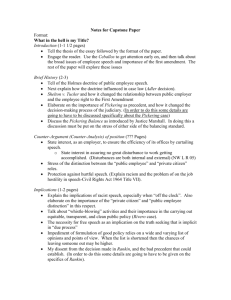

PICKERING EMPLOYEES AND FREE SPEECH II. 7

advertisement