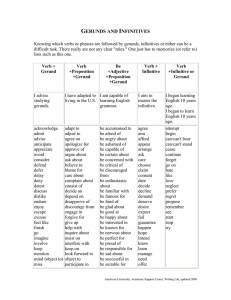

envy Matthew Reeve *

advertisement