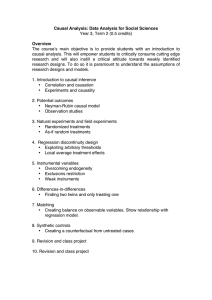

Appendix A Team Leader Tips and Tools Starting the Decision

advertisement

Appendix A Team Leader Tips and Tools Starting the Decision Protocol Decision Protocol 2.0 is designed to bring the decision team together to work through the decision process. As facilitator and/or team leader, you need to create and maintain a work environment where people can talk freely about past experiences and candidly express their desires and concerns about the decision they are embarking on. Make sure the group understands that anything developed in this process can be revisited and revised. The emphasis at first is on process, roles, and expectations, not content. Be tuned to relationships among the participants. Ask a few questions to see if there are any serious unresolved differences, strong ulterior motives, or autocratic leadership styles that might detract from the openness you are trying to achieve. It may be better to get some of these issues out in the open before you start. Emphasize that every team member’s opinion and judgment is valued. Encourage members to question each other across disciplines. They contribute as much by providing a source of professional and scientific thinking as by providing discipline-based facts. Display the Protocol cycles on a poster at all team meetings. At the beginning and ending of each meeting remind team members where they are and how their progress relates to cycles and questions that will follow. You may allow observers at the team deliberations, but do not let the observers formally and openly critique the Protocol, the team’s performance, or the substance of the discussions unless the team asks them. The team should work toward feeling comfortable and confident working together and with the Protocol. They should stay focused on the problem, which is difficult if they are looking over their shoulders for gratuitous advice or criticism. Throughout the Protocol are references to summary tables. Use flip charts or a computer projection system to record the interdisciplinary team answers and responses in these tables. Display this record so the team can check the pattern of their responses or refer to particular items. However, do not let the discussions turn into a game of racing to fill in tables without completely thinking through and agreeing on the responses. The team should bring all the materials (manuals, maps, plans, texts, literature, and so forth) about the situation, area, or proposed action to the first meeting. The team should view the area together either before the first session or during the first session, using the Protocol questions in the first two cycles to guide the field trip. 87 Following are some tips and tools for working through selected Core Questions. Not every Core Question has a tip or tool, but these will blossom as the Decision Protocol matures and your experience with it grows. PROCESS Cycle (Note: There are no tips or tools for PROCESS Core Questions 3 and 7.) PROCESS Core Question 1 Why are we here? What decisions have to be analyzed and made? An issue or problem that has been around a long time usually has at“’ tracted many proposed solutions, some with longtime supporters and opponents. Probe for insights about the history and the “maturity” of this decision. Has the organizational unit or others dealt with this before? Were the issues clearly defined in these earlier deliberations? Has the problem to be solved previously surfaced as a different issue? Why is it on the agenda now? Why is there urgency about getting the problem resolved? Avoid the following: ? ? Coming together to make a decision that has already been made. ? Not being open about what decision is being made in this process. ? i . . __‘ , ? PROCESS Core Question 2 Coming together to make a decision that really does not have to be made. Committing to or giving preferential treatment to a favorite proposal by describing the decision in terms of the proposal. Deiining the decision in terms of producing the analysis or an environmental document. The decision should be directed at solving some problem: the analysis or documentation should not be an end in itself. What are the appropriate geographic and organizational scales for this decision? Display a two-dimensional matrix to help people think about the scale issue. Rows would be labeled “Control” and “Consequences” and the columns would be labeled “Site,” “Landscape,” “Watershed,” “Forest,” “Ecoregion” or “District,” “Forest,” “Region, ” “National,” or some other breakdown. Use the matrix to guide the discussion. If the scale of the consequences and control seem to be larger than the team can address, consider involving teams from adjacent forests and organizations. PROCESS Core Question 4 What criteria will be used to solve problems in this situation? With this list, the team can get a feel for possible conflicts, trade-offs, and compromises and design a decision process accordingly. Developing the list will help establish a habit of being candid and clear about criteria and other judgments. Being explicit about criteria allows people to examine their own values and assumptions, ensures clarity among team members, creates an impartial 88 -_ “distance” from alternatives already proposed, builds