"SLUMLORDISM" -- POSSIBLE TENANT E. V!H ITLOCK

advertisement

"SLUMLORDISM" -- POSSIBLE TENANT

~1ARY

E.

V!H ITLOCK

REr~EDIES

LAndJ.ord, landlord

l'iy c-o of h<:J s sprunG a leo k

Don't you 'member 1 told you

~·Jay lost v1eek ../

5~out

it

LGndlord. landlord

Thos e st ~ ps is .broken dbwn

~hen you come up yourself

It's a wonder you don't fall down.

Ten bucks you say 1 owe you~

'l'en bucks you say is due?

~£11, that's ten bucks more'n I'll pay . you,

Ti :J l you fix this bquse of new.

·

\~h a t?

You r,o.nna ·get 'eviction. orders?

You f::onna cut off my heat?

'·

·

You gonna take my furniture and .

Tbro"' it in the street?

U~-huhl

You talking high and mighty

Talk an---- till · you get through ·

You ain't gonna be able to say t3 word

1 f l la.nd. my fist_ on you. ·

·

Police.l Police 1

Corne and eet tbis manl

He's trying to ruin the gov.ernment

And overtake the land.

..

..

·Cooper's whistle

Patrol · b:·ll

Arr€:st

Precinct statiori

Iron cell

Headlines in ·Press:

..

:t-1AN ·. THREATENS LJJ';DLORD

. •· .

'

· TENAN'l' HELD NO ElLIL '

~udge

Gives Negro 90 Days . In .

· ; county·.Jail

·*Ballad 6i the .Landlord

.by Lanes ton Hughes · ·

I<'rom .J··i ontage of a Dream

· ·. :Deferred, ·1951

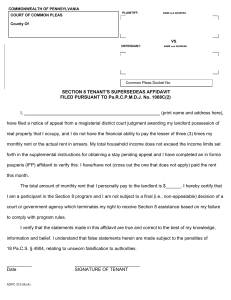

" SLUNLORDI SW' -- POSSI BLI!; TliliAN T RLJv.EDIl'-S

I.

II.

Ill.

IV.

V.

VI.

Introduction

A. Coolmon law doctrine

B. Doctrine of Caveat Emptor

Housing Conditions of Today

Responsibilities of the Parties

A. Duti e s of Landlord

1. Ka jor Repairs

2. QUiet Enjoyment

3. Implied Condition

B. Duties of Tenant

1. Paym ent of rent

2. Care of Property

Municipal Housing Codes

Possibl e Remedi es

A. Rent Strikes

b . Hent Withholding

C. Hec ei vors hip Action

D. I mpli ed \'ia rranty of Ha bili ty

b . Products Liability

1". Intentional Infliction of ~l, enta1 Anguish

G. Liability in tort

for Personal Injuries

,

Conclusion

"SLUMLORDISIvl" -- POSSIBLE Tl!:NANT RE.Xl!.Dll!.S

Before recent judicial and legislative reforms were

effected, the common law relating to landlord-tenant relationships revolved around two central principles.

First, the owner of property was under no obligation to

the tenant to make repairs.

Related to this was the doc-

trine that in the absence of an express lease provision,

the landlord was held to have made no promise that the

premises were habitable.

Secondly, the lease covenants

were deemed independent, and a substantive breach of the

lease by the landlord did not discharge the tenant from

his responsibility to pay rent.

In the vast majority

of jurisdictions these doctrines are still law.

These doctrines evidently were created by the demands of a highly agrarian, feudal society in which the

I

tenant bargained reall:y for the use of the land for

'f arming and grazing.

i'As a consequence thereof a leaseI

hold was regarded primarily as a conveyance of an interi

est in land and only ~econdarily

as a leasing of build,

ings. So the common l 'aw rules reflected the fact that

,

I

the tenant farmer usually

was in full control of the

,

I

land and buildings and had skills to make the necessary

repairs.

Today the slum dweller is unable to make repairs for

himself.

Yet these dqctrines are still applied.

