Document 13245544

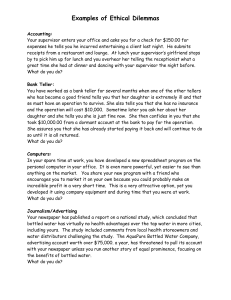

advertisement