Environs Recent Developments in Environmental Law In Th is Issue: Winter 2005-2006

advertisement

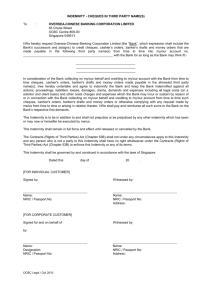

Environs Recent Developments in Environmental Law Winter 2005-2006 In This Issue: • USTs: New Rules Focus on Training and Inspection • EPA Adopts Final Rules for PHASE I Environmental Site Assessments • Let’s Twist Again: Another Round of the CERCLA Dance • Environmental Indemnity: Not Necessarily the Safety Net Property Buyers Expect Environmental LAW USTs: New Rules Focus on TRAINING & INSPECTION By Michael A. Nesteroff help states pay for tank cleanups when owners or operators could not or would not pay for cleanup. Amid lengthy and controversial provisions in the Energy Policy Act signed into law last summer is the first major overhaul of federal underground storage tank rules since 1994. Although it received relatively little notice, the Underground Storage Tank Compliance Act (“USTCA”) means substantial changes for owners and operators of underground storage tanks (“USTs”) including, for the first time, federal, state and local governments that own and operate underground tanks. Between 1988 and 2004, the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) and states identified nearly 450,000 confirmed releases from USTs nationwide, almost threefourths of which have completed cleanup (Washington’s cleanup rate is closer to two-thirds of the 6,084 confirmed releases, while Oregon has completed cleanup on nearly 80 percent of its 6,865 confirmed releases). Although the number of confirmed releases has declined significantly in recent years, a number of problems were still occurring. Studies by states like South Carolina, Florida and California generally found that releases were most likely where there was no secondary containment find, and that overfills and spills during deliveries also were common causes of contamination. The studies concluded that sight and smell were the best leak detection and there was a high potential for vapor leaks. Energy Bill In 1984, Congress created the UST program to regulate the more than 2 million tanks around the country (although it exempted home heating oil and small tanks used on farms). The legislation required owners to install new leak detection by the end of 1993, and new spill-, overfill- and corrosion-prevention devices by the end of 1998. Owners who did not meet those conditions by the deadline were supposed to close or remove the tanks. In 1986, Congress established a trust fund, replenished primarily through a tax on gasoline and other fuels, to The Government Accounting Office (“GAO”) performed 1 Winter 2005-2006 its own study and concluded that improved inspections and for tanks in rural or remote areas where treating a UST as enforcement, together with more funding, would make ineligible for delivery would jeopardize the availability or the UST program more effective. Over the years several access to fuel for the community. efforts were started in Congress to implement the GAO recommendations, but none managed to become law until this last summer with the adoption of the USTCA. The key theme underlying the law is a shift towards inspection and training. Mandatory Inspections The USTCA requires owners and operators inspect within two years all tanks that have not been inspected since December 1998. Beginning in 2007, after completion of the first round of inspections, states will have to inspect all USTs at least once every three years. Until the new federal law, Washington and Oregon had their own laws that required inspection every three years, but only for tanks that had some form of corrosion protection system. For tanks in Washington and Oregon that are lined, the state laws only required inspections every five years after the first ten years from lining. The USTCA changes this by treating all tanks the same for inspection purposes. With 10,459 active USTs in Washington and 6,448 active tanks in Oregon, the new law greatly expands the number of tanks that will have to be inspected in the next two years. The states may have some flexibility in how they conduct inspection programs, since the USTCA provides for adoption of alternatives to traditional inspection programs after the states and federal EPA gathered information about compliance assurance methods. This could include having third parties conduct inspections, or allowing owners and operators to self-certify compliance. Mandatory Training The new federal law also contains UST training requireRestricted Delivery ments for operators, managers and employees. Within In conjunction with the inspection requirement, the two years EPA is required to develop guidelines for trainUSTCA has added a civil penalty provision for anyone ing, and the states then would have two years after that who delivers or accepts delivery of a regulated substance, to develop state-specific training requirements consistent such as gasoline, into a UST that has not passed inspec- with the federal guidelines. The law directs the states to tion. The delivery prohibition is similar to existing regu- develop their rules in cooperation with tank owners and lations in Washington, Oregon and Alaska, but it adds a operators, and to take