Be-

-2-

caus e the law pla ced no contractual duty on the landlord to repair the tenant has no ba sis for withholding

l'

rent to make repairs. ; American Law of Property 5 3.11

i

at 203 (A.J. Casner ed • 1952).

A tenant's obli gation to

pay rent often continued even after he vacated tbe dwelling due to substandard bousing conditions.

Yet even

when the landlord expressly agreed in the l ease to make

repairs, many courts held that a tenant's obli ga tion to

pay rent was not discharged if the landlord failed to do

so.

Montgomery y. llJocher, 194 Ky. 280, 239 S.W. 46

(1922), Reaume y. Brennan, 299 Mch. 305, 300 N.W. 97

(1 941).

'rbese decisions and o t bers like them were based

on the c9ncept . tbat tbe landlord's obligation to make

repairs and the tenant's duty to pay rent are not mutually dependent.

for

Because a tenant could not deduct damages

l andlord's creach of covenant from his rental pay-

ments, bis only remedy was an independent action against

the l andlord for brea.c h of contract.

The defense of constructive evict i on has only been

applied when the premises are completely unfit for human habitation and the tenant actually has vacated the

premises.

A tenant has no right to remain on the pre-

mises and wi thbold reI'1!t i to force the l andlord to make

re pairs.

i

Therefore, this remedy has proved only mari

ginally effective and because of the severe shortage

-3of alternative housing

has provided but little relief

for the poor tenant.

Eecause at common, law the rental of real estate was

,

vi ewed as a sale of possession for the term of the lease,

2

i

the doctrine of caveati emptor applied.

Therefore the

i

landlord generally was under no duty to maintain the

premises in a habitable condition.

Slum districts grew

as America became more industrialized with migration of

people to the cities.

Standard concepts of landlord and

tenant were not appropriate in the ghetto.

in Pines V. Perission :statedl

The Court

"The need and social de-

sirability of adequate housing for people in this era

of rapid population increase is too important to be rebuffed by that obnoxious legal cliche, caveat emptor.

Permi tting landlords to rent

I~umbledown ' houses is at

least a contributing cause of such problems as urban

I

blight, juvenile delinquency, and high property taxes

for conscientious landlords." Pines V. Peri ssion, 14

Wis. 2d 590, I I I N.W.2d 409 (Wis. Sup. Ct. 1961).

According to the 'publication of the Justice in Ur-

•

ban America Series, 1970, entitled Landlord and Tenant

almost 70 million Americans are tenants.

3

Three-fifths

i

'

of the non-white population

and nearly one-ttird of the

I

white population live !in housing belonging to others.

This lack of

,I

sui~able

housing presents pressing

-4problems for Americans.

Ten percent of the total popu-

lation live in substandard housing.

The Department of

Housing and Urban Development defines substandard housing as "(I) sound but lacking in plumbing facilities,

(2) deteriorating and lacking full plumbinc , or (3)

dilapidated."

This is , a reference from The National

Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, Report at 257

no. 36 (1968).

Three out of · ten nonwhites live in subI

standard housing, one ?ut of ten whites does.

This

publication notes that: the average American family spends

15 percent of its budget on housing but emphasizes the

fact that others pay more -- from 20 to

35

percent.

Nonwhite ,tenants face the additional trauma in finding

adequate housing.

Statistics indicate that they pay

about 30 percent more rent than white famili es to Eet

the same quality of housing.

Therefore, $5,500 would

be required by an urban nonwhite family to secure housine while on the other' hand only $4,100 would be necessary to afford a white, family of the same quality of

housing.

In speaking of slum areas, reference is usu-

ally being made to Black, Chicano, or Puerto Rican racial

ghettoes.

Open housing may exist in law, but racial

,

discrimination exists in fact .'

A national housin~ shortage, substandard and over!

crowded dwellings, high rent costs, and racial dis-

-5crimina tion -- all these problems worsen the legal issues

between landlord and

t~nant

today.

Then there is the

added concern as uniformity of laws in the area of

landlord and tenant vary widely, especially as they relate to the poor.

