Document 13191877

advertisement

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR NUMERICAL METHODS IN ENGINEERING

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

Published online 4 April 2013 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/nme.4482

A posteriori analysis and adaptive error control for operator

decomposition solution of coupled semilinear elliptic systems

V. Carey1 , D. Estep2, * ,† and S. Tavener1

1 Department

of Mathematics, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

of Statistics, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

2 Department

SUMMARY

In this paper, we develop an a posteriori error analysis for operator decomposition iteration methods

applied to systems of coupled semilinear elliptic problems. The goal is to compute accurate error estimates

that account for the combined effects arising from numerical approximation (discretization) and operator

decomposition iteration. In an earlier paper, we considered ‘triangular’ systems that can be solved without iteration. In contrast, operator decomposition iterative methods for fully coupled systems involve an

iterative solution technique. We construct an error estimate for the numerical approximation error that

specifically addresses the propagation of error between iterates and provide a computable estimate for

the iteration error arising because of the decomposition of the operator. Finally, we develop an adaptive

discretization strategy to systematically reduce the discretization error. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley &

Sons, Ltd.

Received 25 November 2011; Revised 2 November 2012; Accepted 16 January 2013

KEY WORDS:

a posteriori error estimates; adjoint problem; dual problem; error estimates; finite

element method; generalized Green’s function; operator splitting; operator decomposition;

coupled problems

1. INTRODUCTION

We develop an a posteriori error analysis framework for operator decomposition iteration methods

applied to systems of coupled semilinear elliptic problems of the form,

L1 .x, u1 , Du1 , D 2 u1 / D f1 .x, u1 , u2 , Du2 , u3 , Du3 , , un , Dun /,

2

L2 .x, u2 , Du2 , D u2 / D f2 .x, u1 , Du1 , u2 , u3 , Du3 , , un , Dun /,

..

.

x 2 ,

x 2 ,

Ln .x, un , Dun , D 2 un / D fn .x, u1 , Du1 , u2 , Du2 , , un1 , Dun1 , un /,

(1.1)

x 2 ,

where Dv and D 2 v are the first and second-order derivative operators, ¹Li , i D 1, , nº is

a collection of linear uniformly coercive, elliptic differential operators, ¹fi , i D 1, , nº is a

collection of differentiable functions, is a convex polygonal domain with boundary @, and

Equation (1.1) is supplied with suitable boundary conditions on @. We note that the coupling in

the system occurs through the right-hand sides only. We assume that Equation (1.1) satisfies suitable

conditions to guarantee a solution in WQ 21 ./ in weak form, for example, generic conditions involve

a uniform bound on the derivatives of f . An extension of our analysis to fully nonlinear elliptic

systems is straightforward but tedious in detail, for example, involving a messy linearization of the

diffusion operator.

*Correspondence to: D. Estep, Department of Statistics, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523.

† E-mail: estep@stat.colostate.edu

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

827

Interest in coupled physics problems and their solution arises in many fields. The Oregonator

model for the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction system,

@u1

u1 q

D1 r 2 u1 D u1 u21 f u2

,

@t

u1 C q

@u2

D 2 r 2 u 2 D u1 u 2 ,

@t

is an example of an important time-dependent coupled semilinear system. To consider waves

traveling with permanent form with velocity c in the x-direction, we make the ansatz, ui .t , x, y/ D

ui ., y/, i D 1, 2, where D x ct . Upon substitution, we obtain the stationary coupled semilinear

elliptic system,

@u1

u1 q

C u1 u21 f u2

,

@

u1 C q

@u2

D2 r2 u2 D c

C u1 u2 ,

@

D1 r2 u1 D c

where r2 ./ D @2 ./=@2 C @2 ./=@y 2 .

In many practical situations, coupled systems of partial differential equations are decomposed

into individual physics components, each of which is solved with a code specialized to the

particular type of physics, whereas the solution is obtained by various forms of iteration and/or

operator decomposition. Such approaches introduce new forms of instability and new sources of

error that must be included in an a posteriori error analysis, see [2] for an overview.

In this paper, we assume that the system (1.1) is solved by an operator decomposition approach

that involves iteratively solving the ordered sequence of problems,

Li x, ui , Dui , D2 ui D fi .x, uO 1 , D uO 1 , uO 2 , D uO 2 , , uO i 1 , D uO i 1 , ui , uO i C1 , D uO i C1 , , uO n , D uO n / ,

which are obtained by substituting solutions uO j for j ¤ i computed in a previous step in the

equations in Equation (1.1) and then solving for ui . Theoretically, the sequence is iterated until

convergence (if it does converge), whereas in practice, a finite number of iterations is used.

In [1], we present an a posteriori error analysis for operator decomposition methods applied to

systems of elliptic equations that had an ‘upper triangular’ form, so that one iteration through the

system produces the solution. That analysis accounts for the following:

errors arising from the discretization of each component elliptic problem,

the transfer of error between the component elliptic problems,

errors resulting from using different discretizations for the component elliptic problems.

In a fully coupled system (1.1), we need to iterate through the components until, hopefully, the

iteration converges. In addition to the errors affecting the solution of a triangular system, the a

posteriori error analysis now must also account for the following:

the effects of finite iteration,

the transfer of errors between iterations.

These two effects are the focus of the analysis in this paper. The results in this paper can be combined

with the full analysis of [1] to treat all five of these effects in one estimate.

We let U ¹kº be a numerical approximation obtained by iterating numerical discretizations of the

differential equations k times. To carry out the a posteriori error analysis, we decompose the error

as

u U ¹kº D

u ƒ‚

u¹kº

„

…

analytic iteration error

¹kº

¹kº

C„

u¹kº ƒ‚

U ¹kº

…DE Ce ,

(1.2)

numerical error

where u¹kº is the analytic solution obtained at iteration k by solving the sequence of iterated

differential equations exactly. We estimate these two components separately. This decomposition

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

828

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

is motivated by the observation that the iterative discrete approximation is a consistent numerical

solution of the analytic iterative problem. One consequence is that this simplifies the definition

of an appropriate adjoint for the error analysis. Namely, we use the adjoint associated with the

solution operator of the sequence of iterated component problems. This is a complex operator that

can itself be defined through an iterated sequence of adjoint problems to the individual components.

In practical terms, we can compute the resulting a posteriori error estimate without forming and

solving the adjoint for the fully coupled system. Solving the full adjoint of the coupled system is

computationally impractical in situations in which operator decomposition iteration is used to solve

the forward problem.

The main focus of this paper is a posteriori error estimation of the numerical error e ¹kº . At the

kth step of an iterative solution process and for a given quantity of interest, the analysis accounts

for the following:

the numerical errors made at the current iteration,

the numerical errors made at all previous iterations,

the error due to the iterative approximation.

For clarity of exposition, we do not include treatment of the errors arising from the use of different

discretizations for different components. Such effects are already treated in the earlier paper [1], and

those results can be combined with the results in this paper in a straightforward way.

To obtain a full a posteriori error estimate of the error u U ¹kº , we have to also estimate the

analytic iteration error E ¹kº . The difficulty is that this involves the true solution and an ‘iterative’

true solution, both of which are unknown. However, for a fixed space mesh, we can adapt the classical asymptotic estimator for the error in an iterative approximation to this situation. Lacking such

an estimate, the a posteriori error estimate of e ¹kº that provides an estimate of the full error provided

the numerical error that dominates the iteration error, that is, in the limit of increasing iterations.

