Producing Material Culture for Global Markets:

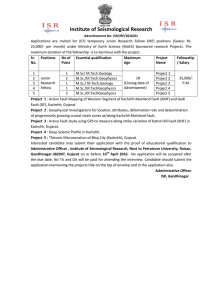

advertisement

1 Producing Material Culture for Global Markets: The Craft Economy of Eighteenth and Twenty-first Century India Introduction Manufacturing is once more on the world stage as we have watched the numbers of the dead in Bangaladesh’s recent textile factory disaster mount to nearly 1000. Today a global story of industry and manufacturing presents us on the one hand with China’s huge factory regions where whole cities manufacture buttons or zips, or with unregulated clothing factories such as Bangaladesh’s, feeding the cheap clothing consumer cultures of the West. When I wrote my first book, The Machinery Question – manufacture was perceived as a history of factories and machinery,. Its depiction in the early nineteenth century was not so different, but included the role of sweated labour. Cruikshank’s ‘A Tremendous Sacrifice’ showed cheap female labour being ground up in a mill, while women in shopping emporia not so far away declared ‘I don’t know how they can possibly make them so cheap’. What went before this factory labour was assumed to be craft and artisan manufacture with some household domestic industry. Historians in the 1970s and 1980s debated the rise of the factory system, protoindustrialization and flexible specialization, and other alternatives to mass production. They did so in their separate fields of European history, Asian Studies and Colonial and Imperial History. The rise of globalization from the 1990s demanded we turn to the resurgence of Asia as a manufacturing power house as we watched manufacturing in Europe and the US decline. It also demanded that we rethink our own histories of industrialization – they were not a separate European miracle, but connected to wider world trade and Asian industry. Today I want to discuss craft and other small-scale manufacture not as an art form, but as a part of manufacture and industry. 2 I want to address concepts of craft, artisanship and skill as these have been bound up with cycles of production across the long chronology of India’s history, and especially in the area I discuss today, Gujarat and Kachchh, its northern province. The people in the region today maintain strong craft traditions, but their lives are changing in face of the markets of the new global India. They carry important historical parallels with their forebears of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries who produced for pre-colonial Indian Ocean and colonial world trade. In Mandvi, the celebrated ancient port of Kachchh, best known for its boatbuilding of dhows made from teak and acacia wood, boats that sailed the Arabian Sea to Zanzibar and beyond, we also find a long history of bandhani making. Bandhani, or tie dye, is widely practiced in Bhuj, Mandvi and many other towns and outlying villages across Kachchh. It is a classic outworking occupation. Organized by men, especially in the Khatri community through family networks, these prepare the cloth in workshops where they stencil the designs onto fine cotton or silk. The tying is done mainly by women but also by male outworkers; the fabric is then dyed by men who have passed their knowledge on through generations. Sisters Hanifa and Jamila Khanna and all other members of their family combine tying with agricultural and domestic labour. It takes them 5 days to complete a piece of work and they might earn 1500-1800 Rs. per month. The work for them and for all the women who practice it is also like a habit; they never sit empty-handed. In a small darkened house across from the putting out shop where they bring their goods, Neelam Khanna counts the tied bandh. She is well-educated with a second year of a BComm, but unmarried and the carer for her mother after the death of her father. She is widely trusted by contractors and workers, and with steady work; she earns 3,000 Rs. a month. The counting is intricate, but logical – she takes 15 minutes to count 1,000 kadi (or chains of 4 ties each). Their stories are part of an oral history project I have led and conducted among the craftspeople of Kutch. The work, the organization of production and the challenges of local and world markets revealed in these interviews has given me insight into past frameworks of industry in the area, and into the survival of small scale production in face of the large economic shifts of globalization. 3 . Craft and Small Scale Production: Historical Frameworks Craft and small scale production in India today needs to be placed in its historical context, and in the context of the ways historians have written about industrialization. Few now study manufacture, but it is central to the themes of material culture and consumption that inspire us today. Early historical analysis of industrialization compared a dynamic capitalintensive and mechanized factory sector with unchanging pre-industrial handicrafts. India in particular was seen as embedded in age-old practices that were not part of a changing wider world. The debate on proto-industrialization during the 1980s turned to examine the commercial reorganization of rural manufactures, especially in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europe. Analysis of mixed agricultural and industrial occupations, of the division of labour, and of advanced putting out systems that yielded a surplus for merchant manufacturers appeared to offer a possible path to industrialization. But extensive research on individual regions yielded equal possibilities of paths to sweated industry and