremony 20 Graduand’s Speech

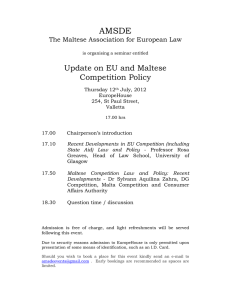

advertisement

Graduation Ceremony 20 Monday 7 December 2015 at 1630hrs – Jesuits Church Valletta Graduand’s Speech Sarah Grech One of the first warnings I received as I began postgraduate research, was that I should prepare for this to be a lonely experience, but, as I have reflected recently, I feel fortunate to find that it has not been such a solitary process after all. Sometimes, support came in the shape of extras teas, or the occasional pointed question "Have you finished yet?"/"Għadek għadejja xbin". At other times, the support came through debates with my tutors at the Institute of Linguistics, and colleagues and fellow postgraduate students. I am grateful for all those occasions where the generosity of others made me keep my feet on the ground, and challenged me to become more knowledgeable in my chosen field. I know that my fellow graduands can also gratefully call to mind a few special people who challenged and encouraged them in their own studies, too. Many of you who accompanied us most closely on this journey are here today, so this proud occasion is your moment too. On behalf of all the graduands, I would also like to thank the University of Malta, and specifically the members of its governing body and its administration. Many of them are here today, attentive to every detail, to ensure that this event is a success; there are also quite a few others we have probably never even met, but who still might have made our journey that little bit smoother, sometimes without our even realising it. I wonder if some of you can call to mind an incident where somebody from Malta is immediately recognised as Maltese, just by the way they speak, even though they are speaking in English, and even though they might be abroad. You might yourself have been sitting in an airport lounge somewhere, and suddenly heard an accent which you immediately identified as your own. The fact that native listeners of a language variety, or dialect, can quite accurately identify someone as a native speaker, or not, was a focal point in my research for a Ph.D. in Linguistics, because it suggests that there is something socially meaningful there that is worth identifying. Although we often tend to think of languages in terms of their ideal form, linguists often remind us that real-life language is rarely pristine, and carries far more information, also about its user, than an ideal prototype would ever allow for. In other words, we don't speak like robots. We speak like human beings, and because as humans, we are all quite different, it follows that the language varieties and dialects we use reflect our differences in many ways. Funnily enough, we're not always that accepting of these differences. A native listener can almost instantly identify another speaker, but we rarely stop there, as we often go on to measure up that speaker according to our own, internalised standards, such as that they are ill-educated, or snobbish, or from a particular town, and so on. My thesis focused on capturing the first knee jerk reaction, but without the added judgment. The dialect I focused on was Maltese English so I'll leave you to imagine why I didn't want to capture the more judgmental attitudes in this case. Instead, I felt it was useful to describe Maltese English as it is used here in Malta, but not with reference to another standard variety, where the temptation is simply to regard ours as wanting, in comparison. Rather, it is often in examining language variation on its own terms that we can begin to understand its place in our society. In Malta, more people use English now than in the fifties and sixties. Unlike then, it is not just the lucky few granted an education who get access to English, but the entire population. In a fit of nostalgia, we might say we prefer the sixties version of one proper English. And by proper, we probably mean something approaching Standard British English. But the reality is that that type of English has little meaning for us today, because we don't form part of the society where that standard variety is spoken, if indeed it is spoken, but that's another matter. Instead today we are faced with variation in both our official languages, together with quite a few others, which resists being categorised. Does this mean that we are going to descend into some abysmal linguistic chaos of pidgin Maltese English, where both Maltese and English, and any other languages are corrupted beyond recognition? Since the average person is well aware that English is still a useful language for international communication, and that Maltese is the home language, it is plausible to suggest that this is not a realistic threat. It is plausible to suggest, that with a combination of awareness, and education – particularly in the education of the very young – we will in fact draw on our multilingual nature and be sensitive to when, and when not, to use different forms of all the languages available to us. In fact, we already do this all the time, as any Gozitan will tell you, when they switch from their dialect, to the standard dialect of Gozo, or to Maltese, as the need requires. There is no reason to expect that the same should not happen with all our languages especially if we are confident that this is one way to ensure their very survival. After all, nature not only thrives in diversity but depends on it for survival, and Language is part of our nature. Linguistics is concerned with the study of Language, and yet, in Linguistics we are also committed to forging links between other disciplines in our quest to understand more about this most human of activities. My own research has led me to work on English and Maltese language and linguistics, on interpreting studies and on History; and I can also consider Forensic Linguistics too. This multidisciplinary research has been an important learning curve and I would encourage every graduand today to consider the benefits of reaching beyond our immediate specialisation as we look to our future now. This might be a strange thing to suggest as we are congratulated precisely for having managed to focus on a very specialised area of study and yet, hopefully it is not so strange. Law, Entrepreneurship and Music, I am sure, would all benefit from conversations across all sorts of boundaries. I leave it to you to decide on the details of how or when or indeed why at all, such conversations might help us to continue refining what we do. Thank you.