When we have estimates for E ¹kº and e ¹kº , we can then derive a generalized adaptive algorithm

that adjusts both the number of iterations and the level of discretization in each component to achieve

a desired accuracy with relative computational efficiency.

This work can be differentiated from a number of previous analyses of nonlinear problems, for

example, see references in [3–9], in concentrating on new issues arising in fully coupled systems

and dealing explicitly with the effects of operator decomposition and finite iteration. Ignoring the

coupling involved in treating a system, for example, simply estimating the error in each component in isolation, can lead to catastrophic failure of the error estimates. See Example 3.2 of [1] and

Example 4.1 as follows.

The outline of the paper is as follows. To explain the ideas behind the definition of an appropriate

adjoint operator for the iterated system and the a posteriori error analysis, we begin by deriving

an a posteriori error estimate for the iterated solution of a finite dimensional algebraic systems in

Section 2. This derivation contains the main ideas without the complications of differential equation

discretization errors and moreover makes it easy to construct several illuminating examples. We

then turn to the analysis of coupled semilinear elliptic problems in Section 3. We present results for

three particular classes of operator decomposition iteration techniques, namely, block Jacobi, block

Gauss–Seidel, and relaxed block Jacobi. In Section 4, we give numerical examples of different

aspects of the error estimation framework, concluding with an adaptive algorithm that adaptively

refines both the computational mesh and the operator decomposition iteration to converge to an

accurate solution.

2. PRELIMINARY EXAMPLE: ITERATIVE SOLUTION OF ALGEBRAIC SYSTEMS

To explain the construction of an appropriate adjoint operator for an iterated solution approach and

the idea that the numerical error of the current iterate is affected by errors introduced at all previous

iterations, we first present the analysis in the context of finite dimensional algebraic systems. We

begin with a linear problem and then treat a nonlinear problem.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

829

2.1. Estimating the numerical error for linear algebraic systems

We consider the solution of

Aw D b.

We construct an iterative solution method using a matrix decomposition of A of the form

A D D C C,

where we assume that D is invertible. The solution procedure uses the observation that

.D C C/w D b ) Dw D b Cw

and solves

w ¹0º D 0,

Dw ¹i º D b Cw ¹i 1º , i D 1, 2, : : : , k

³

.

(2.1)

We assume that the iterative scheme converges, which depends on the spectral radius of D1 C.

At each stage of the iterative process, we compute a numerical solution W ¹i º w ¹i º . Our goal

is to estimate the error in a quantity of interest that is representable as a linear functional of the

solution, that is, a quantity of interest of the form .w, /, at any iterate i. We write this error as

.w W ¹i º , / D .w w ¹i º , / C .w ¹i º W ¹i º , / D E ¹i º C e ¹i º .

ƒ‚

…

ƒ‚

…

„

„

analytic iteration error

numerical error

Here, a superscript in braces ¹i º indicates variables corresponding to forward iteration i. Let k be

the total number of forward iterations performed. Later, we use a superscript in square brackets Œj to denote the adjoint problem corresponding to forward iteration i D k j C 1.

2.1.1. Estimation of the numerical error e ¹i º . Because the previous iterate enters as data, the numerical error e ¹i º depends not only upon the numerical error made at the ith iteration, but also on

the numerical errors made at previous iterations. Hence, we need to estimate the effects of these

‘inherited errors’.

Given W ¹0º D 0, we compute the sequence of approximate solutions W ¹i º of Equation (2.1),

i D 1, : : : , k, as

DW ¹i º D b CW ¹i 1º .

(2.2)

Theorem 2.1

The error in the quantity of interest can be estimated as,

k

X

¹kº

e ,

D

R W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º ,

(2.3)

j D1

where the adjoint problems are defined,

D> Œ1 D

,

D> Œj D C> Œj 1 ,

(2.4)

j D 2, : : : , k,

(2.5)

and

R.W ¹kº , Œj I W ¹mº / D .b CW ¹mº DW ¹kº , Œj /.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

(2.6)

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

830

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

Note that the adjoint problems (2.4)–(2.5) involve the simpler matrix associated with the iterative

scheme, not the full adjoint of the original matrix A. To emphasize the role of the error in the most

recent (kth) iteration, we may write

.e

¹kº

, / D .W

¹kº

Œ1

, IW

¹k1º

/C

k

X

R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /.

(2.7)

j D2

Also, note that the sequence of coupled adjoint problems (2.5) yields the natural adjoint to the solution operator associated with the iterative method. We emphasize this point by numbering the adjoint

problems in the reverse order to the forward iteration number.

Proof

The estimates of the numerical error after k iterations is

.e ¹kº , / D .w ¹kº W ¹kº , D> Œ1 / D .D.w ¹kº W ¹kº /, Œ1 /

D .b Cw ¹k1º DW ¹kº , Œ1 /

D .b CW ¹k1º DW ¹kº , Œ1 / .C.w ¹k1º W ¹k1º /, Œ1 /

D R.W ¹kº , Œ1 I W ¹k1º / .C.w ¹k1º W ¹k1º /, Œ1 /.

(2.8)

The first term on the right of Equation (2.8) is the usual error estimate depending on the computable residual of W ¹kº and the corresponding adjoint solution. The second term on the right of

Equation (2.8) estimates the contribution to the error of W ¹kº resulting from the error inherited from

the approximation W ¹k1º to w ¹k1º . This inherited error term can be expressed as the error in a

new quantity of interest at the previous iteration by noting that

.C.w ¹k1º W ¹k1º /, Œ1 / D .w ¹k1º W ¹k1º , C> Œ1 / D .e ¹k1º , C> Œ1 /.

To estimate the error in this new quantity of interest, we solve the new adjoint problem

D> Œ2 D C> Œ1 ,

to obtain

.e ¹k1º , C> Œ1 / D .w ¹k1º W ¹k1º , C> Œ1 / D .w ¹k1º W ¹k1º , D> Œ2 /

D .b Cw ¹k2º DW ¹k1º , Œ2 /

D .b CW ¹k2º DW ¹k1º , Œ2 / .C.w ¹k2º W ¹k2º /, Œ2 /

D R.W ¹k1º , Œ2 I W ¹k2º / .C.w ¹k2º W ¹k2º /, Œ2 /.

Continuing in this fashion, we see that the desired estimate of the error in the quantity of interest

.e ¹kº , / after k iterations requires the solution of Equation (2.4) and the recursive solution of an

ordered sequence of .k 1/ adjoint problems

D> Œj D C> Œj 1 ,

j D 2, : : : , k,

and

.e ¹kº , / D

k

X

R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /.

j D1

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

831

2.1.2. The decay of influence of contributions from early iterations. To estimate the numerical error

in the quantity of interest after k iterations, we nominally need to solve k adjoint problems. (One

of the form (2.4) and k 1 of the form (2.5)). Each of these is solvable, but the number can be

significant. The sequence of adjoint problems has the form

Œj C1 D .D> C> /j Œ1 ,

j D 1, : : : , k 1.

By noting that

D1 .CD1 /D D D1 C,

we see that D1 C, CD1 , and D> C> all have the same spectral radius. For the forward iteration

to converge the matrix product, D1 C must have a spectral radius smaller than one. This means that

we expect that

ŒmlC1 D .D> C> /ml Œ1 ! 0

for fixed l as m ! 1. This suggests that we might obtain a reasonable approximation

.e

¹kº

, /

l

X

R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /

(2.9)

j D1

for some small l > 1. The more rapid the convergence of the forward iteration (the smaller the

spectral radius of D1 C), the smaller the value of l required.

