T G L E

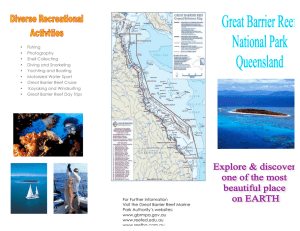

advertisement