When the University was first ... industrialists, and local trade unionists that the university was going... The University and the Community

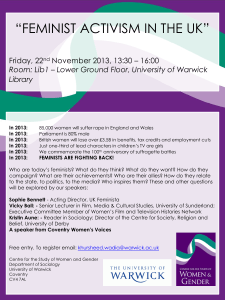

advertisement

The University and the Community When the University was first conceived it was rooted in the expectations of local industrialists, and local trade unionists that the university was going to have an impact, an economic impact, on the area. And, in the period between UCG approval being given to establish the university, and finding a Vice Chancellor, there was an intense local debate about what kind of university it should be. The industrialists wanted a technological university, but of course, the UGC wouldn’t have gone with that because already there was a downturn in numbers of people wanting to do science and it was erroneously thought that provision in the established universities was sufficient. Joan Browne, the Principal of the Coventry College of Education, stood out for having Humanities, and so there was a huge local argument. The local committee fell out big time over these disciplinary issues but one result of the argument was a strong commitment to the Humanities. However when the university actually started, the first concern was to recruit very able young academics and their concern when they arrived was to develop their courses and get their research going with the result that they had little or no contact with the community whatever, and of course when the student troubles came with its attendant local press coverage, the local population just turned away from the University; the sense of disappointment about what the university had become was absolutely acute. Relations with the City Council similarly deteriorated. By the mid 1970s when the question came up of the future of the Coventry College of Education it became clear that we had few local supporters. In the late 1960s, there’d been enormous pressure to expand the colleges of education because there was a teacher shortage, but then the birth rate went down and all of a sudden the need for new teachers subsided. So the Government decided to shrink the college education sector and to merge it with the newly created polytechnics. The question was what should happen here. Because we’d put a lot of energy into validating the B.Ed degree and had close academic relations with the College the question of its future, whether it should come into the University or not was politically important strategically. Initially we backed the College’s bid for continued independence, and when that was denied the Government said it wanted it to merge with the Lanchester Polytechnic (now the University of Coventry). We went into action to stop that, and we spoke to Shirley Williams, who was Secretary of State for Education, and got her support, but the College was actually owned by the City Council. Academics from the College and the University and administrators were organised to lobby their local city council members. I remember Jack Butterworth and I went and addressed Tory and Labour party meetings in Coventry in smoke filled rooms in party offices to try to get their support. However, the polytechnic staff voted against the merger with the College because they thought if all of the seven hundred staff moved into the polytechnic there’d be redundancies. At this moment the sudden death of the Lord Mayor switched Council control to the Tory party and there was a famous vote when the City Council conceded that the merger should be with the university subject to satisfactory terms. But all the goodwill that had been built up in the very early days of the University locally had very obviously been lost. The Idea of a University, Mead Gallery, 24-26 June 2010 One of the benefits, however, that we received from the merger was responsibility for a very large in-service teacher training function, that is, post experience training for existing local teachers. In funding terms I think it was worth 700 FTEs so it was big and this gave us, for the first time a real local community role . We followed this up by establishing a Department of Continuing Education with Professor Chris Duke, imported from Australia to be the first head. This was a new sort of department of Continuing Education for the UK where Continuing Education was viewed as a subject in its own right with the expectation that subject specialists like historians or economists might be drawn from existing departments. We created a large programme of evening classes to which many staff contributed and then moved on to start part time degrees, the two plus two degree and certificate courses, all of them under the auspices of Continuing Education which was itself based on the Westwood campus along with the in-service education programme. We also opened a downtown suite of offices in Foleshill in Coventry to conduct day and evening classes. This all did a great deal to change relations between the University and the community. Two other things happened at about the same time. The first was that Professor, now Professor Lord Bhattacharrya, arrived from Birmingham and over the next few years set up the Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) which took the University right back into the disciplinary area where local industry originally wanted us to be; the second was that we founded the Science Park, and that took us back into working with the City Council. The origin of the Park was the Chief Executive of the City Council saying to Jack Butterworth in 1980 in the teeth of the recession of the time ‘Look, this city is grinding to a halt, we've got 17.5% unemployment , what can the University do to help?’ This was a genuine appeal from the City Council and after the fight over the Coventry College we responded extremely vigorously and found them to be excellent partners. Indeed much of the credit for the initial development of the site is down to them and the Park did contribute significantly at that time to changing Coventry’s image from being simply a ‘metal bashing’ environment to being a centre for high tech development. Maintaining this kind of double strategy of being on the one hand the modern Oxbridge and on the other making significant contributions to the locality and the region both economically and culturally is difficult to pull off but perhaps more than any other UK university Warwick seems to have achieved an effective balance between the two missions. Mike Shattock Interview with Cath Lambert and Laura Evans The Idea of a University, Mead Gallery, 24-26 June 2010 The 1970s Student Troubles at Warwick MS:[The student troubles] were essentially middle class kinds of concerns about running the Students Union building rather than as in the US about Vietnam or at Berkeley changing society. If you look at the old Students Union building, before the extension was put on and the recent upgrade, it was designed as a building with a senior common room on the top floor, a middle common room for non academic staff in the middle and the students on the ground floor. The students wanted to run and occupy the whole building. Eventually after many sit ins and much dissent the senate agreed to the students’ proposal and we created a mixed staff common room in Rootes, which then fell apart because nobody actually used it. But many academics joined the argument for a single Students Union building. These were often, though by no means exclusively, academics who were fairly politically or socially radical. People took sides against, what you might call the general university management view. There were also other issues that came in about the overall management of the University. And it split the Senate, and if you read the archives, you'll see the Senate was meeting every fortnight; there were student occupations of buildings: my office was always being occupied. And it was very painful rebuilding the university after that and there were later issues over student rents, catering and so forth which inflamed student opinion all over again. When the central administration was in what's now Coventry House we had a number of organised break-ins and occupations. You try conducting a senate meeting when there are a massed women’s group out on the roof, trying to get in through a side door into a Senate meeting to protest about something. LE: Why? What was the protest about? MS I've forgotten entirely and it was something which the Senate could do nothing about but I remember having to go out on the roof, and talking to people and the Senate receiving a delegation which entered off the roof itself. These kind of occurrences were so frequent in the early to mid 70s that we had to change all the locks on the building and I actually had an alternative suite of offices in the engineering building, and we had a process, where a very large young administrative assistant had the job of organising the retreat, chaining up doors inside the Senate House as we went, and transferring key filing cabinets over to the engineering building so that the administration of the University could somehow be continued. The troubles came and went remarkably quickly and by 1975 the University was significantly a different place. Now, I think you might say that the troubles made the university a much more consensual institution than it would have been otherwise—it found that it had to find ways to talk through disagreements, and of course the most distinctive impact of the troubles was the creation of the Steering Committee. That has been the most fundamental element in the management of the university ever since. So in a way you could say that the troubles and the family, as it were, falling out, brought people together in a new kind of alliance. Mike Shattock Interview with Cath Lambert and Laura Evans The Idea of a University, Mead Gallery, 24-26 June 2010 The Idea of a University, Mead Gallery, 24-26 June 2010