ACCOMMODATING RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PREVENTING HARASSMENT CLAIMS IN THE WORKPLACE

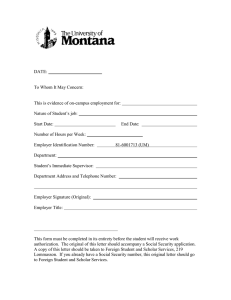

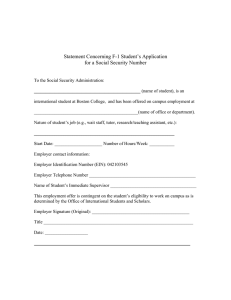

advertisement

ACCOMMODATING RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PREVENTING HARASSMENT CLAIMS IN THE WORKPLACE I. Introduction Both Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)) and the Washington Law Against Discrimination (RCW 49.60) prohibit discrimination on the basis of an individual’s religion (or “creed,” which is the term used in RCW 49.60.180(2)). Title VII was amended in 1972 to also provide for an affirmative duty on the part of employers to accommodate the religious beliefs and practices of employees. The term “religion” includes all aspects of religious observance and practice, as well as belief, unless an employer demonstrates that he is unable to reasonably accommodate to an employee’s or prospective employee’s religious observance or practice without undue hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(j); TransWorld Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63, 74 (1977). In contrast, the Washington anti-discrimination statute contains no “reasonable accommodation” language and our Supreme Court has stated: [F]ederal and state law against discrimination in employment are significantly different. Federal law expressly impose an affirmative duty upon an employer to accommodate the religious beliefs and practices of its employees. Washington law contains no such express requirement . . . . Whether the Washington statute may implicitly require accommodation is an important and complex question that we have not previously been asked to decide . . . . Without adequate briefing on this important issue, we decline to decide it. Further, we specifically disapprove that portion of the Court of Appeals decision in this case which assumes that our state statute against discrimination based on creed is identical to the federal law. Hiatt v. Walker Chevrolet Co., 120 Wn.2d 57, 837 P.2d 618 (1992).1 Notwithstanding the Hiatt decision, most employers of more than 15 employees are subject to Title VII and are obligated “to reasonably accommodate” an employee’s religious beliefs and practices, unless it would present an “undue hardship” to the employer.2 1 In Hiatt, the Supreme Court analyzed the plaintiff’s claim of religion-based discriminatory discharge under federal law, and affirmed the trial court’s summary judgment of dismissal. 1 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP This paper addresses employer duties not to discriminate on the basis of “religion” or “creed” under both federal and state law, including the three broad areas of (a) disparate treatment, (b) religious harassment, and (c) at least under federal law, the duty to accommodate. Not surprisingly, individual fact patterns will often overlap these analytic distinctions. II. Disparate Treatment. The EEOC has defined “religion” broadly to include: . . . moral or ethical beliefs as to what is right or wrong which are sincerely held with the strength of traditional religious views. . . . The fact that no religious groups espouses such beliefs or the fact that the religious group to which the individual professes to belong may not accept such belief will not determine whether the belief is a religious belief of the employee. The phrase “religious practice” as used in these guidelines includes both religious observances and practices. . . . 29 C.F.R. § 1605.1.3 Under Title VII, the elements of a prima facie case of disparate treatment based on religion are similar to the elements of a prima facie case based on any other protected category. They are: • The employee belongs to a protected class because he or she has a bona fide religious belief or practice; • The employee’s job performance was satisfactory (discipline or discharge cases) OR the employee was qualified for the job he or she sought (failure to hire/promote cases); • The employee was disciplined or discharged OR the employee was not hired or promoted OR the employee suffered some other adverse employment action; and (. . . continued) 2 Not all employers of more than 15 employees are subject to Title VII. Religious organizations themselves are exempt from both Title VII and RCW Chapter 49.60. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l (which provides that Title VII does not apply to religious organizations “with respect to the employment of persons of a particular religion to perform work connected with the carrying on by such [organization] of its activities”); RCW 49.60.040(3) (the term “employer” “does not include any religious or sectarian organization not organized for private profit”). 3 Atheism is also protected as a reflection of the freedom “not to believe.” 2 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP • Some similarly situated employee outside the protected class was treated differently/more favorably. Religious discrimination cases also use the burden shifting process used in race, gender or other kinds of Title VII cases. As in other disparate treatment cases, the employee will bear the ultimate burden of persuasion. A similar approach is used in cases brought under RCW Chapter 49.60. For example, in Nielson v. AgriNorthwest, 95 Wn. App. 571, 977 P.2d 613 (1999), the court held that an employee who suffered numerous adverse actions from his Mormon supervisor after he left the Mormon church had “present[ed] a scenario that on its face suggests the defendant more likely than not discriminated,” and reversed the trial court’s summary judgment in favor of the employer. The Court of Appeals remanded the Nielson case to the trial court with instructions to resolve the factual issues raised by the employer’s asserted “legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons” for its adverse actions against the employee. III. Religious Harassment. All of the case law applicable to sexual or racial harassment claims will apply to claims of “hostile work environment” based on religion. In one recent Sixth Circuit case, the Court of Appeals affirmed the employer’s summary judgment on the employee’s claim of hostile work environment because of religion (Muslim), but reversed and remanded for trial the claim of race-based hostile work environment. The court made clear, however, the admissibility of evidence regarding hostility based on the employee’s religion and its applicability to strengthen his race discrimination claim: We recognize that the overall harassment [plaintiff] experienced may not have been based exclusively on his race but also on hostility to him as a ‘black Muslim.’ In at least one instance . . . the link between the racial and religious bias was explicit. The theory of a hostile-environment claim is that the cumulative effect of ongoing harassment is abusive. It would not be right to require a judgment against [plaintiff] if the sum of all of the harassment he experienced was abusive, but the incidents could be separated into several categories, with no one category containing enough incidents to amount to ‘pervasive’ harassment. Although there is enough evidence of racial harassment for that claim to stand on its own, the district court should allow at trial for consideration of the possibility that the racial animus of [plaintiff’s] co-workers was augmented by their bias against his religion. Hafford v. Seidner, 183 F.3d 506, 514- 515 (6th Cir. 1999). In another religious harassment case, the Seventh Circuit held that an employee stated a claim for workplace harassment when her supervisor subjected her to sermons on personal topics, accused her of leading a sinful life and made it clear that she would be fired if she did not follow her supervisor’s religious dictates. Venters v. City of Delphi, 123 F.3d 956, 973-74 (7th Cir. 1997) 3 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP Of course, any employer who has not updated its anti-harassment policies since the United States Supreme Court decisions in Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth and Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, should do so promptly. All anti-harassment policies should include language prohibiting harassment on the basis of all protected categories, including religion, and provide an easy-to-use complaint procedure, which is disseminated to all employees. IV. Failure to Accommodate. By far, the most frequent religious discrimination questions arise when an employee seeks an accommodation. Most failure to accommodate cases generally involve (1) scheduling/ leave requests, (2) dress and grooming issues, (3) substantive job duties which create a conflict, or (4) co-worker evangelizing. As noted above, Washington State law does not clearly create an affirmative duty regarding religious beliefs or practices. However, there are numerous Title VII cases in this area and employers should anticipate that the Washington Supreme Court will, at some point, address the accommodation issue that they declined to resolve in Hiatt v. Walker Chevrolet. The elements of a prima facie failure to accommodate claim are: • a bona fide religious belief or practice that conflicts with an employment requirement; • notice to the employer of the conflict; • discipline for failing to comply with the conflicting employment requirement compliance under protest following threat of discipline. OR In Heller v. EBB Auto Co., 8 F.3d 1433 (9th Cir. 1993), the Ninth Circuit emphasized the reluctance of the courts and, therefore, the inadvisability of employer-scrutiny of the “necessity” of the asserted religious belief or practice. However, employers and courts may inquire whether the belief is “in the employee’s own scheme of things, religious.” Id. at 1438. Once an employee has made out a prima facie case, the burden will shift to the employer to demonstrate that an accommodation would result in “undue hardship.” The “undue hardship” test for accommodation of religious beliefs and practices is very different than the “undue hardship” test under the Americans with Disabilities Act. In the context of accommodating religious beliefs and practices, the Ninth Circuit holds that an employer: . . . may prove that an employee’s proposal would involve undue hardship by showing that either its impact on co-workers or its costs would be more than de minimus. Bhatia v. Chevron USA, Inc., 734 F.2d 1382, 1384 (9th Cir. 1984) (challenge by Sikh employee to new work rule requiring machinists to shave facial hair to ensure gas tight seal on respirator 4 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP rejected). However, in more recent cases, the Ninth Circuit has made clear that simply asserting an “undue hardship” will not suffice. The employer must at least attempt to make a reasonable accommodation. The employer must: . . . show that it undertook some initial step to reasonably accommodate the religious belief of that employee . . . [which] requires that at a minimum, the employer . . . negotiate with the employee in an effort reasonably to accommodate the employee’s religious beliefs. Heller v. EBB Auto Co., 8 F.3d at 1440 (citations omitted); see also Balint v. Carson City, Nevada, 180 F.3d 1047, 1055-56 (9th Cir. 1999) (en banc) (employer should have considered voluntary shift trades or shift splitting before refusing employee request not to work on her Sabbath). A. Scheduling/Leave Issues. As noted above, employers cannot simply refer to their established scheduling practices or bona fide seniority systems to establish that granting an employee a particular schedule or leave for religious purposes would be an “undue hardship.” Instead, the employer must seriously consider the level of impact that granting the request would have on its operations. Balint, 180 F.3d at 1054; see also EEOC v. Ilona of Hungary, 108 F.3d 1569 (7th Cir. 1997). In Ilona of Hungary, the Seventh Circuit ruled in favor of two hairdressers who asked to take a day off to observe Yom Kippur. The employees gave advance notice; however, the salon where they worked refused their leave request and scheduled customers for them. The employees did not come to work that day and were fired. The court rejected the employer’s argument that because Yom Kippur fell on a Saturday, which was always the salon’s busiest day, the leave request imposed an undue hardship on the employer. Instead, the Court ruled that the particular Saturday in question was no busier than any other and that the employer’s loss of income