a nucleus for negotiation and consensus, and stimulates creative thinking about designs for alternatives. Team members must eventually agree on criteria before they can agree on a final design. This may be the best time to get the deciding officer’s candid expectations and wants. Stay general at this point. Try brainstorming to develop a large list. This is not the final set of criteria. In the PROBLEM Cycle there will be an opportunity to refine, focus, and reconfirm the criteria through establishing objectives and consequence measures. Avoid premature criticism of possible criteria or letting one person dictate the criteria. It is important to discuss criteria before people buy into an alternative or become set on unspoken criteria. PROCESS Core Question 5 Who should be involved? Don’t concentrate on technical knowledge to the exclusion of qualities such as problem-solving skills, interpersonal abilities, or even enthusiasm and energy. Personal attributes are important. Such factors include experience with similar projects, knowledge of specific tools (if you think they will be used), knowledge about the implementation environment of activities that might be planned in the decision, problem-solving ability, availability, initiative and energy, and communications skills. Katzenbach and Smith (1993) delineate these qualities into technical or functional expertise, problem-solving and decisionmaking skills, and interpersonal skills. Represent different thinking or learning styles in the team. The team should blend creative, iterative thinkers with linear, rational analytical thinkers. A team whose members have only an analytical, thing-oriented style will lack creativity and flexibility in problem identification and alternative generation. Different individuals may play different roles. Like cast and crew in a play, there are backers (management, producers, and investors), the director (the deciding officer. team leader, and facilitator), the main players (decision team members), bit players (people who come in for specific functions or roles and leave), and cameo players (high-profile stakeholders or managers who add luster and legitimize to the process and the decision) (Lientz and Rea 1995). Consider an “extended” decision team with “players” from outside the unit or agency, along with the deciding officer and the interdisciplinary team. Possible criteria in choosing specific people include the following: ? Knowledge of divisive controversies or deeply held values ? Representation of viewpoints probably important in the decision ? Responsibility for signing any required documents ? Special needs for geographic scale of decision and the consequences 89 ? ? ? PROCESS Core Question 6 Expertise and experience to address the expected uncertainties and issues Biases and limitations of prospective members Preconceived opinions about the problem or about a proposed action. What special features or constraints will influence how you proceed? Encourage the team to remember similar decisions. Ask members to focus on the process aspects of these decisions and to recollect constraints on the process mapping, problem framing, solution design, and action. Even though the decision will be “political” or “negotiated,” it may still be worth this analysis to help the team negotiate better. The team will better express its own findings and recommendations after completing this analysis. Avoid making the following errors: ? ? Viewing too narrowly what the team can and cannot do, or putting imaginary constraints on the process. Beware of this in teams that are weary of overwhelming schedules or of being whipsawed by political forces or fickle administrative directions. Basing constraints on unexamined fears, such as expecting stakeholder involvement to be complex and confounding or appeals and litigation on the decision to be inevitable. Check the facts. The team may want to discuss how to work within or to ‘flex” the organizational culture to open up process opportunities. Culture is comprised of norms that prescribe how members will operate and get work done. Recurrent, predictable patterns of behavior are preferred ways of coping with complexity, surprise, deception, and ambiguity. Cultural norms, or ground rules, may be unwritten or unstated, but they are the basis of habit and sacred beliefs. Culture can vary with organizational unit. Culture consists of rules, which are written policies and unwritten learning methods (heuristics), habits, traditions, taboos, symbols and artifacts, stories, philosophies, and theories. Clarifying the constraints or preferences created by the organizational culture can help the team decide which of the following adjectives should apply to their decisionmaking process: ? Driven by policy (top down) or broad-scale involvement (bottom up) ? Open or closed to participation in certain cycles ? Linear or iterative in sequence ? Rigorous or flexible ? Comprehensive and systematic or rapid and approximate ? Focused on problem framing or analysis ?? ._ PROCESS Core Question 8 T ’ P 0’ @ ? Directed at optimal solutions or satisfactory solutions ? Directed at efficiency or at fairness in the process. How do you plan to proceed through this decision? Use the Protocol structure as a basic anatomy to