International adaptation finance: benefitting the public or the private?

advertisement

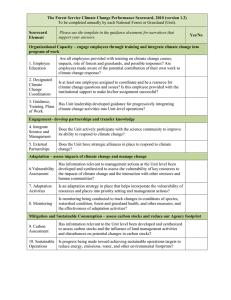

International adaptation finance: benefitting the public or the private? Åsa Persson, Stockholm Environment Institute & Stockholm Resilience Centre “In the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation, developed countries commit to a goal of mobilizing jointly USD 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries.”countries. Between countries? Between countries? Between projects? Between countries? Between individuals within countries? Between projects? Between countries? Between projects? Between individuals within countries? Between individuals between countries? Between countries? Between projects? Between individuals within countries? Between individuals between countries? Equity vs. Efficiency? • Watershed management in a Honduras urban slum area • 1 million indirect beneficiaries • $4 per person • Farm-level investment support in livestock sector in Uruguay • 500 farms • $3,500 per farm Outline • Policy context: adaptation is being institutionalised as a policy issue and public spending item, with a political economy emerging • Why and how is adaptation finance justified? Adaptation for whom? Benefitting the public or the private? • Adaptation benefits • Government intervention rationales • Empirical evidence from the Adaptation Fund The need for adaptation finance (annualised flow, billion USD) 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Est. Need CopAcc Long-term CopAcc Fast Start Previous ODA (0.1) AF (0.1) The need for adaptation finance (annualised flow, billion USD) 100 90 80 70 60 50 GAP 40 30 20 10 0 Est. Need CopAcc Long-term CopAcc Fast Start Previous ODA (0.1) AF (0.1) UNFCCC funds: Adaptation Fund • Established under the KP, financed by share of proceeds from CDM and voluntary contributions • Majority of developing countries on the Board and direct access • Funds ’concrete adaptation’ • Scale: 370 million available 2009-2012; 93 million per year • Disbursed: 70 million (11 projects) • Future uncertain after Kyoto expires UNFCCC funds: Green Climate Fund • Transitional Committee to present design in Durban • Supply of finance not within its mandate – ’challenging but feasible’ (see AGF and G20 reports) • Business model still not determined – ’main global fund’? – Comprehensive fund with large secretariat including existing funds as windows – Complementary fund specialising in leveraging private sector finance • Balanced allocation between adaptation and mitigation – two windows • Focus on governance issues: equal Board representation, direct access Multilateral funds: World Bank PPCR • Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience, part of CIF • Pilot countries selected partly based on vulnerability assessment (9 countries, 2 regions) • Country-driven through formulation of Strategic Programs • Equal representation of donors and recipients on committee • Scale: 987 million pledged (60% grants) • Disbursed: 323 million • Future uncertain, CIFs have a sunset clause Bilateral funding and development aid • Specific adaptation projects and ’climate-proofing’/mainstreaming initiatives • No agreement on how to assess what is ’new and additional’ in relation to current ODA budgets and targets (0.7%), i.e. how to ’MRV’ adaptation finance • Scale: lack of methodology – 100 million per year (2001-2006) (Roberts et al. 2007) – 3,963 million from three BFIs in 2009 (UNEP 2010) • Future uncertain due to evolving institutional architecture, MRV practices, budget austerity The link with development Vulnerability focus Addressing the drivers of vulnerability Activities seek to reduce poverty and other non-climatic stressors that make people vulnerable Impacts focus Building response capacity Managing climate risks Confronting climate change Activities seek to build robust systems for problem solving Activities seek to incorporate climate information into decision-making Activities seek to address impacts associated exclusively with climate change McGray et al. (2007) richard.klein@sei.s e The link with development finance Vulnerability focus Addressing the drivers of vulnerability Activities seek to reduce poverty and other non-climatic stressors that make people vulnerable Traditional development funding Impacts focus Building response capacity Managing climate risks Confronting climate change Activities seek to build robust systems for problem solving Activities seek to incorporate climate information into decision-making Activities seek to address impacts associated exclusively with climate change New and additional funding richard.klein@sei.s e Accountability vs. Effectiveness? • Mobilising