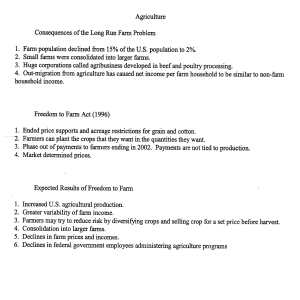

E.A.

advertisement