The development of cognitive control in children with Heather M. Shapiro

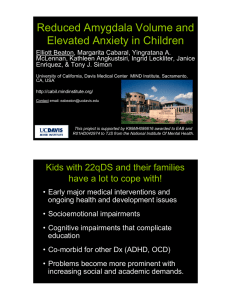

advertisement