2.1.3. Estimating the iterative error E ¹kº . We begin with a classic estimate for the iteration error

on the basis of extrapolation. We define J ./ D ., / and denote E ¹kº D w w ¹kº . Assuming a

linearly convergent sequence J .E ¹i º /, the classic asymptotic argument yields,

J .E ¹kº / .J .w ¹kº / J .w ¹k1º //2

.

J .w ¹kº / J .w ¹k1º / .J .w ¹k1º / J .w ¹k2º //

This estimate is not directly computable, however, the right-hand side can be further estimated as,

J .E ¹kº / .J .e ¹kº / J .e ¹k1º / C J .W ¹kº / J .W ¹k1º //2

.

J .e ¹kº / 2J .e ¹k1º / C J .e ¹k2º / C J .W ¹kº / 2J .W ¹k1º / C J .W ¹k2º /

(2.10)

The expression (2.10) can be estimated using the a posteriori error estimate, but this is expensive.

We may derive another estimate by assuming the numerical error is higher-order than the iteration

error, to obtain

J .E ¹kº / .J .W ¹kº / J .W ¹k1º //2

.

J .W ¹kº / 2J .W ¹k1º / C J .W ¹k2º /

(2.11)

The approximation (2.11) may, however, lead to inaccurate estimates when the iteration and

numerical errors are of comparable size.

2.1.4. Numerical example. We construct a diagonally dominant, symmetric 20 20 matrix A D

20I C R, where R is a random 20 20 matrix with Frobenius norm less than or equal to one.

We decompose A into two matrices D and C, A D D C C, where D contains only the diagonal

entries of A. We then solve Aw D b via operator decomposition iteration with the iteration given by

Equation (2.1) where the solution at each iteration is obtained using conjugate gradient solver with

a tolerance of 104 . The iteration terminates when kW ¹i º W ¹i 1º k < 108 that is accomplished

in 11 iterations. We then solve (to within round-off) the sequence of 11 adjoint problems defined

recursively by Equations (2.4) and (2.5) for quantity of interest u20 , that is, with D Œ1 D D e20

(where e20 is the unit vector with a single nonzero entry in the 20th row) and compute each of the

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

832

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

Table I. Error components for W ¹11º for example 2.1.4.

Total error

jw ¹20º W ¹20º j

Iteration error

jw w ¹11º j

Numerical error

jw ¹11º W ¹11º j

Primary numerical error

jR.W ¹11º , Œ1 I W ¹10º /j

7.43823 105

2.2234 1011

7.4382 105

9.465 105

terms in the error representation formula (2.3) for k D 1, : : : , 11. We call the first term in this sum

the primary numerical error (Table I).

¹11º

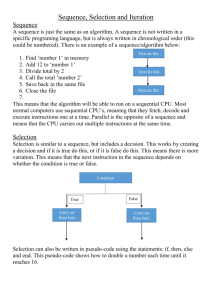

The expected decay of the contributions to the error e20

that are inherited from previous

iterations is illustrated in Figure 1.

2.2. Estimating the numerical error for nonlinear algebraic systems

Nonlinearity introduces additional complexities for defining an adjoint problem. We solve the

nonlinear equation

Aw D f .w/

(2.12)

Aw ¹i º D f .w ¹i 1º /, i D 1, : : : , k

(2.13)

by successive approximation

with W ¹0º D 0. Given W ¹0º D 0, we compute the sequence of numerical approximations W ¹i º for

i D 1, : : : , k as

AW ¹i º D f .W ¹i 1º /.

(2.14)

Theorem 2.2

The error in a quantity of interest is estimated as,

.e ¹kº , / D

k

X

R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /,

(2.15)

j D1

where the adjoint problems are defined,

A> Œ1 D ,

A> Œj D Lf .w ¹kj º , W ¹kj º /> Œj 1 ,

³

j D 2, : : : , k

,

(2.16)

−3

−4

−5

log(hist. err)

−6

−7

−8

−9

−10

−11

−12

−13

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

History Term (j)

Figure 1. Individual ‘history’ terms R.W ¹11j C1º , Œj I W ¹11j º / for example 2.1.4 illustrating the

¹11º

with index j .

expected decay in contributions to e20

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

833

using the linearization Lf .v, V / defined,

Z

1

Lf .v, V / D

J.sv C .1 s/V / ds,

0

where J./ is the Jacobian of f .

Proof

The steps are similar to the previous arguments,

.e ¹kº , / D .e ¹kº , A> Œ1 /

D .Aw ¹kº AW ¹kº , Œ1 /

D .f .w ¹k1º / AW ¹kº , Œ1 /

D .f .W ¹k1º / AW ¹kº , Œ1 / C .f .w ¹k1º / f .W ¹k1º /, Œ1 /

D R.W ¹kº , Œ1 I W ¹k1º / C .Lf .w ¹k1º , W ¹k1º /e ¹k1º , Œ1 /

D R.W ¹kº , Œ1 I W ¹k1º / C .e ¹k1º , Lf .w ¹k1º , W ¹k1º /> Œ1 /

D R.W ¹kº , Œ1 I W ¹k1º / C .e ¹k1º , A> Œ2 /

..

.

D

k

X

R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /.

j D1

2.2.1. Linearization and adjoints for nonlinear adjoints. In general, there are multiple ways to

define an adjoint to a nonlinear operator [10]. Choosing a suitable definition is highly dependent on

the purpose for which the adjoint is intended. For a perturbation or error analysis, one systematic

way to define an adjoint is based on linearization. Consider an approximate solution W w of

Equation (2.12) computed without iteration, and define the residual

R.W / D AW f .W /.

The standard analysis begins

A.w W / .f .w/ f .W // D R.W /.

The integral mean value theorem yields

Z

f .w/ f .W / D Lf .w W / D

1

J.sw C .1 s/W / ds .w W /.

0

Introducing the formal adjoint problem

.A Lf / D

leads to the a posteriori error estimate

.w W , / D .R.W /, /.

In practice, the linearization Lf cannot be computed and is approximated as,

Z 1

Z 1

J.sv C .1 s/V / ds J.sV C .1 s/V / ds D J.V /.

Lf .v, V / D

0

(2.17)

0

The approximation in the linearization may certainly affect the accuracy of the a posteriori error

estimate. However, the effect can be bounded a priori under regularity assumptions on the problem, that is, the second derivatives of f are uniformly bounded in a compact region containing

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

834

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

the true solution, analytic iterative solutions, and iterative numerical solutions, and assuming that

the iteration converges and the approximations are sufficiently close to the true solution. In particular, W should be sufficiently close to w and R.W / should be sufficiently small. In practice, the

approximation (2.17) works well in many situations in the sense that the linearization error has relatively insignificant effect on accuracy of the estimate when the numerical solutions are reasonably

accurate. Perhaps, more importantly, catastrophic failure of the a posteriori error estimate, that is an

estimate that is low when the actual error is large, is relatively difficult to manage. See [8] for a discussion of this point for systems of reaction-diffusion equations and an example where catastrophic

failure is created.

However, this simple approach to defining an adjoint operator when operator decomposition iteration is used can fail. The difficulty is that an iterative solution W ¹i º is actually solving a problem

that is significantly different than the original problem. See [2] for a discussion of this point.

