A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FOR THE MALTESE ISLANDS

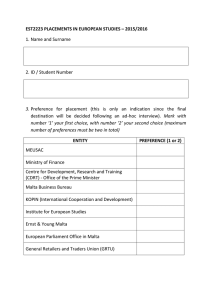

advertisement