into account owners’ and operators’ requirement that each state keep a roster of prohibited existing training programs. delivery sites. This list must be developed within two years and made readily accessible on-line. The federal law This provision represents a significant expansion of obalso contains an exemption from the delivery prohibition ligations for tank owners and operators in Washington, 2 Environmental LAW to exempt USTs that he determines “to be in the paramount interest of the United States to do so.” Such exemptions are good for one year at a time and cannot be granted due to a lack of appropriation, unless the President specifically asked for money and Congress failed to provide funding. Thus, if exercised, the “paramount interest” exemption has the potential to keep many federal facilities out of state jurisdiction. Oregon and Alaska. Right now neither Washington nor Alaska have any current training requirements, and Oregon has a mandatory training program only for a designated UST operator at each site. Funding Many states were hard-pressed to fund vigorous inspection and enforcement programs under the old law, particularly since money set aside in the federal trust fund could only be used to pay for state-conducted cleanups. To address this, the USTCA provides that up to 80 percent of the trust fund, now estimated at over a billion dollars, can be used by the states to fund compliance and enforcement programs. The reallocation of trust funds, however, will not help owners and operators who have to clean up a tank site, since the law still prohibits the states from using the money to provide financial assistance for cleanups. Where states have their own trust funds, the law also will not allow using the federal trust funds to replenish state trust funds shifted to balance their general fund. Secondary Containment After February 8, 2007, the USTCA requires secondary containment for all new or replaced tanks or pipes within 1,000 feet of a community water supply or drinking water well. When a tank or pipes are replaced, only the replacements, and not other USTs or pipes already connected to the system, need to have secondary containment. Motor fuel systems also will have to have spill containment under the dispensers. These requirements do not apply when repairs are made to a UST or piping. Manufacturers and installers of USTs or piping will have to maintain evidence of financial responsibility for the cost of corrective actions directly related to releases caused by improper manufacture or installation. States will have G o v e r n m e n t to require installers to have certification and will have to inspect each installation. USTs For the first time, underground tanks Bottom Line owned by federal, The USTCA is an ambitious attempt to address many of state and local gov- the issues that the GAO study raised, but it remains to be ernment agencies are subject to regulation, putting them seen whether those measures will be effective. While some on the same footing as private owners and operators of of the problems identified over the past 20 years might USTs. The law requires state and local governments to be remedied with inspection and training, the increased bring their USTs into compliance within two years. States oversight is not likely to be very popular with UST ownwill have to make publicly available a list of all the govern- ers and operators, and it adds burden on state regulators. ment USTs that do not comply and specify the actions Even so, as the state studies indicate, there are sources of contamination – such as overfills, spills and vapor leaks needed to bring the tanks into compliance. – that neither the old law nor the USTCA have tackled. Federal agencies have a year to develop compliance- Consequently, it is unlikely that the USTCA will be the reporting standards for their USTs. As an added incentive last word on underground tank regulation. to federal agencies, the new law expressly waives sovereign immunity and allows states to impose fines and penalties Michael Nesteroff focuses on environmental litigation in our Seattle office and was chair (and guitar player) in the “Lawyerpalooza Battle of the Law against federal facilities for UST violations. Firm Bands,” an extremely successful event held to raise funds for elementary school music programs. nesteroffm@lanepowell.com While this gives states the opportunity to regulate, for example, USTs on military bases, the law allows the President 3 Winter 2005-2006 UPDATE: EPA ADOPTS FINAL RULES FOR PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL SITE ASSESSMENTS When Congress amended CERCLA in 2002, it directed the EPA to draft rules for “all appropriate” inquiries. Now, three years later, EPA has issued the final rule that establishes detailed requirements and standards for conducting environmental due diligence of commercial and industrial real property and operations. The AAI rule replaces the previous de facto standard for Phase I assessments performed according to the American Society for Testing and Materials (“ASTM”) Phase I (Standard El527-97). A copy of the new rule is available through the EPA website, www.epa.gov/swerosps/bf/regneg.htm. After a lengthy