The approach to define an adjoint for Theorem 2.2 avoids this issue by constructing a global

adjoint for the iterative solution operator via a sequence of coupled adjoints for each individual component problem obtained by linearization between the iterative analytic w ¹i º and iterative numeric

W ¹i º solutions. The effects of this ‘local’ linearization can be controlled under local regularity and

convergence assumptions as described earlier. In practice,

A> Œj D Lf .w ¹kj º , W ¹kj º /> Œj 1

is approximated by

A> Q Œj D J.W ¹kj º /> Q Œj 1

(2.18)

for j D 2, : : : , k.

The price of the indicated approach to defining an adjoint for the iterated solution operator is that

the a posteriori error estimates accounts only for the numerical error e ¹i º and leaves the analytic

iterative error E ¹i º remaining to be estimated. We adapt the estimate discussed in Section 2.1.3.

2.2.2. Numerical examples. We now consider three new situations that may arise for nonlinearly

coupled problems. Let

Aw D f .w/,

where

1

3 1

0

0

3

0

0 C

B 1

AD@

0

0

3 1 A

0

0 1

3

0

0

and

1

exp.ˇ.w3 0.4/2 /

B exp.ˇ.w4 0.6/2 / C

C

f .w/ D ˛ B

@ exp.ˇ.w1 0.5/2 / A ,

exp.ˇ.w2 0.3/2 /

and let the quantity of interest be the value of w2 . In all cases, a high accuracy reference solution w

was generated using Newton’s method with a tolerance of 1012 , whereas we also computed high

accuracy reference iterative solutions w ¹i º to full precision. To compare with estimates employing

the adjoint problem associated with the original system, the ‘global’ adjoint corresponding to the

full (i.e. nondecomposed) problem was also constructed and solved, and error estimates based on

the adjoint to the full problem are reported in the following examples. We set,

R.W , / is the error estimate on the basis of the exact linearization of the global adjoint

problem, and

Q is the error estimates on the basis of the approximate linearization of the global

R.W , /

adjoint problem.

The approximate solutions W ¹i º were computed by rounding to the sixth decimal place. All adjoint

solutions were computed with full precision. In each case, we estimated the iteration error using

Equation (2.11).

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

835

Cancelation between iteration and numerical error. Let ˛ D 1, ˇ D 10, and i D 40. The iteration

converges after 40 iterations when the norm of the residual is less than 104 . Results are provided

in Table II.

Notice that the adjoint to the coupled problem gives an excellent estimate of the error, yielding

four significant figures even when using the approximate linearization. What is obscured is the cancelation that occurs between the iteration and numerical error. The methods developed here enable

the iteration and numerical errors to be estimated separately, and this is important when constructing

adaptive algorithms. However, the iteration error estimate is polluted by the numerical error in U ¹kº .

The partial sums of the history terms are plotted in Figure 2 where expected decay of history error

contributions can be observed.

The effect of linearization error. Let ˛ D 2, ˇ D 8, i D 100. In this example, although w ¹kº and

W ¹kº approach have the same fixed point, they both do so in a nonmonotonic fashion. This produces

significant differences between Lf .w ¹kj º , W ¹kj º /> and J.W ¹kj º /> (see Equations (2.16) and

(2.18), respectively) and consequently significant differences in the corresponding adjoint solutions

and Q (Table III). Results are provided in Table IV where the practical numerical error estimate is

seen to be completely inaccurate.

To obtain an estimate of how rapidly the adjoint solutions and Q can diverge, we see from

Equations (2.16) and (2.18) that

Œj Q Œj D A> Lf .W ¹kj º , w ¹kj º /> Œj 1 J.W ¹kj º /> Q Œj 1

>

A> Lf .W ¹kj º , w ¹kj º / J.W ¹kj º / Œj 1 I

Table II. Error components for example 2.2.2. Note the cancellation of errors between the iteration and

numerical error. (R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º / R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj /.)

Error

jw2 W2 j

1.1102276 106

Numerical error

¹kº

¹kº

w2 W2

Estimated error

R.W , /

Practical error

Q

R.W , /

Iteration error

¹kº

w2 w2

1.1102276 106

1.10983 106

2.55547 106

Pract. numerical error

P

¹kj C1º , Q Œj /

j R.W

Est. iteration error

1.44592 106

6.6554 106

Est. numerical error

¹kj C1º , Œj /

j R.W

P

1.44524 106

1.44524 106

2.5

x 10−6

N.I. Error Estimate

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

−0.5

−1

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

# of History Terms

Figure 2. Numerical error estimate

Pm

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

j D1

R.U ¹kj C1º , Œj I U ¹kj º / including m ‘history’ terms for

example 2.2.2.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

836

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

Table III. Error components for example 2.2.2, with R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj / R.W ¹kj C1º ,

Œj I W ¹kj º /.

Error

w2 W2

Estimated error

R.W , /

0.048166

Numerical error

¹kº

¹kº

w2 W2

Practical error

R W , Q

Iteration error

¹kº

w2 w2

0.048166

7.06634

0.050168

Est. numerical error

P

¹j kº , Œj /

j R.W

Pract. numerical error

P

¹j kº , Q Œj /

j R.W

Est. iteration error

0.002002

3.58 106

0.04568

0.002002

Table IV. Error components for example 2.2.2. (R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj / R.W ¹kj C1º , Œj I W ¹kj º /.

Error

jw2 W2 j

0.0999965

Estimated error

R.W , /

Practical error

R W , Q

Iteration error

¹kº

w2 w2

0.0999965

0.076506

0.0999963

Numerical error

¹kº

¹kº

w2 W2

Est. numerical error

P

¹j kº , Œj /

j R.W

Pract. numerical error

P

¹j kº , Q Œj j R W

Est. iteration error

1.8524 106

1.8524 106

1.8530 106

0.18273

1.5

1

0.5

0

−0.5

−1

0

u−U

spec(inv(A)(LF−DF))

20

40

60

80

100

120

Iteration

Figure 3. Differences between w ¹kº and W ¹kº and the spectral radius of A> .Lf .w, W / J.W //> for

example 2.2.2.

>

so, the spectral radius of A> Lf .W ¹kj º , w ¹kj º / J.W ¹kj º / can be considered as an amplification factor to explain the exponential accumulation of linearization error in the history error

estimate (Figure 3).

Divergent iteration. Let ˛ D 2, ˇ D 7, and k D 100. The iteration fails to converge, but all error

estimates in Table IV are well-behaved but exhibit significant linearization error. Not surprisingly,

because the iteration error estimate assumes a convergent iteration, the estimate of the iteration error

is poor. However, despite the fact that the iteration is divergent, the estimate of the numerical error

is accurate, and the effectivity ratio (defined as the ratio of the error estimate to the true error) shown

in Figure 4 improves as the number of history terms is increased, although the practical numerical

error estimate is affected by errors by to linearization.

2.2.3. Discussion. An interesting case is the situation in which the numerical error is much higher

than the stopping criterion (say round U to the third decimal place), but the corresponding theoretical iteration converges quickly. The computation does not converge because of the numerical error,

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

837

3.5

Effectivity Index

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

20

40

60

80

100

# of History Terms

P

¹kj C1º

Figure 4. Effectivity ratio for the numerical error estimate m

, Œj I W ¹kj º / including

j D1 R.W

m ‘history’ terms for example 2.2.2.

but the quick computation of a few history terms leads to an exact estimate of the numerical error.

See Section 4.2.4 for an adaptive solution to a similar problem.

In all three examples, the global adjoints are not diagonally dominant or symmetric positive dominant. But even when the operator decomposition iteration solution for the global adjoint (e.g. a

‘Jacobi’ iteration) does not converge, the a posteriori error analysis still provides meaningful error

estimates. See Section 4.2.2 for more discussion.