eventual industrial decline. Historians of India during this period engaged in a debate over deindustrialization and the colonial control of India’s textile industry. A few, such as Frank Perlin, connected India’s commercial manufacture in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to European developments. He compared manufactures in Bengal and the Coromandel coast to those described by Witold Klima in Bohemia. In both places Dutch and English merchants penetrated textile regions, controlling markets and production networks, and gaining greater supervisory control over spinners and weavers. He showed us how that phase of protoindustrialization was entangled in large-scale inter-regional connections and world commerce. Some of Europe’s and North America’s regions, however, had stronglyembedded nodes of crafts and skills. These yielded many externalities, and such regions seemed for sociologists and historians of the 1980s to offer an alternative historical path to the large factories and mass production which seemed at the time to have had its day; they sought a real possibility of flexible specialization. 4 Debate first centred on the persistence of small firms; they were clearly evidence of ‘industrial dualism’, where craft sectors and small units of production responded to surges of demand or provided the varieties tacked onto main production lines. But, asked Piore, Sabel and Zeitlin, had there once been and indeed was there still a real possibility of a craft alternative to mass production? To answer this question they sought out industrial districts – such as Emilia-Romagna – which appeared to offer an alternative of a dynamic region of many small producers. Their historical enquiries turned to the Lyon silk and hardware industries; to cutlery & specialty steels in Solingen, Remscheid and Sheffield; to calicoes in Alsace, woollens in Roubaix, textiles in Philadelphia. There small scale producers had used multi-purpose machines and skilled labour to make a changing assortment of semi-customised products. Their eventual decline, these historical sociologists argued, was not due to their model of technological development, but to political, institutional and economic factors. The backdrop for these histories was a utopian vision of alternative economic development, based in regions, in co-operative institutions and small in scale. The widespread transfers of industrial production with the onset of globalization swept away the prospects for many of these vaunted European specialist manufacturing regions. We have not, as historians, focussed much on this world of work and of making things during the past three decades since these debates; many turned instead to histories of consumerism. Yet this older historical interest in craft, skill and artisanship has returned to historical agendas more recently in the form of Jan de Vries’s ‘industrious revolution’, in which household connections of production and consumption generated consumer and industrial revolutions. Likewise, the role of technology has re-appeared in debates on the ‘great divergence’ in development paths between Asia and Europe, and in discussions of particular ‘East Asian development paths’. Prasannan Parthasarathi, Tirthankar Roy and David Washbrook have debated the extent and direction of an Indian dynamic culture of technical knowledge. Kaoru Sugihara and other Japanese economic historians have contrasted an East Asian Development path with the West’s capital- and resource-intensive path. A labour-intensive, resource- and energysaving path was part of Japanese and wider Asian economic development. 5 Not just labour, but skills have returned to a central place in discussion of industrialization. Skill and the ‘tacit knowledge‘ underlying it have been central to the concept of ‘useful knowledge’ as developed by Joel Mokyr; likewise ‘local knowledge’ and ‘nodes of craft skill’ were vital to the artisans that the late Larry Epstein followed across Europe as they carried and reconfigured knowledge sets, and brought technological leadership to new regions of early modern Europe. Craft has been a particularly potent political issue in India’s industrial history, and discussion of India’s craft economies today and in the past takes us to the heart of the debates on colonialism and de-industrialization. Recent books by Abigail McGowan, Crafting the Nation in Colonial India (2009) and Douglas Haynes, Small Town Capitalism in Western India (2012) address the political potency of craft in modern India. The artisan became a political symbol of India’s fate under colonialism. For British colonizers the crafts demonstrated India’s economic backwardness, but Europeans also collected India’s unique and beautiful products in museum collections that orientalised not just the goods, but the artisans themselves. In these discourses artisans were traditional, ossified, homogenized, subjects to be archived and preserved in museums and art schools.1 For nationalists craft producers represented the remains of the self-sufficient society that they thought India had once been before the disruption of colonialism, industrialization and the competition of European textiles. Gandhi’s khadi campaign epitomised the turning of these discourses into a craft critique of Empire. These historical perspectives were as utopian as were those of the flexible specialists; in this case the artisan and her craft represented autonomy. The discourses also informed the writing of Indian economic history for the generations after Independence.2 Economic historians of India debated the de-industrialization thesis and the fate of India’s artisans from the later 1960s into the 1980s.3 Comparing the course of artisan production in Gujarat and Kachchh over its early modern global history and its recent framework of globalization thus allows us to engage with these larger debates on industrialization and on India’s industrial history over the pre-colonial, colonial, nationalist and recent global periods. Gujarat, Kachchh and Long-distance Trade I now turn to Gujarat and Kachchh. 