new and additional 100 billion – an issue of trust and accountability vs. • Improving ’climatecompatible development’ practices Accountability vs. Effectiveness? • Mobilising new and additional 100 billion – an issue of trust and accountability vs. • Improving ’climatecompatible development’ practices • Not a trade-off, but unlikely with clear-cut boundaries between climate finance and ODA The political economy of adaptation finance • The finance gap not likely to be closed in near future, but still serious inflow of new money • Commodification of carbon – commodification of adaptation? • ”Processes by which ideas, power and resources are conceptualised, negotiated and implemented by different groups at different scales” (Tanner and Allouche, 2011) – Who control the funding institutions? Formal and informal power – Growing market, project management revenues worth up to 100 million – Increasing interest from the private sector – Risk of corruption Need to broaden the focus • Current focus on supply side and institution-building • Need to expand to consider beneficiaries – Targeting the most vulnerable • Debate on vulnerability indices Vulnerability indices • Academic work (e.g. Haddad; Buys et al; Barr et al) • Impossible to objectively construct indices, since ultimately rest upon normative values around what constitutes vulnerability (Klein; Hinkel; Füssel) • Yet, new attempts addressing policy-maker demand – – – – Global Adaptation Index 2011 Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2010 ActionAid – climate and food vulnerability index 2011 PPCR selection of countries Need to broaden the focus • Current focus on supply side and institution-building • Need to expand to consider beneficiaries – Targeting the most vulnerable • Debate on vulnerability indices – Maximising benefits and prioritising benefits of public rather than private nature • Private vs public good properties of adaptation • In practice, how many and which individuals benefit from an adaptation investment? • More pressing for adaptation than mitigation finance, since although some CDM benefits are private (profits) there are clear global benefits of equal per capita character Private vs. public adaptation • IPCC definitions: – Private: ”adaptation that is initiated and implemented by individuals, households or private companies” – Public: ”adaptation that is initiated and implemented by governments at all levels” Anticipatory Reactive · Changes in length of growing season · Changes in ecosystem composition · Wetland migration Private · Purchase of insurance · Construction of house on stilts · Redesign of oil rigs Public Natural Systems · Early-warning systems · New building codes, design standards · Incentives for relocation Human Systems · Changes in farm practices · Changes in insurance premiums · Purchase of air-conditioning · Compensatory payments, subsidies · Enforcement of building codes · Beach nourishment Externalities and public goods related to adaptation • Some adaptation actions have positive externalities – individuals have an incentive to undersupply those, hence role for government support (Leary; Mendelsohn) – E.g. irrigation (private) vs. plant breeding (public) • Adaptation as providing or protecting public goods – nonrivalrous and non-excludable – E.g. seawall (club good), prevention of temperaturesensitive disease carriers • Use government support in cases where positive externalities or public good at stake to enhance allocative efficiency Three dimensions of benefits • Private benefits only or positive externalities (public benefits) – No. of beneficiaries and concentration of benefits – sliding scale – In politics: inclusivity, non-discrimination, regulatory capture • Scale – Local up to global • Direct and indirect benefits – Delimitation of sequence of effects from an adaptation investment Private and public benefits - across scales Local private benefits Local public benefits Global public benefits • Value of saved crop for farmer • Improved water storage for household • Flood-proofed urban infrastructure • Afforestation preventing landslide • Biodiversity protection • Control of infectious diseases Indirect global public benefits • Avoided migration • Lower price volatility Private and public benefits - across scales Local private benefits Local public benefits Global public benefits • Value of saved crop for farmer • Improved water storage for household • Flood-proofed urban infrastructure • Afforestation preventing landslide • Biodiversity protection • Control of infectious diseases Indirect global public benefits • Avoided migration • Lower price volatility • Direct public resources towards projects where more public benefits, as a function