In response to the rigidity of the common law and

th e ineffectiveness of , traditional municipal code enI

forc ement techniques,

i

~everal

states have enacted legis-

lation in the last few i years strengthening remedies directly available to tenant to force compliance with

housing standards.

There is little uniformity among

these remedies, each with emphasis on pecularities in

its own jurisdiction • . In addition to legislation a lready in force many proposals have been put forward for

discussion,

~ncIUding

Tenant Code.

the Model Residential Landlordi

This paper's

majo~

the landlord to repair :i.

thrust will be attempts to force

The various types of remedies

being considered today include repair and deduct statutes, rent strikes,

re~eivership

actions, and the im-

plied warr onty of habitability.

First, there should be consideration of some basic

princi pIes.

The rela tion of l 'a ndlord and tenant, ei";

ther express or implied,

is created by the terms of

,

which the person desighated

"tenant" eenerally enters

,

-6into possession of land under another person known as

a landlord.

The lease is an executory contract and a

present conveyance.

It creates a unity of contract and

present conveyance.

It also also concerns the term and

reversion to the owner after its termination.

A writ-

ten lease explains in detail wh e t a landlord must do.

Usually, he has the responsibility to make major repairs.

The duties of the tenant include the obligation to pay

rent.

In most jurisdictions courts hold the tenant

must pay even if the landlord fails to meet his obligation.

The law also holds that a tenant, by entering

into a contract to rent, implies a promise to take reasonable Care of the owner's property.

This is true re-

gardless of whether this is contained in the lease or

not.

If the tenant damages the apartment, beyond what

is considered "normal wear and tear" he commits waste.

,

An equally important duty of the landlord is to

provide the tenant with qUiet enjoyment of the premises.

In other words, the landlord promises to allow the tenant to live in the apartment or dwelling without disturbing him or allowing other tenantw to disturb him.

Even if the lease

does ~ not

,

state this, the law implies

,

such a promise when contracting with the tenant.

The law of a few states requires the landlord to

meet an implied condition.

By law, they must provide

-7a place "fit for the habitation of human beings."

This

duty does not depend o.n its being specifically stated

in the lease.

When the landlord offers an apartment

for rent in 'such states, by la,w he implies that it is

a fit place in which to live.

As a background to the problems of ghetto housing,

one should consider a municipal housing code.

Many

cities have housing codes or laws, imposing specific

duties on the landlord.

These set minimum standards

for buildings to insure the health and safety of the tenants.

In large citiesi, where hundreds of substandard

I

buildings exist, codes' are not regularly enforced.

,

Understa:t:fed housing agencies inspect buildings in,

frequently.

Some land',l ords claim it would be finan-

cially impossible to m'a ke all repairs necessary to

meet housing code

sta~dards.

The requirements of a

housing code are gener,a lly lower standards as contracted

to those of building c,o de standards.

Thus housing codes

have not solved America's housing problems.

Codes usually impose strict requirements on the

condition and occupancy

of residential buildings, covI

,

ering such matters as the provision of heat, venti la,

,

tion, lighting facilities, and hot water. Structural

requirements are also imposed.

bach building should

be maintained to provide

, decent living conditions for

-8its occupants.

There are various means available to enforce housing codes.

One includes criminal s anctions ceing imposed

on the landlord's failure to comply.

5

The theory of

criminal enforcement is that any l andlord threatened

with criminal prosecution will be deterred from permitting the violation to continue.

And other property own-

ers would be more apt to make necess ary repairs after

viewing a fellow landlord convicted under the code.

!

But for various r~asons, this sanction does not

produce the expected results.

Administrative devices

for delay are available such as giving the landlord a

specific period in which to make the repairs.

A land-

lord could pursue administrative appeals i f he dis a grees

with the inspector's jud gment which may involve an evidentiary hearing with subsequent appeal and oral argument to a higher body.

The city, of course, cannot

file cri minal charges until all these procedure s have

been exhausted.

Then, too, if the landlord goes ahead

and makes the needed repairs, criminal charges probably

will not be brought even though serious defects could

have been present for substantial periods of time.