design your team’s process. Elements include problem framing, action design, consequence analysis, and action (choice and commitment) stages. Use the Protocol questions to develop tasks, set timelines, and plan different types of involvement. List the tasks and outline a simple timeline with milestones and responsibilities. The timeline can consist of “who,” “what” (task and goal), “how,” and other important elements. Try a schedule that balances team meetings with work time for independent information gathering and analysis. Build in enough time for team members to interact and build interdisciplinary problem-solving ability. Consider carefully the costs and benefits of the analysis and deliberation. Outlays include expertise. time, information collection, and meetings. These can be viewed as investments whose returns include less delay, fewer repeat analyses, fewer appeals and litigation, and greater success in court. But you can spend too much time analyzing. Remember that there are alternative uses of the team’s time and effort. Consider similar situations that have been analyzed or decided lately. Evaluate the decision team’s process, using an easel sheet with “Positive” (good) and “Change” columns. Circle those elements from each column that best apply to the current process design. Or you can use the audit questions in each cycle of the Protocol and write out improvements in the current design. PROBLEM Cycle (Note: There are no tips or took for PROBLEM Core QLE&.O~S l-5, 9-l 1, and 13-l 6.) PROBLEM Core Question 6 What problems or opportunities should be addressed with a new or revised management action? To help the team (or stakeholders) define the problems, ask them to try one or more of the following: ? . Use a round robin to develop independent statements of the problem and display these on a tlip chart. Ask for anonymous statements written on note cards if that seems appropriate. Describe the best, worst, and most probable consequences of not solving the problem. Describe whose problem is being solved by the proposal. State the problem or opportunity as a question. 91 State the problem as given to the group: then ask the individuals for the problem as they understand it. Write out a preliminary statement of the problem: “lasso” key words with a flip-chart marker and ask for elaboration. F ., State what the problem is . . . and what the problem is not. Draw a “mind map” (a network of cause-effect relationships) of the key factors and how they interrelate. Pick out the problem from the mind map. Use a journalistic approach. Put the problem in terms of who, what, when, where, why, and how. Reconstruct the problem by stating its smaller subproblems and weaving them into a larger picture. Or start with a general, abstract, or ambiguous statement of the problem and break it down into smaller subproblems. Use a force-field analysis: List the forces that are worsening or sustaining an unwanted situation or restraining a goal: list those that are decreasing the problem (sustaining the goal). State the problem in terms of these forces (Doyle and Straus 1982). Set up a dialectical inquiry debate. Develop a “straw man” problem statement. Assign one person or group to defend a problem statement, another to present an alternative statement. Each group lists their assumptions about the situation and attacks the other team’s assumptions in a structured debate. A third group evaluates the results of the debate and synthesizes a compromise or integrated problem statement (Evans 199 1). State the problem in the terms of another discipline or subject area (for example, a sociological instead of a biological problem). This technique is called lateral thinking (deBono 1994 ). Think about analogies to the problem. “This problem is like a .” Use the insight to re examine your definition. This is called synectics (Doyle and Straus 1982). Use a new metaphor to describe the way the team should look at the problem. Like a sports team? Like a surgical team? Like an assembly-line team? Would another type of team see this problem differently (Russo and Schoemaker 1989)? PROBLEM Core Question 7 1 ’ P 0’ @ What different perspectives of this problem or opportunity are held by different stakeholders? Different stakeholders have different views about what the problems or opportunities are. Try to understand the widest possible range of problem perspectives so you can anticipate reactions and weave stakeholder needs into the design. Learn these perspectives by facilitating a representative group of stakeholders and interviewing them individually. Simulate 92 ... stakeholder elicitations in the decision team, perhaps with team members playing the roles of different stakeholders. PROBLEM Core Question 8 What is the cause of this problem or opportunity? These are the steps for one type of cause-effect analysis: 1. Identify major factors. Concentrate on dynamic factors such as activities or events that rise and fall and are likely to cause changes. 