3. ANALYSIS FOR SEMILINEAR ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

For ease of presentation, we focus the analysis on a two component fully coupled elliptic system of

the form

r a1 .x/ru1 C b1 .x/ ru1 C c1 .x/u1 D f1 .x, u1 , u2 , Du2 /,

r a2 .x/ru2 C b2 .x/ ru2 C c2 .x/u2 D f2 .x, u1 , Du1 , u2 /,

u1 D u2 D 0, x 2 @,

x 2 ,

x 2 ,

(3.1)

where is a convex polygonal domain in Ri , i D 1, 2, 3, with boundary @, and we assume that

ai , bi , ci , fi , i D 1, 2 are sufficiently smooth to establish optimal order a priori convergence for the

finite element method computed without operator decomposition iteration.

The weak formulation of Equation (3.1) is the following: find um 2 WQ 21 ./ satisfying

A1 .u1 , v1 / D .f1 .x, u1 , u2 , Du2 /, v1 /,

A2 .u2 , v2 / D .f2 .x, u1 , Du1 , u2 /, v2 /,

8v1 2 WQ 21 ./,

8v2 2 WQ 21 ./,

(3.2)

where

A1 .u1 , v1 / .a1 ru1 , rv1 / C .b1 ru1 , v1 / C .c1 u1 , v1 /,

A2 .u2 , v2 / .a2 ru2 , rv2 / C .b2 ru2 , v2 / C .c2 u2 , v2 /,

are assumed to be coercive bilinear forms on and WQ pn ./ represents the subspace of Wpn ./ with

zero trace on @.

If we were numerically solving Equation (3.2) without operator decomposition iteration, then

we would introduce conforming discretizations Sh,m ./ and solve the discretized system: find

Um 2 Sh,m ./ satisfying

A1 .U1 , 1 / D .f1 .x, U1 , U2 , DU2 /, 1 /,

A2 .U2 , 2 / D .f2 .x, U1 , DU1 , U2 /, 2 /,

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

81 2 Sh,m ./,

82 2 Sh,m ./.

(3.3)

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

838

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

3.1. Analysis of operator decomposition iteration solutions

We analyze three different operator decomposition iterations for producing numerical approximations of Equation (3.1). We recall that we decompose the error as in Equation (1.2), that is,

u U ¹kº D

u ƒ‚

u¹kº

„

…

analytic iteration error

¹kº

¹kº

C„

u¹kº ƒ‚

U ¹kº

…DE Ce ,

numerical error

where u¹kº respectively U ¹kº are the analytic and discrete solutions obtained by the particular iteration approach under consideration. The a posteriori error analysis is for the numerical error e ¹kº .

We estimate the analytic iteration error E ¹kº by a natural application of the estimates discussed in

Section 2.1.3.

For simplicity of presentation, we assume the quantity of interest is given as a linear

functional

of

¹kº

>

the second solution component, determined by D .0, 2 / , that is, we estimate e2 , 2 . For

notational convenience and to be consistent with [1], we abbreviate the weak residual of a solution

component,

Rm ., I / D .fm ./, / Am ., /,

m D 1, 2.

3.1.1. Block Jacobi iteration. We first consider a block Jacobi operator decomposition iterative

approach to the solution of the semilinear elliptic system (3.1).

Theorem 3.1

The representation formula for the numerical error e ¹kº is

X

X

R2 U2¹kj C1º , 2Œj I U1¹kj º C

.e ¹kº , / D

j 6k, j odd

R1 U1¹kj C1º , 1Œj I U2¹kj º ,

j 6k, j even

(3.4)

where the corresponding adjoint problems are

A2 , 2Œj D , 2Œj ,

A1 , 1Œj D , 1Œj ,

8 2 WQ 21 ./,

j 6 k, j odd,

8 2 WQ 21 ./,

j 6 k, j even,

(3.5)

with

A1 .v, w/ D .rv, a1 rw/ .v, div.b1 w// C .v, c1 w/ .v, .J1 .U //1 w/,

A2 .v, w/ D .rv, a2 rw/ .v, div.b2 w// C .v, c2 w/ .v, .J2 .U //2 w/,

(3.6)

and the additional adjoint data is defined recursively as

Œ1

2

D

1,

, 2Œj D .J1 .U ¹kj C1º //2 , 1Œj 1 ,

, 1Œj D .J2 .U ¹kj C1º //1 , 2Œj 1 ,

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

j 6 k, j odd,

(3.7)

j 6 k, j even,

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

839

where Jm .V / is the Jacobian of fm evaluated at V .

If we wish to highlight the final (kth) iteration, then we can write

X

.e ¹kº , / D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C

R1 U1¹kj C1º , 1Œj I U2¹kj º

26j 6k, j even

C

R2 U2¹kj C1º , 2Œj I U1¹kj º .

X

(3.8)

36j 6k, j odd

Proof

In the following, we simplify notation in the functions f ; so, for example, we write

f1 .x, u1 , u2 , Du2 / f1 .u2 /, and so on.

.e ¹kº , / D e2¹kº , 2Œ1

D A2 e2¹kº , 2Œ1

D A2 e2¹kº , 2Œ1

Œ1

D A2 u¹kº

A2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1

2 , 2

Œ1

¹kº

Œ1

D f2 u¹k1º

,

,

A

U

2

1

2

2

2

D f2 U1¹k1º , 2Œ1 A2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 C f2 u¹k1º

, 2Œ1 f2 U1¹k1º , 2Œ1

1

¹k1º ¹k1º

Œ1

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C Lf2 .u¹k1º

,

U

/e

,

1

1

1

2

R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C J2 U1¹k1º

e1¹k1º , 2Œ1

1

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C e1¹k1º , 1Œ2

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C A1 e1¹k1º , 1Œ2

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C A1 e1¹k1º , 1Œ2

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C R1 U1¹k1º , 1Œ2 I U2¹k2º

¹k2º ¹k2º

Œ2

C Lf1 .u¹k2º

,

U

/e

,

2

2

2

1

R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º CR2 U1¹k1º , 1Œ2 I U2¹k2º C J1 U2¹k2º

e2¹k2º , 1Œ2

2

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C R1 U1¹k1º , 1Œ2 I U2¹k2º C A2 e2¹k2º , 2Œ3

..

.

D

X

R2 U2¹kj C1º , 2Œj I U1¹kj º C

j 6k, j odd

X

R1 U1¹kj C1º , 1Œj I U2¹kj º .

j 6k, j even

(3.9)

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

840

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

The estimate in this case takes into account the numerical error arising from each component solution and the inherited errors passed between iterations. Following the discussion in Section 2.2.1,

we are using the adjoint naturally associated with the analytic iterative solution operator. We use

¹kº

between u¹kº

‘local’ linearization Lfi u¹kº

,

U

and Uj¹kº to define the required adjoints for

j

j

j

each component equation in the iteration. The effects of this linearization can be controlled assuming sufficient regularity of the solution and a priori convergence of the discretization, and we expect

the estimates to be accurate for all sufficiently accurate numerical solutions. The global adjoint of

the iterated solution operator is therefore obtained by a sequence of ‘single physics solves’. We note

that we still have to estimate the analytic iteration error E ¹kº .