process, the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) in early November 2005 issued its final All Appropriate Inquiry (“AAI”) rule, which sets out the first federal standards for conducting Phase I Environmental Site Assessments. Effective November 1, 2006, anyone who purchases, finances or refinances commercial or industrial property, or seeks federal grant money for contaminated site characterization and assessment, will need to comply with the AAI rule in order to be protected from liability under the federal Superfund law, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (“CERCLA”). At the same time, the ASTM has promulgated a new stanCERCLA provides for strict joint and several liability to dard (E1527-05) that will satisfy the new AAI rules. anyone, virtually anyone, who had anything to do with The new rule and new ASTM standard contain several a hazardous substance release or a property where con- requirements that go well beyond previous standards, intamination originated. The statute limits defenses to in- cluding: nocent landowners, bona fide prospective purchasers and • More stringent qualification requirements for contiguous property owners, but only if there was an “all environmental professionals performing due diliappropriate inquiry” into the environmental conditions gence work; of the property. CERCLA purposely did not define what • Formal certification, in writing, that all appropriconstituted an “all appropriate inquiry,” but directed ate inquiries were performed; courts to consider the several factors: (1) any specialized • Interviews with past and present owners and opknowledge or experience on the part of the defendant; erators; (2) the relationship of the purchase price to the value of • If the property is abandoned, neighboring propthe property if uncontaminated; (3) commonly known or erty owners and occupants must be interviewed; reasonably ascertainable information about the property; • Consultants must identify any data gaps in the (4) the obviousness of the presence or likely presence of final report, describe steps taken to fill the gaps, contamination at the property; and (5) the ability to deand analyze the significance of the gaps to an actect such contamination by appropriate inspection. curate and complete assessment; • Adjoining properties must be visually inspected from the adjoining property boundary, accessible rights of way, and “other vantage points”; • Historical research must cover the period back to the first site development; • The Phase I must take into account the prospective purchaser’s knowledge about the property, The standard and factors were purposely vague because Congress expected what constituted an “all appropriate inquiry” would “evolve continuously and purchasers will be held to higher standards as public awareness of the hazardous associated with hazardous substances has grown.” Such inquiries necessarily were fact intensive and, as a result, rarely could be resolved by courts at the dispositive motion stage. 4 Environmental LAW adjoining properties or the region, and any disparities between the value of the property and the purchase price; • For some properties, a prospective purchaser must assess potential impacts from controlled substances (e.g., methamphetamine labs); and, • Due diligence performed under the rule is only “useful” for six months before closing, and purchaser may use a previous Phase I report if the information was collected within the previous year so long as interviews, on-site inspections, historical reviews and lien searches are updated within 180 days before the acquisition. Even though the new AAI rule does not take effect until November 2006, environmental consultants are already adopting the standard. And while the ultimate scope of a Phase I will depend on the property at issue, it is expected that the overall quality of Phase I’s will improve as consultants expect to take a closer look at adjacent facilities. The new rule will also inject an element of uncertainty into the process (for example, making more judgement calls about how far back into the historical record to research when a site has been developed since the late 1800’s). One of the biggest unknowns about the new AAI rule is what impact it will have on the cost of Phase I’s. The EPA’s economic analysis in the draft rule issued in August 2004 estimated that the rule would add $41 to $47 to most assessments. Many of the public comments expressed skepticism that the increased costs would be that low. In the final rule, the EPA increased the estimate to $52 to $58. Some consultants in the Pacific Northwest believe the additional cost may be closer to 20 percent, which would mean an added $1,000 for an average $5,000 Phase I. Strictly speaking, the AAI rule applies only to sites where CERCLA is an issue, which would mean that petroleumimpacted sites would not be subject to the new rule. States, however, are likely to adopt similar AAI guidelines. For example, Washington, Oregon and Alaska all use some form of “all appropriate injury” language and, if adopted, this would bring petroleum-impacted sites into the AAI ambit. Equally important may be the additional time necessary to perform the added