2. Identify cause-effect relationships. Describe the causal links between factors in a two-column cause-effect table. Causal factors go in the left column, affected factors go in the right column. Factors from the affected column can also be entered in the causal column, if they in turn influence some other factor. For example: Activity Y affects Component A, which in turn affects Component B. 3. Describe the causal relationships as direct or inverse. If the affected factor increases (or decreases) as the causal factor increases (or decreases), the relationship is direct. If the affected factor decreases (or increases) as the causal factor increases (or decreases), the relationship is inverse. For example, an increase in Activity Y causes the measure Component A to increase (a direct relationship). The increase in Component A in turn causes Component B’s value to decrease (an inverse relationship). 4. Diagram the relationships. Use a mind map, which is a network of cause-effect relationships or cause-effect diagram. As the name implies, it maps out how the team or expert believes the system works. The map can be a network of circles (components or attributes), boxes (activities) connected by arrows (indicating influencing processes), with the arrows designated as direct or inverse. Multiple arrows may emanate from or lead into an activity or component. A path is a series of causal connections for a change in an attribute: any change may have multiple pathways. 5. Analyze the relationships as an integrated system. Usually some paths are clearly more influential than others. Follow through the diagram with some simulated changes in key factors that were most mentioned in the problem prospecting. In solving a problem, you may want to look for or design activities in paths that are most influential. In avoiding adverse effects, you may consider an activity on a minor path to be of relatively minor concern. Assessing the relative strengths of these pathways is mostly a matter of expert judgment. PROBLEM Core Question 12 T ’ P 0’ @ Is there a need for action to resolve this problem? The need describes why any action should be taken. It does not describe what or how it will be done. Need identification can suffer from errors of omission and commission. For example, there are consequences from not identifying a need and not doing anything about it. Similarly, by identifying a need that really does not exist, there will be the unnecessary costs of 93 ’ planning and implementing an action. Ask the team to imagine the consequences of these two types of errors. DESIGN Cycle (Note: There are no tips or tools for DESIGN Core Questions l-3 and 5-l 4.) DESIGN Core Question 4 What activities will accomplish specific objectives? Have the team brainstorm to explore many possible activities. Describe ideal activities that would address each of the objectives. What alternative activities would be better at accomplishing the objectives? Address their consequences, public issues, and perspectives. How many ways are there of improving the proposed activities? Start with the objective that is least satisfied by the proposal. Review the cause-effect chains in the PROBLEM Cycle. How might you intervene in any of these pathways with a new activity? What activities might a fresh team propose if they saw the information you have developed so far’? (You could pose this question to a focus group of stakeholders or another decision team.) List barriers that would keep activities from being considered. Include barriers such as political risk, status-quo inertia, organizational taboos, legal caveats, and traditional norms. Are these barriers serious enough to block good ideas for action? Purge the barriers or chart ways around or through them, then brainstorm activities under the new conditions. CONSEQUENCES Cycle (Note: There CONSEQUENCES Core Question 1 What information is available to help characterize and predict consequences? 1 ’ P 4D 0’ are no tips or tools for CONSEQUENCES Core Questions 3-6 and lo-l 1.) Your team should consider how much and what kinds of information it really needs. Information is always imperfect. Not all information is of the same value to the decision process, but all information has a cost. Question your sources of information. Be sure it is of the highest quality for the cost and makes a difference. Refer to the causal diagrams. Zero in on pivotal missing information. Ask the team, including the deciding officer, to describe what they would need to be 100 percent confident. Expect differences among individuals on the team. For example, there may not be enough information about the alternatives for the deciding officer. The deciding oMcer may want more and different information as the actual choice approaches and the tradeoffs become more visible and acute. The analysts on the team may want to protect their reputations by displaying a large quantity of information in the supporting documentation, even information that is not key in showing 94 differences among the alternatives. New members may be more unsure than more experienced hands and require more information. ‘Ry to answer the following questions about information gathering: Where would new information give different values for explanatory variables? How would it change the values they predicted for the consequences of the proposed actions? Which of the pieces of information would create the largest changes in the predicted values for the cost invested in them? If the new information would not make a difference, why is it needed? Ask for evidence of over- or underestimation of information needs in past experiences. How have team members handled similar questions in the past and what were the outcomes? What lessons did they learn? Ask the team whether there are any better ways to get the same information. Are there possible sources that would be less perfect but cheaper’? Could they adjust the activities after some actions have been taken? This would be the beginning of an adaptive response strategy. CONSEQUENCES Core Question 2 t ’ P 0’ @ How certain (confident) are you that this information is a good basis for accurately predicting consequences? Beware of overconfidence bias. Many people will say they are completely co&dent in their prediction, but their predictions in fact are far off the mark. The team should be able to predict the measure and explain how they made the prediction. Ask members to describe what their level of confidence or certainty means. Why are they comfortable or uncomfortable with the information? As a check on judgment, generate information that tries to disconfhm their predictfons. If the expert “falls apart” or become defensive, he or she may not be as comfortable with the prediction as he or she thought. CONSEQUENCES Core Question 7 What are acceptable consequences on these measures? This part of the Decision protocol is meant to help prioritize refinement efforts. The results do not imply that one attribute or consequence (change in a measure) is more important than another. Remind the team to put acceptable limits on the values of measures, not On levels of activities. Setting limits on measures before they predict the effects of the alternatives helps them avoid biasing the prediction with preconceived notions about the activities. 95 Acceptability is an expression of “how safe is safe enough” (Derby and Keeney 1981, Fischhoff et al. 1981). It is influenced by social, political, and personal values as well as biological and physical realities. Acceptable levels do not necessarily make all stakeholders happy. Some team members and stakeholders will opine that for some measures only zero or near-zero levels are acceptable. This very risk-averse or conservative posture is based on the belief that large uncertainties and possibly irreversible consequences need to be minimized. Other members may be relatively more risk-neutral or even risk-taking. Acceptable limits apply to minimum aZZowa.bZe as well as desired levels. Ask the team to think why these levels were chosen. ? ? What would be the consequences or falling on either side of this level? How conservative is this level? Were the team members or the policymakers too risk averse in setting acceptability at this value? If the team wants to revise the level of acceptability, document why they do. Disagreement about acceptable levels may be high. Determine if differences among the extremes of opinion of the opposing experts or stakeholders would intersect with where predicted values might fall. The team may not have to worry about the disagreements if the predicted values satisfy all competing levels. Ask the team to build an consequence “instrument panel,” analogous to an automobile dashboard panel that informs you whether vital processes in your auto are within acceptable ranges. Under this analogy, you imagine a display of instruments, each describing a global range, an acceptable range, and a range created by the activity. Follow these instructions: I 1. For each measure, establish a global range from the lowest to the highest (worst to best?) possible values. 2. For each global range, establish an acceptable range. This range will reflect the team’s judgment about the thresholds. The width of the acceptable range indicates the range of tolerance for the measure. ” 3 . Estimate the range of values (consequences) that will be expected to result from the alternative. Establish this range as a confidence interval within which you would be accurate, for example, 95% of the time. 4 . Estimate the extreme (worst and best) consequences of the range first, followed by the most likely outcome. Think about the state of information about the measure and the alternative. Extend your range if the natural variability is great or if you are highly uncertain about the consequences. 96 .,-. CONSEQUENCES Core Question 8 What are the cause-effect relationships between the consequence measures, the activities, and other influences? Many, if not most, of the causal descriptions will have been started in PROBLEM Core Question 8. CONSEQUENCES Core Question 8 expands the range of measures and asks for more detailed description of the linkages to not only the objectives measures but also any measures of consequences not accounted for in the objectives (so-called side effects). Get people thinking. Draw out relationships on the blackboard or easel to create a lively interchange. Some may be reluctant to commit to a display if they feel they know too little. Emphasize that the inexactness they feel should be identified in these diagrams. Start by drawing familiar “cycles” such as fire, soil, water, insect or disease, human demographic, and other systems. Challenge the team to bring these cycles together in an integrated scheme, showing where they intersect to cause consequences. It may be difficult to capture everything that is being discussed so have the team review each of the components and influence “arrows” to explain how X influences Y. Encourage debate. Ask one person or subgroup to trace through the causal relationships with one explanation: ask another to offer an alternative trace. Let them debate and provide scenarios in which both explanations could be true and important. Post the causal diagram at each of the team’s sessions. Refer to it frequently. Use it to direct questions and as a map to help sort out confusing situations One approach to specifying interactions is to build an interactions chart: 1. List activities across the top of a flip chart page. 2 . List measures or attributes across the bottom. 