IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST

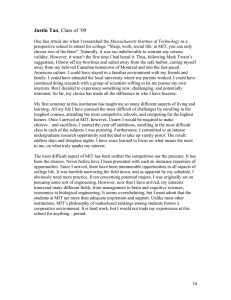

advertisement