of – No. of beneficiaries – Size of benefits (possibly vulnerability-weighted) Other rationales for government intervention • • • • • Market failures (externalities and public goods) Policies and institutional arrangements – adaptation options and incentives may be constrained by counterproductive policies and institutions Behavioural barriers – individuals make sub-optimal and/or maladaptive decisions due to, for example, short-sightedness Limited capacity – individuals may sometimes lack adaptive capacity due to external circumstances (e.g., cannot control insulation if living in rented accommodation) and natural systems may lack resilience to anthropogenic climate change Distributional concerns – uneven distribution of impacts and different adaptive capacity within sectors, regions and social groups Local private benefits Local public benefits Global public benefits • Value of saved crop for farmer • Improved water storage for household • Flood-proofed urban infrastructure • Afforestation preventing landslide • Biodiversity protection • Control of infectious diseases Indirect global public benefits • Avoided migration • Lower price volatility Other rationales for government intervention • • • • • Market failures (externalities and public goods) Policies and institutional arrangements – adaptation options and incentives may be constrained by counterproductive policies and institutions Behavioural barriers – individuals make sub-optimal and/or maladaptive decisions due to, for example, short-sightedness Limited capacity – individuals may sometimes lack adaptive capacity due to external circumstances (e.g., cannot control insulation if living in rented accommodation) and natural systems may lack resilience to anthropogenic climate change Distributional concerns – uneven distribution of impacts and different adaptive capacity within sectors, regions and social groups Local private benefits Local public benefits Global public benefits • Value of saved crop for farmer • Improved water storage for household • Flood-proofed urban infrastructure • Afforestation preventing landslide • Biodiversity protection • Control of infectious diseases Indirect global public benefits • Avoided migration • Lower price volatility Other rationales for government intervention • • • • • Market failures (externalities and public goods) Policies and institutional arrangements – adaptation options and incentives may be constrained by counterproductive policies and institutions Behavioural barriers – individuals make sub-optimal and/or maladaptive decisions due to, for example, short-sightedness Limited capacity – individuals may sometimes lack adaptive capacity due to external circumstances (e.g., cannot control insulation if living in rented accommodation) and natural systems may lack resilience to anthropogenic climate change Distributional concerns – uneven distribution of impacts and different adaptive capacity within sectors, regions and social groups Local private benefits Local public benefits Global public benefits • Value of saved crop for farmer • Improved water storage for household • Flood-proofed urban infrastructure • Afforestation preventing landslide • Biodiversity protection • Control of infectious diseases Indirect global public benefits • Avoided migration • Lower price volatility Constructing an analytical framework: Efficiency and equity • Efficiency: allocation of resources that maximise net social benefits • Equity: distribution of resources/benefits perceived as fair, e.g. equal lump sums (equality) or in proportion to level of vulnerability • Definition and weighting of benefits Constructing an analytical framework: Adding the international layer • At national level – government chooses rationale (or mix of) • At international level – rationale can be chosen in respect to – Country level OR – Individuals/sub-national groups Subnational variation in vulnerability and adaptive capacity O’Brien 2004 Rationales for adaptation finance Global III. •International redistribution of wealth according to some principle, e.g., ’particular vulnerability’ I. •Support climate adaptation with transboundary /global benefits Market failure Distributive IV. II. •Support (sub-) national policies for adaptation, which prioritise or are restricted to providing public goods and addressing market failures •(Sub-)national distribution of wealth (externally provided) to address adaptive capacity limitations or uneven distribution of capacity Local Implications for allocating adaptation finance Empirical evidence from the Adaptation Fund • Which rationale is being applied in practice? • Review of funding criteria and guidelines, proposals and decisions 1. 2. 3. 