Rights of Public Access to the Foreshore: and Opinions

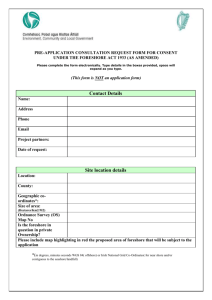

advertisement