tasks under the new AAI rule. One estimate is that purchasers of Phase I’s should expect an additional week to complete the extra work required by the rule. If that proves to be the case, then it will be important for buyers and sellers to take that into account when negotiating due diligence provisions in a purchase and sale agreement. Furthermore, courts in those states look to federal statutes and court cases to interpret the state statutes. As courts have noted, what constitutes “good commercial or customary practice” varies depending on particular factual circumstances and has evolved over time. In practice, a buyer of commercial or industrial land in Washington or Oregon generally meets the “good commercial practice” by retaining a consultant to conduct an environmental site assessment consistent with the ASTM Level I standard. In fact, the 2002 amendments to CERCLA, which were the impetus for the AAI rule, set ASTM Level 1 as the interim standard. On the other hand, residential buyers rarely conduct a Level I. Instead they rely on structural inspections, which, although the customary practice, may jeopardize the owner’s ability to claim an innocent landowner defense. Accordingly, any purchaser of property should be mindful of and protect themselves from all potential environmental liability, which inevitably means conducting the most stringent due diligence required under any of the state or federal programs. The new AAI rule, thus, probably will raise the bar for all environmental site assessments. Conclusion While a new due diligence standard that squarely defines “all appropriate inquiry” is likely to provide a somewhat objective comfort for prospective purchasers of clean and contaminated properties, it is likely to come at a cost — quite literally extra dollars and time for certified environmental consultants performing pre-deal due diligence. Businesses and individuals planning to acquire real property in Washington and Oregon are wise to comply with the more stringent new federal standard. 5 Winter 2005-2006 Comparison of AAI Rule with Prior Rule Subject Environmental professionals Interviews w/ current owners and occupants Interviews with past owners and occupants Interviews with neighbors Historical review period Records of activity and use limitations Governmental records review Site inspection Contaminants of concern Prior Rule (ASTM 1527-2000) No specific requirement for educa- Final AAI Rule Specific certification/license, educa- tion, certification. tion and experience requirements. Licensing and experience. Reasonable attempt to interview key site manager and reasonable number of occupants. Not required, but must inquire about past uses when interviewing current owner and occupants. Discretionary. All obvious uses back to first obvious development or 1940, whichever is earlier. Applies to supervising professionals. Mandatory. User responsible for reporting to environmental professional. Scope limited to reasonably ascertainable land title records. Federal and state required, local at Conduct as necessary to achieve objectives and performance factors in AAI rule. Required for abandoned properties. Back to when property first contained structures or was used for residential, agricultural, industrial or governmental purposes. No requirement for who is responsible for search. Scope is liens filed or recorded under federal, state, local or tribal law. Federal, state and local records. discretion of environmental professional. Visual inspection of subject property Visual inspection of subject and required; no specific requirement to neighboring properties required. inspect neighboring properties. CERCLA hazardous substances and CERCLA hazardous substances petroleum products. Data gaps (for Brownfields Grant recipients), petroleum products and controlled substances. Discretionary, but document sources Requires identification of sources that revealed no findings. Shelf life of report Updates of specific activities recommended after 180 days. 6 consulted to address data gaps and commentary on significance of data gaps. One year, with some updates required after 180 days. Environmental LAW LET’S TWIST AGAIN ANOTHER ROUND OF THE CERCLA DANCE By Timothy R. Harmon Section 107(a) allows a party to recover all of its response costs from the responsible parties. Until quite recently, the nearly unanimous consensus was that a party could sue to recover its response costs under Section 107(a) only if it was not itself a potentially responsible party. The already convoluted rules governing who can sue to recover costs of responding to a release of hazardous materials (“response costs”) under CERCLA, the federal Superfund law, took another twist this fall. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals (which covers New York, Connecticut and Vermont), in Consolidated Edison Co v. UGI Utilities, Inc., recently broke from its own precedent and consensus rule, and held that a potentially responsible party can sue to recover its response costs under Section 107 of CERCLA. “Potentially responsible parties” (“PRP’s”) include the current owner, the owner at the time of the release, operators, arrangers and transporters. If upheld, this rule would resolve a technical, but important question in CERCLA practice. Consider a typical case. The new owner discovers his land was contaminated by past releases of hazardous materials. The new owner wants to clean up the property, but also wants the responsible parties to pay for the cleanup. Before December 2004, his course was clear under federal law. He could not sue to recover all of his response costs from the potentially responsible parties under Section 107(a) of CERCLA because he was himself a PRP. Thus, he was left with a contribution claim under Section 113. Some doubt lurked in this convenient, orderly universe, however. Section 113(f )(1) provides that any person may seek contribution from any other person liable or potentially liable under CERCLA “during or following any civil action” under CERCLA. Section 113(f )(3)(b) provides that persons who have resolved claims by the state or federal government “in an administrative or judicially approved settlement” also may sue other PRP’s for contribution. Some courts and commentators opined that the references to “civil action” and “settlement” might mean that a person could not sue for contribution under either contribution provision of Section 113 until it had been sued under CERCLA. CERCLA includes three provisions that allow private parties who have incurred necessary response costs to sue other potentially responsible parties to recover some or all of these costs: Sections 107(a), 113(f )(1) and 113(f )(3)(b). The two provisions of Section 113 create rights of contribution for persons liable or potentially liable under the federal law to recover some part of their response costs from others. A series of “equitable factors,” like length of ownership and who caused the contamination, are applied to determine the share of response costs that each party must pay. 7 Winter 2005-2006 Supreme Court’s repudiation of the contribution claim for PRP’s who had not been sued, then, must also eliminate the justification for denying these PRP’s their claim under Section 107. The Supreme Court closed that loophole in December 2004 in Cooper Industries, Inc. v. Aviall Services. Justice Thomas wrote, for a seven justice majority, that only persons who were being sued or had been sued for response costs could seek contribution from other PRP’s under Section 113(f )(1) or Section 113(f )(3)(b). As Justice Thomas expressly recognized, however, this resolution of the contribution question under Section 113 did not settle the question of who was entitled to sue under Section 107(a). If PRP’s are not permitted to sue for response costs under Section 107(a), as the pre-Cooper consensus held, then one class of persons who incur response costs is left without a remedy — PRP’s who have not been sued. Under Cooper, PRP’S seeking contribution, who had not been sued, could not bring claims under Section 113. If the existing pre-Cooper understanding survived, however, that PRP also could not sue under Section 107(a) because of its PRP status. In the typical case, therefore, in which an owner wants to recover response costs but has not been sued by another person or the government, that owner would not have a claim under CERCLA. This, of course, raises another question: Section 107(a) suits are for full recovery of response costs. If a PRP can sue under Section 107(a), did that mean it could recover all of its response costs even if it was responsible for some of the contamination in the first place? “Yes” said the Second Circuit — that is the result under Section 107(a). But, the Court continued, the other PRP (the defendant in the Section 107 lawsuit), could counterclaim for contribution under Section 113. At that point, the defendant PRP would qualify for a contribution claim under Section 113(f )(1) because it had been sued by the plaintiff PRP. The Second Circuit’s reasoning fills the policy gap that Cooper created that would encourage PRP’s to wait until they were sued to begin cleanup. Ultimately, the Supreme Court will resolve this issue as well. The court remanded Cooper to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for re-briefing and resolution of the Section 107(a) issue. Thus, the Supreme Court may have an opportunity soon to settle this issue. Until then, the situation remains cloudy, but an owner or operator of contaminated property who wants to implement a cleanup, but has not been sued, now has a reasonable argument that it can sue under Section 107(a) notwithstanding the previous consensus that PRP’s could not sue under Section 107(1). One implication of this result is that PRP’s in charge of a site might not be motivated to begin cleanup efforts until somebody sued them. This resolution seemed inconsistent with CERCLA’s policies of encouraging cleanup and imposition of cleanup costs on those responsible for them. In September of 2005, the Second Circuit Court joined a small flurry of lower courts to step up to the plate and take a swing at this dilemma. It held that a PRP may sue to recover its response costs under Section 107(a), contradicting its own precedent and the consensus among other federal courts. Whether this swing was a hit or a strike will await further developments in the other