could have been avoided if the employer had allowed the two hairdressers to reschedule their customer appointments for different days. Id. at 1576-77. Title VII does not require paid leave for religious observances, nor does it require an employer to hire additional or temporary employees at higher salaries. Similarly, courts will generally find that productivity and operational losses caused by religiously-motivated leave or scheduling requests will constitute an “undue hardship” when the cost to the employer is more than de minimis. B. Dress and Grooming. Safety issues, when supported by evidence, will almost always support an “undue hardship” defense. For example, employees who cannot remove a turban to wear a hard hat in construction zones may be reassigned or, if there is no work available to which they can be reassigned, can be terminated. Kalsi v. NYC Transit Auth., 62 F. Supp. 2d 745 (E.D.N.Y. 1998), aff’d, 189 F.3d 461 (2d Cir. 1999). In the Bhatia case mentioned above, the Ninth Circuit noted that the employee who refused to shave his beard in order to obtain a “gas tight” seal on his 5 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP respirator had been offered four different positions that did not require respirator use. Bhatia, 734 F.2d at 1384. Although the “undue hardship” test of Title VII is a much narrower test than the “undue hardship” test under the ADA, one court relied on evidence that the employer had made an ADA-based accommodation for police officers who were given an exemption from a “clean-shaven only” rule for medical reasons to conclude that allowing religiously-based exemptions from the same rule would impose only a de minimis burden on the police department. The court reasoned the department already employed bearded police officers because of the ADA accommodation and, therefore, allowing other bearded police officers would not present a significantly different or heavier burden. Fraternal Order of Police v. City of Newark, 170 F.3d 359, 366-67 (3rd Cir.), cert. denied, 120 S. Ct. 56 (1999) (applying strict scrutiny to constitutional free exercise of religion challenge). C. Job Duties. Often a particular aspect of an employee’s job duties will conflict with a religious belief or practice. Courts generally look to see whether a similar job exists that does not require the employee to perform the offensive duty, but will defer to the employer in most cases. As with ADA accommodation issues, an employer need only offer a reasonable accommodation, but not necessarily the accommodation sought by the employee. For example, a Catholic police officer who did not want to perform security duties for an abortion clinic was deemed reasonably accommodated when the city offered him a transfer to a district which did not have an abortion clinic even though the employee desired to stay in his originally assigned district but without “clinic duty.” Rodriguez v. City of Chicago, 156 F.3d 771, 776-77 (7th Cir. 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 1038 (1999). Similarly, an atheist telemarketer, who was uncomfortable reading scripts for religious-based groups, was transferred to a group that read scripts which marketed a psychic line. She was fired because she refused to read those scripts either, although the company’s policies allowed her to refer to the psychics as “gifted” rather than read text that referred to the psychics as “god gifted.” McIntyre-Handy v. West Telemarketing Corp., 97 F. Supp. 2d 718, 735-36 (E.D. Va. 2000). Likewise, a trucking company’s unwillingness to ensure that a truck driver who was a Jehovah’s Witness never be assigned overnight runs that included a female partner was upheld on the ground that such scheduling imposed more than a de minimis burden on the employer’s operations. Weber v. Roadway Express, 199 F.3d 270, 275 (5th Cir. 2000) D. Proselytizing at Work or to Fellow Employees. This is a growing area of accommodation law as employers struggle to balance the accommodation claims of employees whose beliefs require them to proselytize or “bear witness” at work with the potential religious harassment claims of fellow employees who do not want to 6 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP hear religious communications from co-workers or (worse from the perspective of employer liability) supervisors. Again, as with employees whose religiously-based refusal to perform certain job duties, courts will generally uphold discipline for employees who proselytize in the workplace. Accordingly, in Chalmers v. Tulon Co., 101 F.3d 1012, 1019 (4th Cir. 1996), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 58 (1997), an employee was fired after she sent letters to supervisors and subordinates at their homes accusing them of immoral conduct and recommending that they accept God and change their lives. The court affirmed her discharge, noting that accommodation of this conduct would expose the employer to claims from the recipients of the letters. Similarly, in Wilson v. U.S. West Communications, 58 F.3d 1337, 1341 (8th Cir. 1995), the Court found that allowing a Catholic employee, who had made a vow to be a “living witness” until abortion was ended and therefore, wore a button that contained a color photograph of a fetus, was reasonably accommodated by being allowed to wear the button uncovered only while in her cubicle (or to wear a different, less graphic button), but was required to cover the button when interacting with others. V. Conclusion. With regard to disparate treatment or harassment concerns, employers should be as conscious and sensitive to their legal obligations under Title VII and RCW 49.60 not to discriminate on the basis of religion or creed as they are with regard to other protected categories. Accommodation issues involving safety, job duties or proselytizing will generally be resolved in favor of the employer. Accommodations involving leave or scheduling requests are scrutinized more closely and employers must be prepared, even when scheduling is governed by a bona fide seniority system or other longstanding practice, to demonstrate an attempt to work out a solution. 7 Gail E. Mautner Mautnerg@lanepowell.com 206-223-7099 746359.1 © 2000 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP