“Can immigration constitute a sensible solution to Final Report

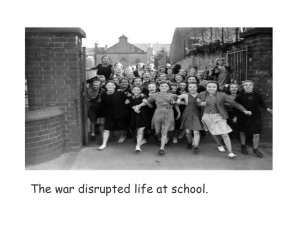

advertisement