Nebraska’s Non-Metropolitan Economy Pillars of Growth in

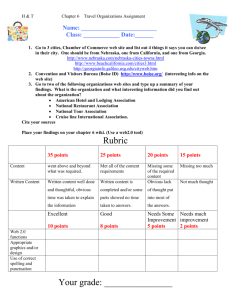

advertisement