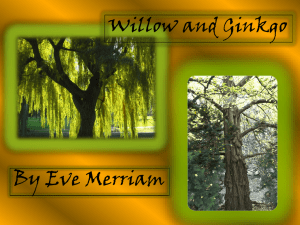

Willow response to changing climate on Yellowstone’s Northern Winter Range

advertisement

Willow response to changing climate on Yellowstone’s Northern Winter Range Introduction Beginning about 1998 willows that had been surpressed by elk browsing for more than 50 years on Yellowstone National Park’s northern winter range began to grow tall in some places. This presentation explores the possibility that climate change could be the cause. Willow patch near Blacktail Deer Cr. with released and suppressed willows. Note well browsed willow in foreground including many broken branches and broken willow clump at the left side of the larger clumps. Branches on the edge of the tall clumps are also browsed. Hedged willow height and height at end of winter 1998-99 (0.50-0.60 m) is indicated for a large patch on the edge of a ca. 2 ha stand of willows. Note old elk tracks in foreground and feeding craters behind and to the right of the clump. Willows grew about a meter during the summer of 1999 then were browsed to this height during the winter of 1999-2000 (ca 1.30 m) Stems were unbrowsed in winter of 2000-01 and grew only 0.2-0.4 m. Height of willows at beginning of winter of 2001- 2002, (2.3-2.4 m). Clump inside large stand. Note feeding crater and numerous elk tracks and an elk bed behind and to right of willow clump. Hedged height at end of winter 1998-99 (0.50-0.60 m). Clump inside large stand. Height of willows after browsing of winter of 1999-2000 (ca 1.30 m) Clump inside large stand. Height of willows at beginning of winter of 2001- 2002, (2.3-2.4 m). Stems were unbrowsed in winter of 2000-01 and grew only 0.2-0.4 m. Two unusual things happened to produce tall willows. • Phenomenal growth • Effectively defended against large herbivores Why?? Could it be climatically induced? Willow Physiology Growth: • Depends on carbohydrates available and is regulated by plant hormones (auxins) produced in buds and expanding leaves • Auxin must be transported to sites of growth in stems Could change in precipitation be the cause? Water relations affect growth through stomatal control that regulates the availability of CO2 for photosynthesis. Willows grow in wet places and generally have enough available water to keep stomata open during the day all season as shown in the next slide. Seasonal Water Relations S. wolfii S. planifolia Betula Taken from Young et al. (1985) Precipitation is not significantly different before and after the change in growth habit Precipitation at Northeast Entrance Water Yr May-Aug Inches 40 30 20 10 0 1985 1990 1995 Year 2000 2005 Could change in temperature be the cause? Rates of growth during control conditions (20ºC) and lowtemperature (10ºC) treatments show strong climate affect Rate of growth in length (mm mm/ day -1) Experiment 1 Control First day Final day (30) % (of control) Hordeum 1.92 ± 0.10 0.32 ± 0.03 0.75 ± 0.04 44a Phalaris 1.22 ± 0.06 0.21 ± 0.06 0.13 ± 0.03 11b Festuca 0.09 ± 0.02 0.00 ± 0.02 0.01 ± 0.00 9b Betula 0.74 ± 0.07 0.04 ± 0.04 0.19 ± 0.03 28c Salix 1.05 ± 0.07 0.09 ± 0.03 0.14 ± 0.03 15c Taken from Hjelm and Ögren (2003) Photosynthetic cold acclimation of fully developed leaves allows for carbohydrate production in willows transferred from 20ºC to 10ºC. Taken from Hjelm and Ögren (2003) Fig. 4. (A) Aspen trees subjected to short-day treatment in a climate chamber Schrader, J. et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10096-10101 Copyright ©2003 by the National Academy of Sciences Auxin Levels after transfer from long to short days Taken from Olsen et al. (1995) Willow Physiology Defensive Chemicals: • Depend on available carbohydrates • Occur only after growth needs are satisfied Glycoside content in the bark of Salix alba vs. month Taken from Thieme (1965) Glycoside content in the bark of Salix purpurea vs. month Taken from Thieme (1965) Glycoside content in the bark of Salix cinerea vs. month Taken from Thieme (1965) Willow Physiology Summary • Temperature has a definite affect on carbohydrate production • Willows are adapted to cooler temperatures. • Auxin production and transport is temperature and day-length sensitive • Defensive chemicals are produced during cold period of the year Effects of Climatic Change Day length control means that growth occurs during early half of warm season leaving carbohydrates produced during last half available for storage, defensive chemical production and other processes. • Longer periods of favorable conditions in the spring provide longer stems • Longer periods of favorable conditions in the fall provide more defensive chemicals Total degree-days (May-Oct) measured at Northeast Entrance do not indicate that atmospheric heat was different before and after the change in growth habit Degree-Days Total Degree Days 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1985 1990 1995 Year 2000 2005 Total days (May-Oct) with minimum temperature greater than freezing at Northeast Entrance increased 25 days (29%) May-Oct 130 120 Days 110 100 90 80 70 60 1985 1990 1995 Year 2000 2005 Early season days with minimum temperature greater than freezing at Northeast Entrance increased 12 days (23%) May-Jul 75 70 Days 65 60 55 50 45 40 1985 1990 1995 Year 2000 2005 Late season days with minimum temperature greater than freezing at Northeast Entrance increased 14 days (37%) Days Aug-Oct 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 1985 1990 1995 Year 2000 2005 Variation in Willow Response in a Small Area could be caused by variation in genetic factors and microsite conditions Conclusion Willow physiology indicates that the increase in days with minimum temperature greater than 0ºC could explain the recent change in willow growth habit. Literature cited: Hjelm U, Oegren E. 2003. Is photosynthetic acclimation to low temperature controlled by capacities for storage and growth at low temperatures? Results from comparative studies of grasses and trees. Physiologia Plantarum 119113-20. Schrader J, Baba K, May ST, Palme K, Bennett M, Bhalerao RP, Sandberg G. 2003. Polar auxin transport in the wood-forming tissues of hybrid aspen is under simultaneous control of developmental and environmental signals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 100(17)10096-101. Thieme H. 1965. Die Phenologlycoside der Salicaceen, 6 Mitteilung Untersuchen ueber die Jahrzeitlich Veraenderungen der Glycosidkonzentrationen, ueber die Abhangigkeit des Glycosidegehalts von der Tageszeit und vom Alter Pflanzenorgane. Pharmazie 20688-91. Young DR, Burke IC, Knight DH. 1985. Water Relations of High-elevation Phreatophytes in Wyoming. American Midland Naturalist 114(2)384-92.