6 Kachchh, in a remote area between Northern Gujarat and Sindh, now modern Pakistan, became known in the wider world in the wake of the 2001 earthquake. NGOs converged on the region, and the Indian government developed the area leading north from Ahmedabad into Southern Kachchh as the Kandla Special Economic Zone. Today trucks, cars and camels jostle on a four-lane highway leading past many factory developments. In 1809 Alexander Walker, the British Chief Resident at Baroda travelled through the region and described it as a country whose ‘independence over a series of centuries altho’ situated between powerful and ambitious empires, is a sufficient proof that it has yielded nothing to gratify ambition, or to compensate the expense of conquest.’4 Yet this was the region that produced many of the over 1200 pieces of printed cotton textiles in the Ashmolean’s Newberry Collection, most of these dated between the tenth and fifteenth centuries, and traded to Egypt, up the Red Sea ports through the Middle East, out across the Arabian Sea to East Africa, and down the Malabar coast and on to present-day Indonesia. Its textiles were soon to fill the cargoes of Portuguese, Dutch, then British ships trading from Diu, Mandvi and Surat, and pass on to European consumers. Today it remains a knowledge node of the crafts, its people responding to the challenges and opportunities opened in the wake of the earthquake and globalization. Gujarat was celebrated from an early period for its extensive Indian Ocean trade, especially in the textiles of the region. Surat by the late seventeenth century provided Europe with indigo, printed cloth, quilts and fine Mochi embroideries. The East India Company traded over 20 different fabric types from Surat in 1708 in 53 different colours, patterns and lengths. 5 Recent research emphasises the continued strength of trade at the end of the eighteenth century among the English, other European Companies and many European and Asian private traders. This was also a period of expansion of European trade with the northern part of Gujarat, the region now known as Kachchh. The English East India Company was already well aware of its textiles by 1710, directing its officials in Surat to give special attention to the trade. Mandvi in the mid eighteenth century was a cosmopolitan destination of many Indian Ocean merchants especially interested in cotton and textiles. With the coming of the Dutch in the early eighteenth century these goods entered into the VOC’s extended intra-Asian trade network with markets in Bengal, Malacca and Batavia and China, and also to the Dutch Republic.6 The expansion of trade from the region was led both by the Dutch initiative in the region between 1750 and 1758 as well as by the pro-merchant policies of the rulers of Kachchh and their ‘large degree of independence from British interference in their domestic affairs.’7 7 Well known for its agricultural products of indigo and cotton, and even of rice in the areas close to the Sindh frontier, it lost major sources of irrigation first in the mid-1760s, when the ruler of Sindh blocked a branch of the Indus, and later in the wake of the 1819 earthquake which changed the course of the Indus.8 Yet even in the 1820s the town was a by-word for ethnic diversity and an exotic luxury trade, especially from Africa. James Tod, Political Agent of Rasputan, and later author of Annals and Antiquities of Rajas’han perambulated about the town in 1823, encountering ‘groups of persons from all countries: the swarthy Ethiop, the Hindki of the Caucasus, the dignified Arabian, the bland Hindu banyan, or consequential Gosén, in his orangecoloured robes, half priest, half merchant.’ 9 On the streets he found rhinocerous hides being prepared for shields, elephants’ teeth, dates, almonds and pistachios from the Africa and Arabian Seas trade, but cotton, he noticed, was still the staple trade.10 The crafts developed under the patronage of the royal courts, for long distance trade, and for local ceremonial use. The Kutch dynasty ruled from Bhuj from 1549 until the merger with the Indian Union in 1948, but was marginalised from the later eighteenth century as a princely state under British rule. The city now has a population of 133,500; the earthquake of 2001 killed 13,000 in the city and in the tribal and rural communities in the surrounding region; there has been much rebuilding in the years since.11 The remains of the Aina Mahal palace, which folk history relates was built and decorated by the engineer and architect Ram Singh Malam in the early 1750s under Maharao Lakho, show a significant integration of Dutch and other European arts and crafts. Design and architecture there and in Mandvi reflect the period of expansive commerce in the mid-eighteenth century, the Dutch presence and openness to European arts and crafts.12 Bhuj was also long a ‘knowledge node’ of the crafts including bandhani (silk tie dye), ajrakh (resist cotton printing), embroidery, batik prints, cotton and woollen weaving, lacquerware, enamelling, woodcarving, and silver