Unclassified DSTI/ICCP/TISP(99)11/FINAL OLIS : 16-May-2000

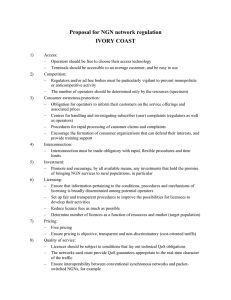

advertisement