Background Checks for Firearm Transfers Garen Wintemute, MD, MPH Violence Prevention Research Program

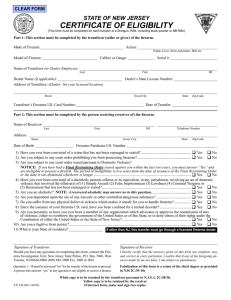

advertisement