and gold jewellery work. Local production served the particular demands of the Jat, Ahir, Harijan and Rabari tribes.13 The craftsmen of this remote region also supplied both the sumptuary and ordinary dress of the nomadic cattle herders of Banni in Northern Kachchh, fine fabrics for the court in Bhuj, and merchants trading from Mandvi to Diu and Surat, and from there to markets in Africa, the Middle East, Europe and South East Asia. Many of its craftsmen came from Sindh, groups invited by the king of Kachchh, Rao Baharmalji 1 (1586-1631), including dyers, printers, potters and embroiderers. Skills and design connected further to the Persian Empire.14 8 Eighteenth-Century and Early Nineteenth-Century Accounts of Kachchh and Gujarat British and other European travellers left some accounts of the region, its castes and craftspeople between the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. How was the industry and craft culture of the area between Surat and Kachchh described in the eighteenth century? A remarkable survey of weaving in Surat, The Chief’s Minute to the Commercial Board of the East India Company in 1795, found c. 15,800 looms worked by specific weaving groups. The Chief’s Minute gave a detailed account of the contracting system, and proposals for a new system of direct access to the weavers. It also provided an intensely detailed account of the production process, virtually a census of products, looms and the peoples who worked on each type of cloth. The EIC faced fierce competition from native and Portuguese, French and Dutch private merchants, and could not control the quality of the products it wanted to access.15 Western India was then already of great interest to European investigators. Gujarat was a widely-recognized source of fine cotton and skilled manufacture. Anton Hove, a Polish doctor and naturalist sent in 1787 by Joseph Banks to investigate cotton cultivation in Gujarat, and to collect plants and seeds, also attempted to gather information on manufacture.16 Travelling from Bombay to Surat, he noted exports including fine cotton, indigo, Ahmedabad carpets, silks, kinkobs, Ilachu or satin and cotton cloth and imports of coffee, sugar, spices, and of iron, copper and ivory. Continuing on to Broach, present day Bharuch, he found a place where ‘every street swarms with different casts - Arabs, Moguls, and the many tribes of Gentoos…Their manufacture is of cloth of various kinds, as Bafta, Daria, Czarhany. Bafta is the finest of all, coming near the muslin of Bengal; Czahany and Daria are the striped muslins which the ladies wear in England. Duty comes near the Madras long cloth, and is exported to different parts of India to great advantage.’17 Hove then went on to investigate spinning and weaving in Senapur, present day Sinor, where he could gain no access to report on female spinners, but did find a highly specialized division of labour among the weavers which he recommended to English cotton manufacturers.18 Several Scottish East India Company officers went on to provide more extensive travel and reporting on history and peoples of Gujarat and Kachchh. Alexander Walker (1764-1831) came to India in 1780 as an EIC cadet; he served in Bombay, Malabar and Mysore. He was sent to Gujarat in 1800; he became political resident at Baroda in 1802, and led a campaign into Kutch in 1809. He kept detailed records of local practices, and collected Arabic, Sanskrit and Persian manuscripts.19 Walker wrote an extensive report on the region to 9 his superiors in Bombay in April, 1809. ‘The little principality of Kutch under its own Rajas, could never become a rival to the Company’ but it might either be a useful barrier against the designs of our enemies’..., it might form an Emporium for the transit of the Company’s goods thro’ that Country…20 Some months later on a march through Kachchh Walker advised against full military intervention. Though Walker discounted the military significance of the region and gave little credit to its manufactures, in the years he spent there he gathered materials for a history of Gujarat and notes on the customs, religion and manners of the peoples, and these included material on Kachchh. He put together some of the materials into a two volume manuscript, ‘An Account of Castes and Professions in Guzerat’ in 1823. He described this as compiled from notes of conversations with natives who came to him on business, and included short accounts of crafts including weavers, dyers and printers, gold and silversmiths, ironsmiths, paper makers and stone cutters.21 The Scots who followed him, James McMurdo, and Alexander Forbes wrote even less about the manufactures and artisanal skills of the people. A closer, though still limited account of the towns, customs and crafts of Kachchh was left by Marianna Postans in 1839 in her Cutch or Random Sketches.22 The wife of an army officer, she spent five years in Kachchh. She noted that the principal manufacture of the region was its cotton cloth, ‘woven of various colours, and eminently fanciful designs’.23 Her short chapter on the Workmen of Cutch praised craft abilities of ‘imitation’ and ‘the fame their beautiful work has acquired, both in England, where it is now well known, and also in all parts of India. The diversity of their talents has classed them as brass-founders, embroiderers, armourers, and cunning workmen in gold and silver.’24 Small Scale Industry in Western India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries What happened to these vibrant craft and textile regions with their long histories of global trade as they passed through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Their histories have been those of colonialism and de-industrialization in India more broadly. Indeed Postans already in 1839 put it eloquently for the region of Kutch. The annals of India present, indeed, a dark page in the history of nations. Her commerce, which was once of sufficient importance and magnitude to excite in the Tyrians, Egyptians, and Venetians, a desire for traffic, is now confined to the export of a few natural productions of comparatively 10 little value; and the produce of her far-famed looms once so highly coveted by the rich and the fair, is exchanged for a manufacture of coarse cloths; whilst the raw cotton which her fields produce is sent to England, to be manufactured into a fabric designed for exportation to the Indian market.25 Yet recent studies of the late colonial and nationalist periods have found not just a survival of craft economies, but a resurgence of small producer capitalism in the interstices of colonial constraints and economic underdevelopment. Tirthankar Roy’s study, Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India (1999) focused on the late colonial period, and covered broader areas of India over the period 1870-1930. He found 10-15 million industrial workers in the mid 19th Century, and amongst these were producers known worldwide for their craftsmanship. Increased commercialization after the opening of the Suez Canal fostered more production for non-local markets. In the period since 1947 smallscale industrial production increased its share of waged employment; indeed there was staggering growth in the towns and informal industrial labour in the crafts he studied: handloom weaving, gold thread, brassware, leather, glassware and carpets.26 Roy concluded that artisan industry ‘has not just survived, but shaped the character of industrialization both in colonial and post-colonial India.’27 Douglas Haynes, in his recent book, Small Town Capitalism in Western India (2012) focused on an overlapping, but extended period from 1870 to 1960, and researched in depth the textile economies of Western India and Gujarat. His analysis of the cycles of small scale industry over this long period charts not the great decline of the textile economy, but a resurgence of small producers. He argues a case for the rise of ‘weaver capitalism’ in small manufacturing centres; the old handloom towns renewed their cloth manufacture with small producers using electric power. A small-scale power loom industry in karkhanas or workshops with multiple looms, radically changed a textile economy which by the 1930s was dominated by the disjuncture of large-scale mills and declining handloom manufacture. From the 1940s these karkhanas diversified their output and adopted electric or oil powered looms. They sought plant and equipment in Japan and Belgium, built new dyeworks and developed innovative product lines. At the end of the twentieth century Western India’s small weaving towns became large urban agglomerations with millions of looms, the cloth manufacture located in tight enclaves. Late twentieth-century structures included a wide variety of small and large firms, and skilled artisans work alongside pools of casual labour from non-artisanal backgrounds. An informal economy has been reshaped, he argues, out of long historical change and struggles over trade unions and labour legislation over the course of the 11 twentieth century.28 One side of that informal sector consisted of firms seeking locations and ways where they could avoid India’s tightening factory legislation; precisely the kind of legislation that was not enforced in Bangladesh’s clothing sector. Haynes thus deconstructs the binaries that inform the historiographies of India’s de-industrialization: handloom and powerloom, craft and industry, artisan and factory work, and informal and formal sectors of the economy. 29 Western India’s textile history is, furthermore, not one of simple transition from artisan-based production for local markets in the pre-colonial period to one of commercialization in the nineteenth century, and on to globalization in the late twentieth century. The factory textile industry of Bombay and Ahmedabad that disappeared, did not mean the end of the textile industry. [Haynes recognizes that the cycles of small producer capitalism he charts over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had deep historical roots in a wide Indian Ocean and global trade, and versions of the mixed workshop and family economy embedded in networks of middlemen and sub-contractors in eighteenth-century Surat and other textile towns of Gujarat.30] A Global History of Craft and Small Industry in the Twenty-first Century Haynes’ investigation of the industrial cycles and recent economic development of the textile manufacture of Western India relies on many local gazetteers, reports and industrial surveys. It also draws on over 200 interviews with artisans, workers, merchants, industrialists and industry experts. Interviews and oral histories also provide a way to connect the globalized world the crafts and small industries now inhabit with that eighteenth-century world of Indian Ocean and global trade in luxury goods. Interviews and oral histories take us into the methods of archaeologists, some of whom see themselves practicing ‘ethno-archaeology’; others simply seeking another way of accessing local material cultures and technologies. Archaeologists have used analogical reasoning, observing and interrogating living communities