4. Type of adaptation proposed Allocation between countries Allocation between individuals and groups (project level) Identification of adaptation benefits Submission of project proposals • Legal basis in Kyoto Protocol: – ”to assist developing country Parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change to meet the costs of adaptation” • Called for proposals in April 2010 • • • • • Projected funding available 2010-2012: USD 370 million Has received 36 proposals (34 countries) Has funded 11 projects Total funding requested: USD 222 million (60%) Average funding requested: USD 6.9 million • Proposal review: not publicly accessible 1. Type of adaptation proposed I • Guidelines – Minimal guidance on what constitutes ’concrete adaptation’, in terms of type of activities and priority sectors – Strategic Results Framework specifies 7 desired results, of which 3 can be considered ’concrete’ • Proposals – Typical sectors: agriculture, water, coastal management – Mix of government investments in physical assets and decentralised building of adaptive capacity – Lack of budgetary breakdown of project components 1. Type of adaptation proposed II • Decisions – Sectors as above – No clear pattern regarding types of activities • Link to efficiency/equity rationales: – Hard to generalise and associate types of adaptations with private vs public benefits, depends on implementation 2. Allocation between countries I • Guidelines – No definition or indicators for ’particular vulnerability’ – Eligible countries still 149, no priority for SIDS and LDCs – Equal national caps of USD 10 million • Proposals – Ad hoc and diverse justification of vulnerability – Scoring on vulnerability indices – no priority for particularly vulnerable – 33% LDCs and 30% SIDS – capacity problem – Funding requested per capita: from USD 2,250 (Niue) to 0.4 cents (India) – 6 orders of magnitude Comparing with vulnerability indices – Barr et al. 2010 • 131 developing country rankings, in quartiles • Dark=most vulnerable; light=least vulnerable Benchmark Proposals Decisions Comparing with vulnerability indices – GaIn 2011 • 187 developed and developing country rankings, in quartiles • Dark=most vulnerable; light=least vulnerable Benchmark Proposals Decisions 2. Allocation between countries II • Decisions – No pattern wrt justification of vulnerability – 27% LDCs and 27% SIDS – Dollar per capita: 2 cents (Pakistan) to 29 dollars (Maldives) – 3 orders of magnitude – Unclear logic so far • Distributive rationale rather than market failure; equity (equality) prioritised over efficiency 3. Allocation between individuals and groups (project level) I • Guidelines – No criteria/guidance on how to ’target to most vulnerable communities’ – No need to explicitly identify or quantify beneficiaries • Proposals – No/weak reasoning around comparative level of vulnerability of project area – Less than half quantify number of direct and indirect beneficiaries, from 2 million to 500 households – Funding requested per beneficiary: USD 3,500 (Uruguay) to 96 cents (Tanzania) – 4 orders of magnitude 3. Allocation between individuals and groups (project level) II • Decisions – Scattered info on beneficiaries – Funding per beneficiary: from USD 1 (Turkmenistan) to USD 1,095 (Maldives) • International equity rather than equity at subnational level 4. Identification of adaptation benefits • Guidelines – Limited guidance on how to estimate benefits and how to consider alternatives • Proposals – Ad-hoc description of benefits, if any – Only two proposals explicitly identify alternatives • Decisions – No evidence that proposals that discuss benefits more extensively are more successful • Equity rather than efficiency rationale Implications for allocating adaptation finance Conclusion • Clearly ’equity between countries’ rationale, to the point of equality • In line with convention and national sovereignty, BUT this is problem when funds are scarce across countries – No mechanism for ensuring that money goes to the most vulnerable a) countries or b) groups within a country – No mechanism for ensuring that benefits are maximised (weighted for vulnerability) – No mechanism for ensuring that benefits are directed towards the public rather than the private Ways forward • Not an allocation formula based on maximisation of net benefits, but better methodology for assessing adaptation benefits • Rule of thumb regarding securing (some level of) public benefits, to minimise risk of regulatory capture • Governance mechanisms for citizens to hold their national governments accountable for sub-national allocation of adaptation finance (AdaptationWatch.org) • ”Not all things that can be counted count, and not all that counts can be counted” – Albert Einstein