circuits and, ultimately, the United States Supreme Court. The rules under state statutes, even those modeled on the federal Superfund law, may differ. Neither the Oregon or Washington “little Superfund” statutes, for example, contain the language in Section 113 of CERCLA that limits contribution claims to those arising “during or following” a civil action or settlement. The Second Circuit reasoned that the rule barring PRP’s from suing under Section 107(a) was based on the availability of the contribution claims under Section 113. The Tim Harmon is a lawyer in our Portland Office. His practice includes environmental and other real property litigation. Tim collects first editions of modern mystery books and tin toy trains. harmont@lanepowell.com 8 Environmental LAW Environmental Indemnity: NOT NECESSARILY THE SAFETY NET PROPERTY BUYERS EXPECT By Andrew Rigel Accordingly, knowing what a “third party” liability is a crucial aspect of determining whether a real estate transaction that has potential for environmental problems is a good deal or not. Third party losses are only those damages incurred by a party unrelated to the real estate transaction. The classic third parties to a real estate transaction are local, state, or federal governmental agencies and neighboring property owners. For instance, if an underground contamination plume spreads to a neighboring property and the owner obtains a judgment against the indemnitee, the indemnitor would be responsible for the cleanup costs under a standard environmental indemnity provision in a purchase and sale contract. However, decrease in the value of the indemnitee’s property as the result of any stigma associated with the discovered contamination would not be recoverable. Environmental liabilities are a significant source of potential liability in any real estate transaction, including purchase and sales, financing, and creation of leaseholds. In today’s hot real estate climate, the risk posed by environmental contamination of a property is an often overlooked aspect of the transaction. Many buyers and sellers believe a standard environmental indemnity provision in the purchase and sale agreement covers this potential exposure. However, all environmental indemnity provisions are not created equal and could leave a property owner with unexpected losses due to contamination. First Party Losses Typically Not Covered by Indemnity Provisions. Generally, an indemnity agreement is defined as an agreement where an indemnitor, for consideration, promises to indemnify and save harmless indemnitee against liability of the indemnitee to a third person (i.e., someone other than the parties to the deal). Numerous courts from a variety of jurisdictions have held that indemnity agreements only apply liability to a third party. Even the Washington Supreme Court has opined, “Indemnity agreements are essentially agreements for contractual contribution, whereby one tortfeasor, against whom damages in favor of an injured party have been assessed, may look to another for reimbursement.” In short, environmental indemnity provisions, unless expressly stated otherwise, only cover those losses a buyer is required to pay to someone unrelated to the transaction as a consequence of the contamination. In a case from the Pennsylvania Federal District Court, the judge rejected an indemnification claim for diminution in value to property caused by environmental contamination. The property buyer in that case sought to recover damages for both response costs and diminution of the value of the property. The indemnity agreement provided, “Seller further agrees to indemnify and hold Buyer harmless from an against any and all Losses and Expenses suffered or incurred by Buyer as the result of environmental contamination . . . .” The contract defined “Loss and Expense” to include “any and all losses, costs and expenses.” The court rejected the buyer’s contention that this broad definition encompassed diminution in property value associated with the environmental con9 Winter 2005-2006 the right to do the work in order to control costs. If this is the case, it needs to be stated clearly in the agreement • Duration of the Indemnity — The parties need to negotiate the length of an indemnity, which is extremely important with environmental conditions that can linger for many years. Again, buyer and seller will have conflicting objectives when it comes to indemnity duration. Successful negotiation of the indemnity terms will require input from the environmental consultants and governmental agencies, who can estimate the duration of a particular risk. If the indemnity is limited, then the parties should clearly state whether the duration starts at discovery or at completion of the cleanup • Financial Guarantees — Indemnities are only as valuable as the asset sheet of the party giving the indemnity. If the party granting the indemnity is financially suspect, the other party may need to collateralize the indemnity obligation with some form of security, whether it is a bond, an escrow account, or some form of environmental insurance. • Allocate Risks in the Purchase Price Whenever Possible – The most effective way of allocating environmental risk is to