in the regions where they seek to reconstruct material cultures of pre-historic production centres. Other archaeologists practice a method of ‘experimental archaeology’, reconstructing technologies from site findings. Likewise, historians of science have reworked historical experiments to understand the ‘tacit’ aspect of the experimental process. Similar methodologies help to connect understandings of current production processes with those for global markets in the eighteenth century. Haynes and Roy have charted not just the long continuity of small-scale manufacturing over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but a reshaping of informal sectors in 12 response to local, national and more recent global markets, technologies and the state. Liebl and Roy’s assessment for India as a whole in 2003 found a large dynamic handicrafts sector, employing approximately 9 million, and gaining under freer markets, but needing sophisticated adaptation to new consumers.31 The crafts and small producer sectors of Kachchh are a part of a new story of global history and craft production. As in other parts of India, producers faced a decline in traditional domestic markets with the competition of factory goods, synthetic fabrics, screen printed prints and mass produced bandhani. 32 The state and NGOs have played a part, especially since the 1980s, in building infrastructure, information exchange, and business aid as well as a programme of national craftsman awards and support for travel to international exhibitions. There is some limited access to international outlets, such as Vancouver, Canada’s Maiwa.33 My research in the area has given me some sense of the great difficulty in accessing these goods for world trade during the early modern period. Distances are great, and travel is not straightforward; even by 1951 the railroad only reached 72 miles into the region. Yet in the eighteenth century fine European mirrors, glass and china ware were brought via Mandvi over this land area to the royal court of Rao Lakhpatji at Aina Mahal in Bhuj, and the fine manufactures of Kachchh were traded out from there and other ports on its coast. I have led a project to collect the oral histories of a number of craftspeople and their families during the past year. Working with two assistants, Mohmedhusain Khatri in the region, and Dr. Chhaya Goswami Bhatt of Mumbai, herself a historian of Kachch, we have deposited the interviews on a website, and summarized these in written English and Gujarati. This web resource provides not just a source for my own and other historians’ research, but a public record of the family histories of the region’s skilled workforce, one to which they can continue to add. Interviews with nearly seventy artisans and their families show deeplyembedded craft communities, some going back many generations, but several with fluid work histories, with some generations or parts of families leaving the craft, and subsequently returning. Many tell migration stories from other parts of Gujarat, from Rajasthan and from Sindh. They show a number coming from farming backgrounds, or continuing to combine their work as artisans with farming or coolie work. They show us high levels of specialization and division of labour, and adaptation to new materials and technologies. High success rates in international markets for some contrast with extreme struggles for survival among others. Even within the most successful businesses craftsmanship sits with low wages and alienated labour. The resilience of this craft node relies on 13 its local as well as its global markets; producing the quality luxury goods adapted to the designs of world trade provides a possible competitive edge. But continuing to produce for the local sumptuary codes of the tribal people and local communities is also crucial. Among the most successful of these artisans are the ajrakh printing artisans from the villages of Ajrakhpur and Damadka near Bhuj, and a group of woollen and cotton weavers from the village of Sarli. Both are well-integrated with international markets and exhibitions, national award schemes, NGOs and design institutes. The Khatri family of printers sell to Maiwa in Canada, to Fab India, and to many other international buyers through exhibitions. The weavers get bulk orders from exhibitions and sell to Malaysia, Brazil, Milan, Paris, London, Colombo and Singapore. Some trade through a large wholesaler, Kantibai, or agents from Mumbai and Delhi. Both also continue to supply traditional local tribal markets, the Rabari, Ahir and Patel communities. The Khatris of Damadkha date their residence from the sixteenth century, with ancestors coming from Sindh. Some of the older weavers of Sarli and Bhojodi date their families’ work in the craft back four generations; others have entered more recently out of farming communities, and some migrated in generations past from Rajasthan.34 Bandhani, practiced for many generations across Kachchh provides the sumptuary codes of many communities, especially for marriages, and also now for wide national and international markets. Centres in Mandvi, Mundra and Bhuj supply the Kadarbhai firm; the finest work goes to international exhibitions, NGOs and buyers such as Maiwa. Some families have returned to the craft after some generations in other occupations, and women practice it as part of the daily routines of their lives.35 Access to international and wider national markets is key to craftspeople in the region, especially in cases where there have been recent dislocations in local markets. Those