3 . Connect the activities to the measures for which there are possible consequences. 4 . Designate for each activity-measure link the direction of the effectpositive (+) or negative (-1. 5 . Designate what the portion of the total effect on a single measure would come from each activity-to-measure arrow. For example the negative effect of a set of activities on fish habitat may come from salvage (-4O%), roading @lo%), and prescribed burning (-20%) for a certain estimated consequence of a reduction in 10 units of habitat. However, there may be a compensating influence by reforestation (+90%) for a net interactive effect of about -10 units. Alternatively. try one of the more structured approaches for describing causal patterns. These include “if-then” rulebases, influence diagraming, and Bayesian belief networks (Schachter. 1986 and 1987; soft systems 97 diagrams (Checkland 1981); system cycles diagrams (Senge 1990); fault and event trees (Sundararajan 199 1); probabilistic scenario modeling (Russo and Schoemaker 1989); and scenario planning techniques (Wack 1985, Geus 1988). CONSEQUENCES Core Question 9 How will the values of the measures change if the alternative action is implemented? This is where the specialists or outside experts may have to rely on their subjective judgment, models, extrapolations, or other sources of information to make their predictions. Ask the team or the appropriate specialists to express predictions as ranges of values, discrete outcomes, or even scenarios. Assign likelihoods to different values to capture their level of uncertainty. Capturing the expert’s thinking while he or she is making the predictions is important. Refer the expert to the cause-effect relationships and have him/her “think aloud,” tracing a path through the diagram. Help the experts break the judgment down into component events that are more frequent and more easily predicted than the compound event. One method of eliciting expert judgment is the expert panel. Group interaction provides feedback and learning and the opportunity to average out compensating biases. The downside of panel prediction is the potential for groupthink-the tendency for group members to agree because they want to be cooperative or fear reprisals (Janis 1972). Panels of the same discipline can be very prone to “groupthink.” Facilitation that encourages candid questioning can help avoid group biases. Individual predictions, especially those organized to elicit the degree of uncertainty in an experts knowledge, can be aggregated to obtain averages that can be weighted by factors such as years of experience and performance in similar judgment tasks. Manage panel assessments to take advantage of the wide range of knowledge and experience. Assemble panels to compensate for the biases of some experts with the contrasting biases of others. Direct intrapanel communication at an exchange of insights rather than pushing toward a consensus of views. Guidelines for organizing and eliciting expert opinion include the following: ? ? , _ Be patient and impartial: understand the decision thoroughly but do not advocate any alternatives. Create an environment where the experts can focus on the task. Remove distractions and influences that could bias the experts’ thinking. Relieve fears. Less experienced team members may be reluctant to exercise their professional judgment. It is acceptable to be completely uncertain about any prediction. 98 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Define the measure or scale to be predicted as specifically as possible. Involve experts in the defhrition process. Experts should agree on the definition and be able to describe the element in their own words and examples. Check for completeness and clarity in outcome definition. You may require each expert to provide his or her degree of certainty for each estimate. This can be expressed as a range of values or as some numerical or verbal expression of his or her confidence in the estimate. For example, an expert could predict the number of trees per acre lost in a severe epidemic as + or -10 trees at 90 percent confidence. Don’t discourage experts from expressing high levels of uncertainty. A wide range in their predictions is useful piece of knowledge that should be considered in the decision process. Low levels of confidence (wide range) are not necessarily bad in that they might reflect a true lack of predictability. Conversely, a high level of confidence (narrow range) is not necessarily good, since many people can be overconfident without