quantify the risk and either add it or deduct it from the purchase price. Consultants are sufficiently sophisticated, and governmental cleanup requirements are established and clear enough that it is much easier now to quantify risk. • Environmental Escrows — Environmental escrows are becoming more popular, but it is questionable whether they are an effective resolution to the issue. These escrow accounts are usually inefficient and lead to more contention than benefit. First, one party always has an incentive to spend the money. Second, consulting firms have an even clearer incentive to spend the money. Third, the other party may want to minimize expenditures in hopes of getting money back at the end of the escrow term. Together, these competing interests result in constant tension and second-guessing between the parties. Fourth, it requires the two parties to continue an unnecessary and potentially difficult or costly relationship long after a deal is completed. Fifth, it is fundamentally inefficient to leave the money in an escrow account rather than having it used to build the business, add improvements, acquire more property or invest. tamination. The court clearly stated, “indemnity agreements do not cover losses in value, but only costs payable to third parties.” Conversely, some California courts have been more receptive to arguments that indemnification provisions encompass more than just third-party losses. In one such case, the California Court of Appeals held that an opposite presumption applies and unless the contract specifically limits the losses to those arising from third-party lawsuits then all losses, including those incurred by the buyer alone, are recoverable. However, California’s interpretation is definitely a minority position. How to Get the Most Protection From an Environmental Indemnity Provision. The following is a list of issues that a should at least be considered when negotiating an environmental indemnity provision in a real estate purchase and sale agreement: • Express Language — An environmental indemnity must be in writing and must clearly state the applicable terms. Even where a purchase and sale document or lease contains a general indemnity, the parties should use a second environmental indemnity that addresses carefully defined environmental liabilities. • Address All Costs — There are several cost categories that may not fit into the typical definition of “site cleanup.” They include assessment costs, post-remediation monitoring, agency negotiations, site access issues and general legal fees. These should be dealt with up front in the indemnity language. Most importantly, if it is expected that the indemnity will include more than just third-party losses, then it must be expressly stated in the agreement that second party losses such as diminution in value and holding costs are included. • Performance of the Cleanup — A good environmental indemnity not only allocates liability but also details how assessment and cleanup work will be performed, by whom, and on what timetable. A buyer and seller typically have divergent goals when it comes to cleanup. For example, if a seller gives an environmental indemnity, he or she will want to maintain control over when and how claims are handled and cleanup work is done. The buyer, on the other hand, will want to spend as much money and effort as possible to ensure the property is clean. Often the party giving the indemnity will want to maintain Andrew Rigel is an attorney in our Seattle office. His practice focuses on environmental and real estate related matters. Andrew is a competitive mountain bike racer in his spare time. rigela@lanepowell.com 10 Providing Legal Counsel on Environmental Issues environmental attorneys offices Amster, Glenn SEATTLE amsterg@lanepowell.com suite 4100 1420 fifth avenue seattle, wa 98101-2338 206.223.7000 Davis, Robert davisr@lanepowell.com PORTLAND Degginger, Grant deggingerg@lanepowell.com suite 2100 601 sw second avenue portland, or 97204-3158 503.778.2100 Harmon, Timothy harmont@lanepowell.com ANCHORAGE Maloney, Robert maloneyr@lanepowell.com suite 301 301 west northern lights boulevard anchorage, ak 99503-2648 907.277.9511 Nesteroff, Michael nesteroffm@lanepowell.com OLYMPIA Pyle, Don (CHAIR) pyled@lanepowell.com suite 360 111 market street ne olympia, wa 98501 360.754.6001 Rigel, Andrew rigela@lanepowell.com LONDON Williams, Karen williamsk@lanepowell.com office 2.24 148 leadenhall street london ec3v 4qt uk 011.44.020.7645.8210 © 2005 lane powell pc Editor’s Note: We provide Environs as a service to our clients, colleagues and friends. It is intended to be a source of general information, not an opinion or legal advice on any specific situation, and does not create an attorney-client relationship with our readers. If you would like more information regarding whether we may assist you in any particular matter, please contact one of our lawyers, using care not to provide us any confidential information until we have notified you in writing that there are no conflicts of interest and that we have agreed to represent you on the specific matter that is the subject of your inquiry. Mike Nesteroff, Editor w w w . l a n e p o w e l l . c o m