Code enforcement is also dealt with by municipal

licensing, by housin g offici als who inspect the buildinr annually.

In theory,

the license is denied unless

,

i

:-9the building is in full

co~pliance

with code standards.

Yet a defaulting landlord can still maintain his prop,

erty until a hearing and final appeals have been ex6

D.C. Housing Reg. § 3102.2 (1968).

hausted.

In the final analysis even if a property owner is

ultimately convicted, repairs may never be made if the

trial court has no jurisdiction to compel repairs.

So

municipal enforcement techniques have proved incapable of

bringing substandard h9using up to code requirements

or of halting further deterioration of much inner city

housing.

Even the shift from governmental enforcement

;

to new legal remedies with direct tenant participation

has not been adequate • .

Housing code enforcement, both through government

and more recently through tenant action, has emerged as

the primary weapon in dealing with slum conditions by

limiting theirexpansipn until federal housing subsidy

programs come of age.

It was around 1900 that housing codes were first

developed.

Because of their paternalistic nature, ten-

ants were given no legal rights to directly enforce the

housing stand~rds.

The only remedy was to complain to

a local housing official, who 'i n turn could act exactly

as he wished.

About 5,000 municipal and county governi

ments have enacted housinr, codes.

I

7

National Commission

-10on Urban Problems, Blllldine the American City, at 276

(1968) •

Under certain conditions a tenant may consider his

lease to be invalid where housing code violations exist

on his premises and th~ landlord refuses to correct them.

For example, one court I has held that housing code requirements are an

impl~ed

warranty of habitability in

I

the lease, and where housing code violations occurred

during the term of the lease, the tenant had a right

to stop paying rent on the ground that the landlord

breached this implied warranty by failing to correct

the violations.

Grass y. First National Realty . Corp.,

428 F.2d 1071 (C.A.

D~C.

1970).

In order to obtain better housing conditions and in

attempts to force landlords into compliance with housing

code provisions, tenants sometimes have conducted rent

strikes.

These

involv~

a procedure under which tenants

may organize as a group and collectively agree to withhold the payment of rent until the landlord corrects the

i

condi tions about which' the tenants have complaine d.

I

I

When a group of tenants, conducting a rent s trike,

sou ght rerr,oval of a st:a te court action for the appointment of a recei vor for cOllect'i on of rents on the ground

that their civil rights were being violated, a federal

district court in New Jersey denied the removal inasmuch

-11-

as r ent strikes "Tere not sanctioned under the Civil

8

The court noted however, that the

Ri ghts Act of 1960.

New Jersey state courts, had sanctioned rent strikes.

j

Newark housing Authority y. Henry, 334 F.Supp. 490 (D.C.

N.J. 1971).

In another case in which tenants were conducting a

rent strike against a landlord and paying their rents

into a credit union fund, it was held to be error on

the part of the trial 'court when it granted injunctive

relief to the landlord prohibiting the tenants from pursuing the rent strike.1 Dorfmann y. :boozer, 414 l<'.2d

1168 (C.A. D.C.

In order to

1969)~

forc~

compliance with housing codes, a

number of states have ;enacted laws that provide for the

,

termination of the tenant's obligation to pay rent.

Al-

though not uniform in their applicability the basic purpo s e i s to deny the landlord the rental due him for the

period of time he is in violation of the code.

The first of these statutes would be rent abatement.

Under this type of statute the pr e s ence of housing code

violations on the premises constitutes an absolute defense to any action broueht

for non-payment of rent.

,

,

Therefore, the tenant is relieved of his rental obliga9

tion until the violations have been corrected.

Sinc e tenant remedies in the area of housine code

-12-

i

vtolations involve time-consuming judicial proceedings

that result in delays in making repairs, some states

~

have resorted to enacting rent receivorship laws.

10

The court under this remedy appoints a receivor for the

building when a iandlord refuses or fails to repair conditions constituting housing code violations.