3.1.2. Block Gauss–Seidel iteration. Next, we consider a block Gauss–Seidel operator decomposition iteration.

Theorem 3.2

The representation formula for the numerical error e ¹kº is

.e ¹kº , / D

k

X

j D1

k

X

R2 U2¹kj C1º , 2Œj I U1¹kj C1º C

R1 U1¹kj C1º , 1Œj I U2¹kj º , (3.10)

ƒ‚

… j D1 „

ƒ‚

…

„

within iteration errors

between iteration errors

where the corresponding adjoint problems are

A2 , 2Œj D ,

Œj 2

, 1Œj D ,

Œj 1

A1

,

8 2 WQ 21 ./,

,

8 2 WQ 21 ./,

j D 1, : : : , k,

D .J1 .U ¹kj C1º //2 , 1Œj 1 ,

j D 2, : : : , k,

D .J2 .U ¹kj C1º //1 , 2Œj ,

j D 1, : : : , k.

j D 1, : : : , k,

(3.11)

and the adjoint data is defined recursively as

Œ1

2

,

Œj 2

,

Œj 1

D

,

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

(3.12)

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

841

Proof

.e ¹kº , / D e2¹kº , 2Œ1

Œ1

D f2 .u¹kº

A2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1

1 /, 2

¹kº ¹kº

Œ1

,

U

/e

,

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C Lf2 .u¹kº

1

1

1

2

R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C .J2 .U1¹kº //1 e1¹kº , 2Œ1

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C e1¹kº , 1Œ1

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C f1 .U2¹k1º /, 1Œ1 A1 U1¹kº , 1Œ1

C f1 .u¹k1º

/, 1Œ1 f1 .U2¹k1º /, 1Œ1

2

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C R1 U1¹kº , 1Œ1 I U2¹k1º

¹k1º ¹k1º

Œ1

C Lf1 .u¹k1º

,

U

/e

,

2

2

2

1

¹kº

Œ1

¹kº

¹kº

Œ1

¹k1º

R2 U2 , 2 I U1

C R2 U1 , 1 I U2

C .J1 .U2¹k1º //2 e2¹k1º , 1Œ1

D R2 U2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹kº C R1 U1¹kº , 1Œ1 I U2¹k1º C A2 e2¹k1º , 2Œ2

..

.

D

k

X

k

X

R2 U2¹kj C1º , 2Œj I U1¹kj C1º C

R1 U1¹kj C1º , 1Œj I U2¹kj º .

j D1

(3.13)

j D1

In this case, in contrast with Equation (3.4), there are contributions to the error reflecting both

‘within’ and ‘between iteration’ errors.

3.1.3. Relaxed block Jacobi iteration. Both the Jacobi and Gauss–Seidel operator decomposition

iterations can be ‘relaxed’ by letting U ¹kº D ˛ UQ ¹kº C .1 ˛/U ¹k1º where denotes a quantity

computed before relaxation. The approximation is obtained via

This is often performed in practice to aid convergence of the iteration but poses more challenges

for a posteriori error analysis, and we present a partial analysis to explain how the results can be

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

842

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

extended to handle relaxation. Letting UQ ¹kº , uQ ¹kº , and eQ ¹kº represent the corresponding quantities

computed without relaxation, we have

u U ¹kº ,

D u u¹kº ,

C ˛ eQ ¹kº ,

C .1 ˛/ e ¹k1º ,

.

(3.14)

Using the notation earlier, we have

.e ¹kº , / D e2¹kº , 2Œ1

D ˛ eQ2¹kº , 2Œ1 C .1 ˛/ e2¹k1º , 2Œ1

h i

Œ1

¹k1º

Œ1

D ˛ R2 UQ 2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C f2 u¹k1º

,

f

U

,

2

1

2

1

2

C .1 ˛/ e2¹k1º , 2Œ1

h i

˛ R2 UQ 2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C J2 U1¹k1º

e1¹k1º , 2Œ1

1

¹k1º

Œ1

C .1 ˛/ e2

, 2

h i

D ˛ R2 UQ 2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C e1¹k1º , 1Œ2 C .1 ˛/ e2¹k1º , 2Œ1

h i

D ˛ R2 UQ 2¹kº , 2Œ1 I U1¹k1º C e1¹k1º , 1Œ2

h i

C ˛.1 ˛/ R2 UQ 2¹k1º , 2Œ1 I U1¹k2º C e1¹k2º , 1Œ2

.1 ˛/2 e2¹k2º , 2Œ1

..

.

D˛

k

h X

.1 ˛/i 1 R2 UQ 2¹ki C1º , 2Œ1 I U1¹ki º C e1¹ki º ,

Œ2

1

i

.

i D1

To

obtain a full a posteriori error estimate, we have to repeat this argument to estimate

e1¹ki º , 1Œ2 , i D 1, : : : , k. We refrain from doing this. Clearly, repeated application of this

analysis approach results in a great number of adjoint problems to be solved. It is to be hoped

that introducing relaxation means that relatively few number history terms need to be included for

accuracy in the estimate. As expected, the decay rate of the history terms decreases as ˛ ! 0.

4. NUMERICAL EXAMPLES FOR FULLY COUPLED SEMILINEAR ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

We present a number of examples to illustrate characteristics of the a posteriori error estimate. We

also illustrate the use of the estimates as the basis to adaptively adjust discretization parameters on

the basis of relative sizes of contributions to the error estimate.

Some of the examples are used to explore the accuracy of the a posteriori error estimate in

situations in which the operator decomposition iteration is converging well. To measure the accuracy

of the error estimate, we report on the ratio of the estimate to the true error (or an approximation

computed with a highly accurate reference solution). This type of a posteriori error estimate tends to

be robustly accurate for a wide range of spatial meshes, as has been well reported in the literature.

We observe the same robust accuracy in the estimates when the iteration is converging well. Rather

than reporting extensively on that quality, we concentrate the experiments on situations in which the

estimates do not work as well as hoped.

For adaptive error control, we employ a natural generalization of the ‘mark and refine’ strategy on

the basis of the Principle of Equidistribution [1, 5–8]. In this approach, the error estimate is replaced

by a bound obtained by replacing the signed contributions to the error estimate with their absolute values. Starting with a coarse discretization—mesh with large element size and small number

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

843

of iterations—we adjust the various discretization parameters according to the relative size of the

contributions and an estimate of the computational costs associated with changes in the parameters.

This adaptive approach is described fully in the earlier paper [1].

We make one simplification as follows. In [1], we allowed the different components to have different meshes, which requires modification of the a posteriori error analysis to account for the effect

of mesh changes on the numerical solution. As will be discussed, we use the same mesh for all components of the system to avoid introduction of the additional terms in the a posteriori error estimate.

The results from the first paper can be combined with the results in this paper in a straightforward

way.

4.1. Fully coupled linear system

The first example is a coupled system of linear equations for which we can compute an exact

solution. The coupled problem is the following: Find u1 .x, y/, u2 .x, y/ satisfying,

r .˛ru1 / C b1 ru1 D f1 .u1 , u2 /,

u2 D b2 ru1 ,

u1 D u2 D 0,

x 2 ,

x 2 ,

x 2 @,

where WD ¹.x, y/ W .x, y/ 2 Œ0, 1

Œ0, 1

º,

1

5

cos 4x C cos y

˛ D 10 C 2

13

2

>

1 8

1 1

1

sin 4x

sin y , b2 D

sin 4x

b1 13

2

2

(4.1)

>

2 sin y

f1 .u1 , u2 / D 85 2 .2 sin 4x sin y C u2 /.