being accurate. Don’t waste the experts’ time and efforts. Assess only the measures that are most important to the decision. Isolate these critical elements by sensitivity testing the causal models before beginning the assessment process. Encourage experts to explain their rationale and to consider extremely likely and unlikely outcomes. Ask for estimates of extremely unlikely outcomes first and then obtain estimates for more likely outcomes. People tend to anchor on initial estimates unless they are assisted in recognizing the true variability in outcomes. Check experts against any data that might be available about similar measures or events. Ask experts to reconcile differences between their assessments and historical records. Present extreme outcomes, asking experts already occurred and to explain why. Pay are sequenced. People often overestimate following extreme outcomes because they is for the next observation to be closer to to imagine that they have attention to how outcomes or underestimate values forget the normal pattern the average. Watch for the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of several values occurring together. For example, the conjunction of a bad fire season, an insect outbreak, personnel shortages, and a budget shortfall may appear to be a vivid and plausible scenario, but the likelihood of all these events occurring together is quite small. Scientists who have been trained to look for connections among elements in ecological or economic systems can sometimes mistake largely random coincidences for patterns. Listen for words such as “inevitable,” “ultimately,” “should have (known) ,” and “looking back.” These are clues of hindsight bias in 99 judgment. Be ready to produce contrary evidence, scenarios, and data that disagree with past experiences and challenge preliminary judgments. ? 1’ .e. Bare events are hard to assess because there are little to no data about their occurrence and human experts have little experience with them. Judgment is difficult because it calls for distinctions among very small probabilities. There are several techniques for decomposing rare event scenarios into sets of subevents. The probability of the subevents and sequences are multiplied to get an overall likelihood of the event occurring. More information on assessment processes for subjective judgments is described in Merkhofer (1987), Myer and Booker (199 l), Spetzler and Stael Von Holstein (1975), and Cleaves (1994). ACTION Cycle (Note: There are no tips or tools for ACTION Core Questions 2-l 0 and 12-l 7.) ACTION Core Question 1 How do the alternatives compare in meeting the objectives and minimizing negative consequences? There are many ways of comparing and choosing the best alternative. One of the most difficult issues in making these comparisons is dealing with multiple consequences in different measures. Converting measure values to some common scale can be helpful if the team can agree on the scaling process and is able to explain it to the deciding offricers and stakeholders who must use the comparisons. .r One way is to scale each of the possible values for a measure from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Each alternative then is “scored” or rated on this common measure. With these numbers, the team and the deciding officer has several options: . Set minimum limits (0 to 100) for acceptability, below which you screen out the alternative from further consideration. Eliminate those alternatives that do not satisfy some minimum level on each measure. The remaining alternatives can be compared with more complex techniques (below). Hank the alternatives for each measure and choose the alternative that ranks highest on the largest number of objectives or consequence measures. This assumes that all the objectives or measures are equally important. . . . ,, Bank the objectives or measures and choose the alternative that best meets the most important objectives. Weight the measures themselves from least (0) to most important (1). Develop a weighted total score. For example, the weight of measure A (.70) times the score of Alternative X on that measure (50). The score in this example would be .70 x .50 = .35. Develop scores for all measures and alternatives. Bank the alternatives with the highest total weighted score. 100 - ? ACTION Core Question 11 Calculate the advantage with those of the worst alternative that has the tage score (greatest net of each alternative by comparing its score alternative for each measure. Choose the most advantages or the highest total advanadvantage). What must be done to ensure that the action will be implemented? Successful implementation involves handling many barriers. Any action plan should develop answers to the following questions: ? Are resources adequate? ? Do others have the motivation and commitment needed7 ? Is the idea likely to meet with general resistance to change? ? Are there procedural obstacles? ? Are there structural obstacles? ? What organizational and managerial policies need to be changed? ? How much risk-taking is required? ? Are there any power struggles that might block implementation? ? Are there interpersonal conflicts that might retard progress? ? Is the general organizational climate one of distrust or trust?