Math 2250 Written HW #12 Solutions

advertisement

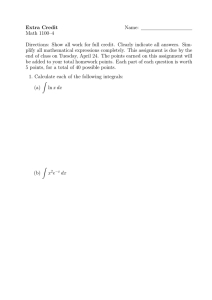

Math 2250 Written HW #12 Solutions 1. A large international jet (like a Boeing 747 or an Airbus A340) typically has a takeoff speed at sea level of about 80 m/s (which is approximately 180 mph), and needs to get up to that speed within the 3000 meters of a typical international runway. Assuming the engines provide a constant acceleration and the plane starts from rest, what’s the minimum acceleration needed to ensure the plane will take off? Answer: Let s(t) be the position of the plane on the runway t seconds after it starts accelerating down the runway. Let v(t) = s0 (t) be the plane’s velocity at time t, and let a(t) = v 0 (t) = s00 (t) be the acceleration. Then we know that a(t) = A for some constant A which we’re trying to figure out. Moreover, we know that the plane starts at one end of the runway, so s(0) = 0, and that it starts from rest, so v(0) = 0. Now, since v 0 (t) = a(t) = A, we just have to find some function with derivative A and we’ll d know that v(t) differs from that function by a constant. Clearly, dt (At) = A, so we know that v(t) = At + C for some constant C. Now, since v(0) = 0, we know that 0 = A(0) + C = C, so in fact v(t) = At. In turn, since s0 (t) = v(t) and s(t) = d dt A 2 2t = At, this means that A 2 t +D 2 for some constant D. Since s(0) = 0, we see that 0= so D = 0 and we have that s(t) = A 2 (0) + D = D, 2 A 2 2t . Of course, we still need to figure out what A is. To do that, we need to use the fact that the plane should be going 80 m/s when it is 3000 meters down the runway. In other words, if we call the time when the plane reaches the end of the runway t0 , we should have that s(t0 ) = 3000 and v(t0 ) = 80. In other words, A 2 t 2 0 80 = At0 , 3000 = 1 so we see that t0 = so A = 3200 3000 = 80 A. Plugging that into the first equation yields A 80 2 3000 = 2 A A 6400 3000 = · 2 2 A 3200 , 3000 = A 16 15 . Therefore, the plane’s acceleration needs to be at least 2. Evaluate the limit 16 15 m/s2 to ensure takeoff. 1 x lim 1+ . x→+∞ x (Although you derived this as a consequence, some people treat this as the definition of this number.) Answer: As x → +∞, the expression 1 + x1 converges to 1, so we have an expression in the ∞ . To deal with this, let’s take the natural logarithm: ln 1 + 1 x = indeterminate form 1 x x ln 1 + x1 , which is now in the form ∞ · 0. To deal with that, we can re-write as ln 1 + x1 1 = x ln 1 + . x 1/x Therefore, ln 1 + x1 1 x lim ln 1+ = lim , x→+∞ x→+∞ x 1/x which is now in a form which we can evaluate using L’Hôpital’s Rule. Since d 1 1 −1 −1 ln 1 + = 1 · x2 = x2 + x dx x 1+ x and d 1 −1 = 2, dx x x L’Hôpital’s Rule tells us that lim ln x→+∞ 1 1+ x x ln 1 + = lim x→+∞ 1/x = 1 x −1 x2 +x lim x→+∞ −1 x2 x2 = lim x2 + x x2 1/x2 · = lim 2 x→+∞ x + x 1/x2 1 = lim x→+∞ 1 + 1/x = 1. x→+∞ 2 So we’ve seen that lim ln x→+∞ meaning that 1 1+ x x = 1, 1 x = e1 = e. 1+ x→+∞ x lim 3. Use your knowledge of calculus to draw the graph of the function f (x) = x2 ex . In particular, be sure to label any inflection points, local maxima, and local minima, and if the function has an absolute minimum and/or an absolute maximum, find them. Answer: First, we check for asymptotes. The function is defined everywhere, so there are no vertical asymptotes. As for horizontal asymptotes, lim x2 ex = +∞, x→+∞ since both x2 and ex go to +∞. On the other hand, lim x2 ex x→−∞ is in the form ∞ · 0 since limx→−∞ ex = 0. Therefore, we can re-write in using L’Hôpital’s Rule: ∞ ∞ form and evaluate x2 x→−∞ 1/ex x2 = lim −x x→−∞ e d 2 dx x = lim d −x x→−∞ dx (e ) 2x = lim . x→−∞ −e−x lim x2 ex = lim x→−∞ Notice that this is still in the form ∞ ∞, so we apply L’Hôpital’s Rule again: 2x = lim x→−∞ x→−∞ −e−x lim = lim d dx (2x) d −x dx (−e ) 2 x→−∞ e−x =0 since the denominator goes to +∞. Therefore, the function has a horizontal asymptote at y = 0. Now, to look for critical points, we evaluate f 0 (x) = 2xex + x2 ex = xex (2 + x), which is defined everywhere, so the critical points occur when f 0 (x) = 0, meaning that either x = 0 or x = −2. The derivative is positive and negative on the regions shown: 3 + - + -2 0 which we can check by evaluating 3 >0 e3 −1 <0 = e f 0 (−3) = −3e−3 (2 + (−3)) = 3e−3 = f 0 (−1) = −1e−1 (2 + (−1)) = −e−1 f 0 (1) = 1e1 (2 + 1) = 3e > 0 This shows that f (x) is increasing on (−∞, −2) and (0, +∞) and f (x) is decreasing on (−2, 0). Therefore, f (x) has a local maximum at (−2, f (−2)) = −2, e42 and a local minimum at (0, f (0)) = (0, 0). Since f (x) shoots off to +∞ as x → +∞, we know that the local maximum can’t be an absolute maximum. On the other hand, since f (x) is increasing on (−∞, −2) and approaches 0 as x → −∞, we see that f (x) can never get smaller than 0, so the point (0, 0) is actually the absolute minimum of the function. Finally, we can compute the second derivative: d (xex (2 + x)) dx d d = (xex ) (2 + x) + xex (2 + x) dx dx = (1 · ex + xex ) (2 + x) + xex (1) f 00 (x) = = 2ex + xex + 2xex + x2 ex + xex = ex (x2 + 4x + 2). Therefore, the possible inflection points are when f 00 (x) = 0, meaning when x2 + 4x + 2 = 0, which happens when p √ √ √ −4 ± 42 − 4(1)(2) −4 ± 16 − 8 −4 ± 2 2 x= = = = −2 ± 2. 2(1) 2 2 Therefore, the second derivative is positive and negative on the regions show: + -2 - + -2+ 2 2 which we can check by evaluating 2 >0 e4 −1 f 00 (−1) = e−1 ((−1)2 + 4(−1) + 2) = <0 e f 00 (0) = e0 (02 + 4(0) + 2) = 2 > 0. f 00 (−4) = e−4 ((−4)2 + 4(−4) + 2) = 4 √ √ Therefore, the function is concave up on −∞, −2 − 2 and −2 + 2, +∞ and concave √ √ down on −2 − 2, −2 + 2 , meaning that the inflection points are √ 2 −2−√2 √ √ 2 −2+√2 √ and −2 + 2, −2 + 2 e . −2 − 2, −2 − 2 e Putting this all together yields the graph of the function: 2 -2, J-2 - 2 , I-2 - 2 -2- 2 2M ã N 4 ã2 1 O æ à J-2+ 2 , H-2+ 2 L2 ã-2+ 2 N à æ -2 - -2 2 5 -2+ 2 H0, 0L