This system has exact solution

u1 D sin 4x sin y

u2 D 2 .sin 8x sin y=65 C sin 4x sin 2y=20/.

We select the quantity of interest u2 .x0 /, where x0 D .0.15, 0.15/.

As mentioned, we solve for u1 and u2 on a common mesh. The Gauss–Seidel iteration proceeds

Œj until kU ¹kº U ¹k1º k1 6 105 . Quadratic finite elements are used to compute ˆŒj

1 and ˆ2

Œj Œj approximations to 1 and 2 . Starting with a uniform initial mesh, the subsequent meshes are

adapted identically using the sum of just the first four terms in the error representation formula,

namely, the sum of the following:

¹kº

1. the ‘primary’ error, "1 D R2 U2¹kº , ˆŒ1

I

U

,

2

1

¹k1º

I

U

2. the ‘transfer’ error, "2 D R1 U1¹kº , ˆŒ1

,

1

2

¹k1º

I

U

, and

3. the ‘inherited’ error, "3 D R2 U2¹k1º , ˆŒ2

2

1

¹k2º

I

U

.

4. the ‘inherited transfer’ error, "4 D R1 U1¹k1º , ˆŒ2

1

2

reg

Using an approximate delta function ıx0 , the corresponding adjoint problems used to compute

the weighted residuals are

A2 , 2Œ1 D , ıxreg0 , 8 2 S2h ./,

A1 , 1Œ2 D , div.b2 2Œ1 / , 8 2 S2h ./,

(4.2)

A2 , 2Œ2 D , div.b1 1Œ2 / , 8 2 S2h ./,

A1 , 1Œ3 D , div.b2 2Œ2 / , 8 2 S2h ./.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

844

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

Table V. The first four error terms, that is, the primary error and transfer

error at iteration k and the inherited error and inherited transfer error from

the iteration .k 1/ for example 4.1.

Primary

error ("1 )

¹kº Œ1

¹kº

R2 U2 , 2 I U1

Transfer

error ("2 ) ¹kº Œ1

¹k1º

R1 U1 , 1 I U2

0.5070 104

0.0940 104

Inherited

error ("3 )

¹k1º Œ2

¹k1º

R2 U2

, 2 I U1

Inherited

transfer error ("4 )

¹k1º Œ2

¹k2º

R1 U1

, 1 I U2

0.0010 104

0.0409 104

The initial mesh is a uniform partition with step size h D 0.1 for 200 elements. The iteration is

repeated until the total error representation estimate for the quantity of interest is less than 104 .

The adaptive algorithm ran for three iterations before meeting the tolerance. The final mesh has

2378 elements. The number of iterations used in Gauss–Seidel on the finest (last) mesh is five. The

iteration error estimate reports 1.43 106 .

The effectivity ratio (estimate/error) is 0.9976.

Table V shows the contributions to the error. We observe that the ‘transfer’ error "2 is about 1/5th

of the size of the ‘primary’ discretization error at iteration "1 , and that the ‘inherited transfer error’

"4 is 1/10th of the size of the primary discretization error. By contrast, "3 , the error inherited from

U2 at the iteration .k 1/, is 1=500th the size of "1 Figure 5 shows the first four adjoint solutions.

4.2. Effects of iteration on the accuracy of the error estimate

We next consider a fully coupled semilinear system that is solved by the Jacobi operator decomposition iteration employing continuous piecewise linear elements with initial solutions U1¹0º D x,

U2¹0º D 0. The coupled system is the following: Find u1 .x/, u2 .x/ for x 2 D Œ0, 1

such that

2

u001 D e u2 , x 2 ,

u002 D sin.ˇu1 /, x 2 ,

u1 .0/ D 0, u1 .1/ D 1, u2 .0/ D u2 .1/ D 0.

The quantity of interest is the average value of u2 over the whole domain. The sequence of adjoint

problems are

00

1Œj D 1Œj , x 2 ,

00

2Œj D 2Œj , x 2 ,

1 .0/ D 2 .0/ D 0, 1 .1/ D 2 .1/ D 0,

with

Œ1

2

D1

Œj 2

D 2 e 2 U ¹kj º

2

1Œj 1 , j odd

Œj ¹kj º

D

ˇ

cos

ˇU

2Œj 1 ,

1

1

j even.

Œj Œj Œj Quadratic finite elements are used to compute ˆŒj

1 and ˆ2 approximations to 1 and 2 , and the

6

iteration is performed until the iteration error estimator (2.11) is less than 10 or until a maximum

of 30 Gauss–Seidel iterations are performed.

We examine different sets of parameters that affect the convergence of the iteration and,

consequently, accuracy of the estimate.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

845

Figure 5. The first four adjoint solutions, that is, the primary, transfer, and the first two inherited adjoint

Œ1

Œ2

solutions for example 4.1. (a) Solution for ˆŒ1

2 ; (b) solution for ˆ1 ; (c) solution for ˆ2 ; and (d) solution

Œ2

for ˆ1 .

4.2.1. Slowly decaying history contributions. The first example demonstrates problems that can

arise when the history contributions decay very slowly. We fix ˇ D 10 and compute approximations

for D 2, 4, 8, and 16. We use a uniform mesh with h D 0.05 for the approximate solutions, and

we use a fine mesh with h D 0.005 to compute a ‘reference’ solution. We run the iterations until

kU ¹i º U ¹i 1º k 6 106 up to a maximum of 30 iterations.

The iteration converges for D 2, 4, and 8, but for D 16, the iteration cannot converge (without

relaxation) even using a finer space mesh. We report the error estimate effectivity (estimate/error)

ratios in Table VI.

These results the typical accuracy of the estimate. The estimate is even reasonably accurate in the

last case where, as noted, the iteration does not converge. This estimate in the last case is affected

by significant linearization errors because U2 does not represent u2 very well.

Figure 6 presents the partial sums of the first j history terms for the different values of . For

D 2, 4, and 8, the error contributions become relatively constant when more than five error terms

are included; but in all cases, taking simply the first error term only (the ‘primary error contribution’)

leads to a poor error estimate.

4.2.2. The effect of large numerical error on the history contributions. Let D 10, ˇ D

10, and h D 0.05. The fixed point iteration fails on a coarser mesh of h D 0.2; but for h D 0.05, the

iteration converges slowly. In this computation, the error estimate is affected both by the inaccuracies

because of linearizing about U ¹i º for i relatively small as well as the poor numerical resolution of

the adjoint solution ˆ (computed using quadratic finite elements on the mesh for U ). Both sources

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

846

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

Table VI. Effectivity ratios for example 4.2.1.

ratio

2

4

8

16

0.999942588

0.997737471

0.978260934

1.647440221

log(sum history terms)

−3.5

−4

λ=2

λ=4

λ=8

λ=16

−4.5

−5

−5.5

−6

−6.5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

# of history terms

¹kj C1º Œj ¹kj º P

Figure 6. Numerical error estimate m

, IU

including m history terms, for

j D1 R U

example 4.2.1 and D 2, 4, 8, and 16.

8

log(partial error) sums

6

4

2

0

−2

−4

−6

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

# of history terms

¹kj C1º Œj ¹kj º P

Figure 7. Numerical error estimate m

, IU

including m history terms for

j D1 R U

example 4.2.2, demonstrating that numerical error can lead to nonconvergence and poor numerical error

estimates.

of numerical error destroy the accuracy of the estimate. We see the effect in Figure 7, where we

observe that the contributions to the error estimator increase as ‘older’ history terms are included.