Proceed-

ings to have a court so do are usually initiated by a

designated municipal

Provision is made for giv-

a~ency.

ing proper notice to mortgagees and persons holding

liens against the

prop~rty,

and the receivor then acts

to undertake the necessary repairs to bring the building into compliance with the code.

out of

r~nts

collected by him.

He recoups the costs

Such a solution has not

been very successful dUe to the red tape and bureaucratic

delays involved whenever there is a public agency involved.

The second type of statute is rent withholding.

Rent withholding in two different forms has been advanced as a possible solution to coerce slum landlords

into maintaining their! property in a habitable condi tion.

i

The first, "a rent strike," _lOuld require the tenants

!

· to pay their rent into: registry of the court or some

,i

.,

escrow account ',until landlord made the necessary repairs.

On the other hand, welfare officials could with-

hold the rent when welfare recipients live in substandard

-13-

housing.

Yet these solutions can be self-defeating if

the landlord needs the funds withheld to make necessary

repairs.

New York has eliminated this problem by or-

dering tha t the money ~e deposited with the court, who

in turn would have the repairs made.

11

Therefore the

right to withhold would occur upon one or two occurrences -- (1) tenant or municipal housing agency peti,

tions court for determination that rent withholding is

warranted or (2) the local

housing agency certifies that

,

a building is eligible for rent withholding without

judicial intervention.

12

New York and Illinois have

special statutory procedures that allow social welfare

agencies ,t o .... i thhold rent payments when a building that

hOUS ES welfare recipients is badly

de~tenanted.

13

The third type of statute ·would be those ....here the

tenant has a statutory right to repair code violations

him self and deduct the ; costs thereof from his rent.

The

California repair and deduct statute, however, limits

i

tbe use of this tenant ' remedy to once in any twelvemonth period.

14

At common law, there was no warranty of habitabil;1 ty.

In an l!.nglish case, Colljns y. liopkins, the court

found an exception to the rule by saying there was an

implied warranty that furnished houses be fit for human

habitation.

Pines y. Perission, 14 Wis. 2d 590, Ill .

-14N.W.2d 409, 412-13 (1961) has accepted this.

~uite

recently the trend has developed that the im-

plied warranty of habitability runs parallel with the

doctrine of implied warranty of merchantability.

The

New Jersey Supreme Court has taken the lead in advancement of such a theory.

The warranty in Henningsen

V. bloomfield, Inc., 32 N.J. 358, 161 A.2d 69 (1960),

says that when a manufacturer puts a new car into the

stream of trade it carries an implied warranty that it

is reasonably suitab1e ' for use.

This was extended to the

sale of real property in Schipper V. Levitt and Sons, Inc.,

44 K.J. 70, 207 A.2d 314 (1965).

nut the Schipper Co.

limited the warranty to mass produced housing.

a Texas case, Humber V.

t~rton,

However,

426S.W.2d 554 (Tex.

Sup. 1968), did not limit warranty to mass developer of

homes but did limit the warranty to the builder-vendor.

The New Jersey Court in, the case of Cintrone V. Hertz

Trllck Leasing, 450 N.J~ 434, 212 A.2d 769, 775 (1965),

said there is no good reason

for restricting such war,

ranties to sales. Thi~ was applied to new and used vehicles.

Reste Realty Corp. V. Cooper, 53 N.J.

~44,

251 A.2d

268 (1969), combined the Schipper and Cintrone doctrines

by establishing an implied warranty of habi1itability

:

against latent defects in existence when lease began.

!-15I

i

The Reste Co. establisl1ed a constructive eviction ylhich

i

is a defense to a landlord action to collect rent that

1$

is owed him.

I

If the itenant can prove that the land-

lord has failed to perform covenants in the lease, tbe

tenant can claim that he has been constructively evicted

from the property and is not liable for rent under the

lease.

But the constructive eviction remedy has no per-

manent effect as the landlord can go right ahead and

rent property to some other poor person in need of housing.

