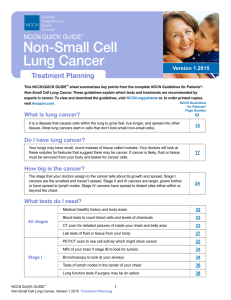

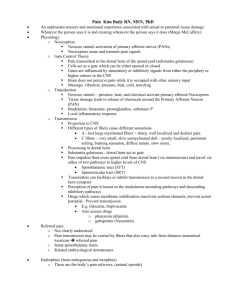

Adult Cancer Pain NCCN.org Version 1.2014

advertisement