experiencing much greater difficulty are those who have little access to these markets, such as the cutlers of Mota Reha who have also worked for generations in their trade, selling their knives through agents taking them to local markets throughout Gujarat. Their fine swords, celebrated back to the early modern period, appear in international exhibitions and sell for ceremonial use in Kachchh and the Punjab International markets, NGOs and government schemes have created opportunities in this craft sector for many small businesses. Some are like the later twentieth-century weaver capitalists described by Douglas Haynes. But all of these crafts contain a division of labour either within families, or deploying groups of labourers specialised to one task. Unless connected through business or family to sources of capital, they are wage and piece workers confined to one 14 task. The women working in bandhani tie and dye and batik workers never learn the exclusive skills of dyeing. The ajrakh printers pound their blocks, never missing an alignment day in and day out for years to come from the age of 10 or 12. A washer, Haddu Babubhai, has spent 25 or 30 years in the washing vats, making all the hidden colour sparkle to the surface.36 All the processes of cutlery making are divided into seven or more separate processes, workshop by workshop; Abdul Rashid has made wooden handles for knives for 35 years.37 Women are closely engaged in many family crafts, in mochi work, bell making, and weaving, and more recently in rogan and batik work. Haynes found new opportunities opened by technological change as well as the well-known histories of the decline of the handloom sector. Technology has brought diverse experiences to the craftspeople of Kachchh in the later twentieth and the twenty-first centuries. The weavers have adopted the hand fly shuttle over the past forty years, and have greatly increased their productivity. Samji and Ramji ~Visram Siju, weavers of Bhojodi improved their markets by shifting during the 1960s to a softer weave, but were deeply affected from 1995 by competition from power loom cloth from the Punjab which flooded their markets. Cutlers have kept their ancient forging technologies, but have adapted all their processes to small electrical motors. Printers and batik workers debate the impact of chemical and natural dyes. Chemical dyes introduced into ajrakh printing in the 1960s met local demands for brighter colours, but high quality international market demanded a return to natural dyes, and investment in training and skills in the use of natural dyes. The focus of international customers on natural dyes has closed off markets for batik workers who cannot yet adapt their techniques to these dyes. The craft groups of Kachchh know the long histories of their families in their trades. Some know of a deeper history of trading their fine craft goods in the pre-colonial Indian Ocean World. Some such as the textile printers are adapting the product designs of museum collections. Conclusion Interviews and oral histories among the craftspeople of Kachchh today convey to us a world of high quality goods produced within strong craft communities and providing both goods for local sumptuary and everyday use in the region as well as products for globalized markets. The region provides a unique setting 15 for investigating the impact of globalization and new technologies on embedded craft skills. The deep history of this craft economy also makes it a place for the use of analogies between the present and the past. The things carried out of the region as fine art objects by merchants and the East India Company into Europe’s domestic interiors and later museums were most likely made in small village workshops or in outwork or proto-industrial settings. We can suggest that craft work, then as now, was a divided process involving merchants and master craftsmen/designers and a range of specialized labourers, uneducated and with no access to the capital that might raise them in time to become master craftsmen themselves. The descriptions we do have left by eighteenth-century travellers convey as much. The opportunities and challenges of new national and global markets now are helping some; others seek these. What will the future hold for these people? Will they go the way of Europe’s protoindustrial workforces into the chemical factories setting up nearby, or to cheap garment factories such as those of Bangaladesh, or will its young people leave for Mumbai’s streets, seeking that exciting metro life. Or will the variety and quality they can produce contribute to enlarged global markets which seek differentiation as well as standardized goods? We don’t yet know. But thus far, these crafts have survived over our long world history of industrialization, and of India’s colonial, national and global transitions. They challenge our models of industrialization; they have survived because they have innovated and adapted to new markets. Manufacture is something that many European historians have lost interest in. But our own histories are now global histories. We wear those clothes made in Dhaka; just as we bought those textiles made in Gujarat in the eighteenth century. How it is made is not just a question of Asian economies and histories; it is our history, and it is a global history. 1 Abigail McGowan, Crafting the Nation in Colonial India (New York: Palgrave, 2009); Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty: 136-44. Also see the discussion of displaying and collecting Indian craft skills in silk manufacture in international exhibitions from the mid-nineteenth century in Brenda M. King, “Exhibiting India.” In Silk and Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), chap. 6. 