Then, too, many courts

require a reasonable time

i

i

after premises have become uninhabitable for a tenant

,

to abandon, to establish a constructive eViction and if

a tenant cannot prove tacts

necessary to establis~ con,

structive eviction, he is not only liable for rent arrearages, but still must find new housing.

A tenant

may feel he will not be able to find suitable housing

or housing at all.

The Hawaii decision, Lemle y. Breeden, 51 Hawaii

486, 462 P.2d 470 (1969), took the position that immediate abandonment is not irequired in establishing a conI

structive eviction.

T~iS opinion by Judge Levinson termed

I

the abandonment requirement as " an "absurd proposi tion,

contrary to modern urban realities."

Lemle adopted the

view that a lease is basically a contractual relationship

-16and that "legal fictions and artificial exceptions to

wooden rules of property law aside • • • in the l ease

of a dwelling house • , • there is an implied warranty

of habitability and fitness for the use intended." (at

p. 474)

As a result, "the basic contract remedies of

damages, reformation, and reversion" were available to

the tenant.

!d. at p. , 475.

Contract remedies ' are thus of much significance but

an action founded in tort could provide a more serlous

threat to a landlord.

Attempts have bEen made to apply strict liability

to defect i ve housing.

and Humber

v,

Schipp er V. Levitt and Sons, Inc.

Morton used an implied warranty to estab-

lish strict liability.

The case of Kriegler V. Mchl er

Hom es, Inc. applied the doctrine of products liability

in tort without the collateral doctrine of implied warranty.

269 Cal. App. 2d 224, 74 Cal. Hptr. 749

(I 969)

•

In Kriegler and in Schipper, mass production and sale

,

of homes was used to establish lia1:ility.

Yet this

solution's effect will not ever be that far-reaching

until courts remove the restrictions imposed by these

cases.

Products liability deals with products defective

I

I

when they left the hands of th'e manufacturer or person

who controlled them.

included.

Later defects in products are not

So if a slum tenant tried to apply strict

-17liability in tort to

d~fects

such as fallin e ceilings,

broken windows, unsafe stairs, etc., occurring subsequently,

these would not be covered.

Then, too, one of the basic principles established

by strict liability was that a consumer needed protection

from defects not reasonably discoverable by ins pection.

!

Yet many of the defects present in substandard housing

are clearly evident.

A ghetto resident must attempt to

find th e least dangerous place to live but he would be

aware of such defects.

So strict liability in tort is

really not that benefi9ial to the slum dweller.

In 1967 Sax and Hiestand, in thei~ Slumlordism as

16

a Tort, , urged that slumlordism should be a "tort,

liabili ty for intentiopal infliction of severe emotional

distress."

The rationale is that anyone who refused to

repair ' substandard housing imposes on others a horrible

and oppressive lifestyte.

Such a lifestyle creates

sever e mental and psychic

distress which injur es the

,

tenant.

Decause of the intentional element involved,

i

17

punitive da ma ges would be available.

A few jurisdictions have accepted this emotional

distresss tort but they have not made "outrage" the sole

18 '

test for liability.

The Restatement of Torts suggests

more defininite mental reactions such as fri ght, horror,

grief, shame, humiliation, embarrassment, anger, chagrin,

-18disapPointment, worry and nausea.

There would also be

problems of burden of proof, measure of damaees, causation, plus the accompanying threat of trivial cases that

mi l' ht flood the courts.

Benjamin Mazow in I his Housing Codes and a Tort of

L~w

SJIJrnlord1srn, Harvard

Review 522, 539 (1968), suggests

that a landlord should :be

liable in tort for personal

!

injuries that are the ~esult of a defect which violates

a housing code.

Public housing deals with the problems facing indie;ent tenants.

units.

Even so, · great many places still nE;ed

There is also

"projects."

~n€

stigma of living in the

Livine; in one adds to one's turd en of being

poor as it strips away disguise and pretense by identifying poverty by address.

Raising children there can

be most difficult teca~se in many instances these places

i

are headquarters for crime and its expansion.

Thus many

i

people turn to private l housing.

