IS THE KITCHEN THE NEW VENUE OF FOREIGN

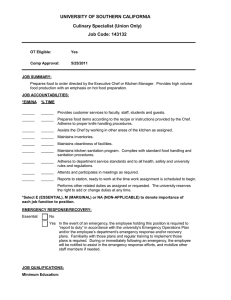

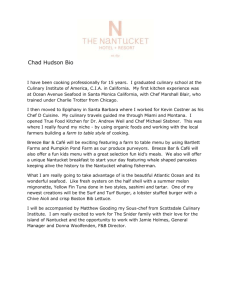

advertisement