2 See P. Parthasarathi, ‘The History of Indian Economic History’, unpublished paper, 2012. 3 See M.D. Morris, “Towards a Reinterpretation of Nineteenth-Century Indian Economic History.” Indian Economic and Social History Review 5 (1968): 1-15; T. Raychaudhuri, “A Reinterpretation of Nineteenth Century Indian Economic History?” Indian and Economic and Social History Review, 5 (1968): 77-100; A.K. Bagchi, “De-industrialization in India in the Nineteenth Century: Some Theoretical Implications.” The Journal of Development Studies 12 (1976): 135-64; C. Simmons, “‘De-industrialzation’, Industrialization and the Indian Economy, c. 1850-1947.” Modern Asian Studies 19 (1985): 593-622. 16 4 Alexander Walker Papers, The National Archives of Scotland. Order Lists of the English East India Company: E/3/96/18, India Office Records, British Library. Derived from Europe’s Asian Centuries EIC trade database, unpublished. 6 Nadri, “Exploring the Gulf of Kachh”: 462, 466, 468-9, 478-9. 7 Ibid., 473. Also see C. Markovits, “Indian Merchant Networks Outside India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Preliminary Survey.” Modern Asian Studies 33 (1999): 883-911, esp 899. 8 Nadri, “Exploring the Gulf of Kachh”: 470. 9 J. Tod, Travels in Western India embracing a visit to the sacred mounts of the Jains… (London: Wm. H. Allen & Co., 1839):449. 10 Ibid., 453. 11 A. Tyabji, Bhuj: Art, Architecture, History (Mumbai: Mapin, 2006): 9-16. 12 L.F. Rushbrook Williams, The Black Hills: Kutch in History and Legend (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1958): 136-47; Tyabji, Bhuj: 34-5. 13 C. London, The Arts of Kutch (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2000). 14 Edwards, Textiles and Dress of Gujarat: 28-30; E. Edwards, “Contemporary Production and Transmission of Resist-dyed and Block-printed Textiles in Kachchh District, Gujarat.” Textile 3.2 (2005): 170. 15 See IOR G/36, Surat Factory Records 73, Surat Proceedings 11 September 1795: The Chief’s Minute. The Commercial Board, 453-4. Detailed discussion based on the Enquiry can be found in Nadri, Eighteenth-Century Gujarat, 146; L. Subramaniam, Indigenous Capital and Imperial Expansion: Bombay, Surat and the West Coast (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1966); L. Subramaniam, “The Political Economy of Textiles in Eastern India: Weavers, Merchants and the Transition to a Colonial Economy.” In How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500-1850, eds G. Riello and T. Roy (Leiden: Brill, 2009): 258-280. 16 A revised and edited version of the Journal kept by Hove on his expedition was published as Tours for Scientific and Economic Research made in Guzerat, Kattiawar, and the Conkuns in 1787-88 by Dr. Hove (Bombay: Selections from Records of the Bombay Government, no. 16, 1855). Passages used here where possible are from the extracts to Hove’s journal in the India Office Records collection in the British Library: ‘Extracts from Dr. Hove’s Journal’, BL, IOR, Home Miscellaneous 374: 591-665. 17 Tours for Scientific and Economic Research: 176-8; Extracts from Dr. Hove’s Journal, 642-4. 18 Extracts from Dr. Hove’s Journal, 625, 642-4. 19 Williams, The Black Hills: 182-8. 20 NLS, Walker Papers, Ms. 13841: ‘Letter to Francis Warden, Chief Secretary to the Government, 25 April, 1809’, 494, 513,514. 21 NLS, Walker Papers, Ms. 13861-3: ‘An Account of Castes and Professions in Guzerat’, with two draft volumes, compiled c. 1823. 22 M. Postans, Cutch or Random Sketches taken during a Residence in One of the Northern Provinces of Western India interspersed with Legends and Traditions (London: Smith, Elder and Co. Cornhill, 1839). Edition by Asian Educational Services, New Delhi and Madras, 2001. On Postans see R. C. Raza, “Young, Marianne (1811-1897).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online, www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/48646, accessed 3 January, 2013. 23 Postans, Cutch or Random Sketches, 14. 24 Ibid., 173. 25 Ibid., 257-8. 26 T. Roy, Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999): 3-6, 232-5. 27 Ibid., 7. 28 D. Haynes, Small Town Capitalism in Western India: Artisans, Merchants, and the Making of the Informal Economy, 1870-1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012): 265, 272-7, 311. 29 Ibid., 3-5. 30 Ibid., 24-36. 31 M. Liebl and T. Roy, “Handmade in India: Preliminary Analysis of Crafts Producers and Crafts Production.” Economic and Political Weekly 37 (27 December 2003), 5366-76. 32 Edwards, Textiles and Dress of Gujarat: 126-7. 33 http://www.maiwa.com/home/documentaries/. Interview with Charlotte Kwon, Director, Maiwa, Vancouver, 9 July, 2012. 34 Interviews with Ismail Khatri, Ajrakhpur, 15 February 2012; Kantilal Vankar, Sarli, 26 May 2012; Shamjibhai Visram Siju (Vankar), Bhodjodi, 27 May 2012. 35 Interview with Hanifa Yusuf Sumra and Jamila Ramju Sumra, and Hawabai Sumra, Mandvi, 16 February 2012; Interviews with Abdullah and Mohmedhusain Khatri, 3 July 2011. 5 17 36 Interviews with Imtiaz Araby Khatri and Haddu Babubhai, Ajrakhpur, 27 February 2012; Interview with Shakeel Mohammed Qasim Khatri, Mundra. 37 Interview with Abdul Rashid, cutler, Mota Reha, 17 February, 2012; Interviews with bellmakers Luhar Janmamad Sale Mohammed and Kanji Devji Maheshwari, Zura, 26 May 2012; Interviews with Rumar Daud Khatri and Abdul Gaful Khatri, Rogan makers, Nirona, 26 May 2012.