This is the opposite of the expected behavior that error contributions should decay and is in an indicator that the error estimator is not performing well. Large adjoint solutions relative to the size of

the solution can be an indicator of unreliable error estimates.

4.2.3. The effect of a poor initial iterate on the history contributions. Let D 10, ˇ D 10, and h D

0.05. The choice of initial data for the iteration can strongly influence the performance of the error

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

847

log(history error contribution)

4

u2{0} = x(1−x)

2

u2{0} = 0

0

−2

−4

−6

−8

0

5

10

15

History Term (j)

Figure 8. Individual ‘history’ terms R U ¹kj C1º , Œj I U ¹kj º for example 4.2.3, illustrating the

sensitivity of history error contributions to initial data.

estimator. In Figure 8, we plot the error contributions for U2¹0º D 0 versus U2¹0º D x.1 x/.

In this case, the norm of several of the early solution iterates is greater than 1014 , whereas

the norm of the converged U ¹kº is O.1/. The difficulty is that each history adjoint problem is

solved using quadratic finite elements of size h D 0.05, and the resulting use of ˆŒj instead

of Œj in the resulting error representation formula yields an error that may be bounded by

C hkU ¹kj C1º kW 1 .Œ0,1/ k Œj ˆŒj kW 1 .Œ0,1/ D C h3 kU ¹kj C1º kk Œj k (assuming smooth , ,

2

2

and u). The relative size of U ¹kj C1º and U ¹kº means that the resulting error estimate is useless,

despite the exponential decay of Œj as j increases. Incorporating additional history terms can

reduce the quality of the estimator.

4.2.4. Adaptive selection of relaxation parameter and mesh resolution. In the three previous examples, problems with accuracy of the error estimate arise from slow convergence of the iteration

and subsequent slow decay of the history contributions to the error. In Section 3.1.3, we described

an extension of the a posteriori error estimate to a version of the Jacobi iteration that employs

relaxation. The relaxation parameter directly enters into the history contributions of the error

estimate.

This suggests a generalization of an adaptive strategy in which the decay of the history contributions is monitored, and the iteration is interrupted and restarted with a new relaxation parameter

value if the history contributions are contributing too much relative to the other error contributions. The efficiency question is balancing the error contributions between those arising from the

discretization against those arising from the iteration.

Consider once again the problem in Section 4.2, with quantity of interest equal to the value of u2

at x D 0.1 (adjoint data 2Œ1 D ı0.1 ). When ˇ D 10 and D 20, this iteration cannot converge

without relaxation, regardless of mesh density.

We present the adaptive algorithm in Algorithm 4. We begin the adaptive procedure using coarse

common mesh for both U1 and U2 with h D 0.2. We perform a Jacobi iteration with no relaxation

until the convergence criterion (kU i U i 1 k1 6 107 ) is satisfied or a maximum of eight iterations is reached. At this point, the (computable) iteration error estimate (2.11) is calculated. We then

compute the error representation formula (3.4) using a variable number of history terms. In general,

the minimum number of history terms is set to be min.4, k/, but the number of history terms computed is halted if the j th history term is too small (< C1 hEt ot ) or too large .> C2 h1 Et ot /, where

C1 D 0.1 and C2 D 10. We adapt the common mesh for U1 and U2 using a standard ‘mark and

refine’ strategy applied to the a posteriori estimate using klocal errork <TOL/(# of elements) as a

marking criterion. If the iteration does not ‘converge’ or if the iteration error estimate is greater than

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

848

V. CAREY, D. ESTEP AND S. TAVENER

2

x 10−3

1

U

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

0

0.2

0.4

x

0.6

0.8

1

Figure 9. Final adapted solution for U2 for example 4.2.4 showing the spatial grid.

the numerical error estimate, then we increase the relaxation parameter ˛ and repeat the process.

Various choices for updating ˛ can be employed at this step. The process continues until both the

iteration and numerical error estimate are less than 105 .

We show the final adaptive solution for U2 in Figure 9. Generally, a quantity of interest of the

value at a point leads to a mesh that is highly refined in a local neighborhood of the point. But the

final refined mesh is nearly uniform as we see. This is a consequence of the errors inherited from

previous iterations coupled to the fact that the solutions have significantly different scales, that is,

U1 is O.1/, whereas U2 is O.10 3/). Thus, the localized contributions that should result in the

refinement of the mesh for U2 near x D 0.1 are masked by the much larger—and nearly uniformly

distributed—contributions from U1 in previous iterations.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme

MULTISCALE OPERATOR DECOMPOSITION SOLUTION OF ELLIPTIC SYSTEMS

849

5. CONCLUSIONS

We have presented an a posteriori error analysis for operator decomposition iterative solution of systems of coupled semilinear elliptic systems that use a block iterative solution technique. The analysis

provides the means to compute accurate error estimates that account for discretization errors in the

solution of each component at a given iteration, the errors passed between components at a given

iteration, numerical errors inherited from previous iterations, and errors arising due to the iterative

solution procedure. This paper specifically addresses the propagation of error between iterates in

the operator decomposition iteration solution and the effects of finite iteration on the error estimate.

We extend the adaptive discretization strategy in [1] to systematically reduce the error.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA1-09-1-0036), Department of

Energy (DE-FG02-04ER25620, DE-FG02-05ER25699, DE-FC02-07ER54909, DE-SC0001724), Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory (B573139, B584647), National Aeronautics and Space Administration

(NNG04GH63G), National Science Foundation (DMS-1065046, DMS-0107832, DMS-0715135, DGE0221595003, MSPA-CSE-0434354, ECCS-0700559), Idaho National Laboratory (00069249, 00115474),

National Institutes of Health (R01GM096192), and Sandia Corporation (PO299784).

REFERENCES

1. Carey V, Estep D, Tavener S. A posteriori analysis and adaptive error control for operator decomposition solution of

elliptic systems I: triangular systems. SIAM Journal of Numerical Analysis 2009; 47:740–761.

2. Estep D. Error estimation for multiscale operator decomposition for multiphysics problems. In Bridging the Scales

in Science and Engineering, Fish J (ed.). chap. 11, Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2010.

3. Ainsworth M, Oden J. A posteriori error estimation in finite element analysis. Computational Methods in Applied

Mathematics 1997; 142(1–2):1–88.

4. Heuveline V, Rannacher R. Duality-based adaptivity in the HP-finite element method. Journal of Numerical

Mathematics 2003; 1:95–113.

5. Giles M, Süli E. Adjoint methods for PDEs: a posteriori error analysis and postprocessing by duality. In Acta

Numerica, 2002, Acta Numerica. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002; 105–158.

6. Becker R, Rannacher R. An optimal control approach to a posteriori error estimation in finite element methods. In

Acta Numerica, 2001, Acta Numerica. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001; 1–102.

7. Eriksson K, Estep D, Hansbo P, Johnson C. Introduction to adaptive methods for differential equations. In Acta

Numerica, 1995, Acta Numerica. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995; 105–158.

8. Estep D, Larson MG, Williams RD. Estimating the error of numerical solutions of systems of reaction-diffusion

equations. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society 2000; 146(696):viii+109.

9. Larson MG, Bengzon F. Adaptive finite element approximation of multiphysics problems. Communications in

Numerical Methods in Engineering 2008; 24:505–521.

10. Marchuk G, Agoshkov V, Shuyaev V. Adjoint Equations and Perturbation Algorithms. CRC Press: New York, 1996.

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 2013; 94:826–849

DOI: 10.1002/nme