The law:'·of landlord-tenant: is .not ..so lacking in conceptual development

th~t

the indigent tenant must nec-

essarily be denied redress in court.

The heart of the

matter is not entirely the shortcomings of the substantive law, rather it is a combination of related problems:

the procedural

~nomaly

,

of a statute which grants

the rights but excludes otherwise acceptable defenses,

1

-19lacks provision for tenant-plaintiffs and counsel to

represent them and recalcitrant judges whose sympathies

I

,

lie with landlords upon whom the poor descend.

i

i

F00TNOTl.!:S

,

1. 1 American Law of Property, @ 3.11, at 203

(A.J. Casner ed. 1952)~

2.

W. Prosser on Torts, § 63, at 411 (3d ed 1964).

3.

Land10rdBnd Tenant, Justice in America Series,

1970.

4. J. LEvi P. Hab1utze1 L. Rosenberg and J.

Whi te, EODhL RESinhN TIAL LANDLO RD-ThlJANT caDi ('rent.

Dr a ft) 1969) (published under the auspices of the American .!Jar Foundation). ,!

5.

6.

D.C. Housing Reg.

~ 2104 (1968).

,

rd. at § 3102.2 (1960).

,

7. NATIONJ.L CO LKl SSI01i ON URbAN PHOBLl'J:;S, BUILDING TIm AMIillI CAN CI TY, ' p. 276 (1968).

~

8.

Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C.

3604.

9.

New York Nultip1e Dwelling Law, S 302-9.

10. , Wisconsin Laws 1969, Chap. 299, Jan. 9, 1970.

New Jersey L'aws 1971, Chap. 221f, June 21, 1971. .

11.

12

New York Real Propert y Action Law

(HcKinney Supp. 1969).

Pa. Stat. Ann:. Art. 35,

§

§

776 (6)

1700-1 (Supp. 1970).

13. New York Soc. \'Ielfare Law S 143-6 . (NcKinney

1966), Ill. Rev. Stat. Chap. 23, S 11-23 (Supp. 1970).

14. Cal. Civ. Cod e Sess. 1941.1) 1941.2, and 1942.1

as amended by Laws 1970, Chap. 12$0, J\'ov. 23, 1970.

15.

1965) •

W. Bus by, Real Prop erty,

16.

65 Mich. L. Rev. 869.

17.

Prosser, Torts,

~

77, at 173 (3d ed.

§

2, at 9 (3d ed. 1964).

18. Restatement (2d) of Torts

at 77 (1965).

§

46, comment j.

CAS ES

Cintrone y. Hepz T)uck Lea sing, 45 N.J. 434, 212 A.2d

.

769 , 777 1965.

Dorfma nn y. Boozer, ', 419 It' .2d 1168 (C.A.

D.C. 1969).

Gr as s y. Fi rst National Rea lty Corp., 428 F.2d 1071 (C.A.

D. C. 1970 ).

Hennjn gs f n y. E1oomfi e1d, Inc., 32 N.J. 358 , 161 A.2d

69 1960 ).

.

;

Humt er y.

~ orton,

426 S.W.2d 554 (Tex. Su p 1968).

!

Kr iee ler y. 1ich1er SOID t S, I~c., 269 Cal. App. 2d 224,

7 Cal. Rptr. 749 1969.

LeID1e y. h eeden, 51 Hawaii 486, 462 P.2d 470 (1969).

}.iontc;omery y. Dlocher, 194 Ky. 280 , 239 S. W. 461 (1922).

Newar )< Housing Auth or~tY y. Henry, 334 F. Supp. 490

(D.C. N.J. 1971 •,

Pines y. P € ri~SiOn, 14 Wis. 2d 590, 111 N.W.2d 409 , 41213 (1961 •

Re ste Rea 1JY Corp. y. tooper, 53 N.J. 444, 251 A.2d 268

( 1969 •

.

Re a ume y, I r ennan, 299 Vieh. 305, 300 N.W. 97 (1941).

SehiP~i~ {i9~~}:tt aud ' Sons, Inc., lf4 N.J. 70, 207 A.2d