Rules of Evidence in Disciplinary Hearings in State-Supported Universities THE CASE LAW

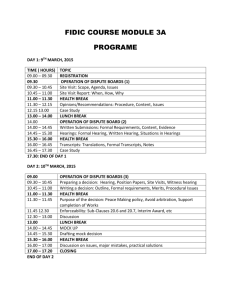

advertisement

Rules of Evidence in Disciplinary Hearings in State-Supported Universities THE CASE LAW In both state and federal courts, the modern trend in case law is away from the rigidity of the exlusionary rules of evidence. I The entire field is regarded as anachronistic,2 and of such awesome complications that the American Law Institute refused to attempt a restatement of it. 3 Those acknowledged as having the greatest expertise in the field of evidence are least satisfied with the current state of the law. Professor Charles T. McCormick stressed the need for simplification, especially in the area of the exclusionary rules;4 Professor John Wigmore called the hearsay rule needlessly obstructive,5 and then devoted 1144 pages J. "The trend of the law in recent years has been to turn away from rigid rules of incompetence, in favor of admitting testimony and allowing the trier of fact to judge the weight to be given it." On Lee v. United States, 343 U.S. 747, 757 (1952). See also Universal Camera Corp. v. NLRB, 340 U.S. 474, 497 (1951); Funk v. United States, 290 U.S. 371, 376 (1933). In a price discrimination case arising under the Clayton Act, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit said it could not understand why the attorneys for both sides were being so "formal about the admission of evidence," and that even in criminal trials, "it is better . . . to admit, than to exclude, evidence and in such proceedings as these the only conceivable interest that can suffer by admitting any evidence is the time lost, which i& seldom as much as that inevitably lost by idle bickering about irrelevancy or incompetence." Samuel H. Moss, Inc. v. FTC, 148 F.2d 378, 380 (2d Cir.), cerl. denied, 326 U.s. 734 (1945). 2. To put it another way, the law of evidence is now where the law of forms of action and common law pleading was in the early part of the nineteenth century. Furthermore the rules of evidence have become so complicated as to invite comparison with those of equity pleading . . . . Morgan, Foreword to MODEL CODE OF EVl1)ENCE at 5 (1942). The law of evidence is in such a confused and confusing condition that it is almost impossible to draft a rule which is universally accepted without qualification. [d. at 69. 3. K. DAVIS, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW TEXT § 14.02 (1959): Professor Morgan, reporter for the American Law. Institute, is quoted as saying the refusal was made "because its (the Institute's) members were convinced that no restatement could eliminate the obstructions to intelligent investigation which currently accepted doctrines have erected." 4. That part of the law of procedure known as evidence has not responded in recent decades to the need for simplification and rationalization as rapidly as other parts of procedural law. . . . Some directions in which as it seems to me improvement may be sought are the following: The relaxation or abandonment, in trials before the judge without a jury, of the exclusionary rules, apart from the rules of privilege. McCormick, Preface to J. MCCORMICK, LAW OF EVIDENCE at xi (1954). 5. The needless obstruction to investigation of truth caused by the Hearsay rule is due mainly to the inflexibility of its exceptions, to the rigidly technical construction of those exceptions by the Courts. . . and to the enforcement of the rule wh~n its contravention would do no harm, but would assist in obtaining a complete understanding of the transaction. 5 J., WIGMORE, EVIDENCE § 1427 (3d ed. 1940). HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 357 (1969-1970) [Vol. 1:357 TEXAS TECH LA W REVIEW 358 to that rule and its exceptions. The reason for the plethora of complicated evidentiary rules is traced by most commentators to a mistrust of the layman juror by the early courts,' an attitude no longer regarded as sound. The exclusionary rules especially were grounded on the notion of protecting "untrained jurors" from evidence which could possibly mislead them. 7 The Model Code of Evidence, on the other hand, adopted the view that the modern juror should be treated simply as a normal human being, perfectly capable of sifting and weighing evidence, and making rational judgments based on that evidence. 8 UNIVERSITY DISCIPLINARY HEARINGS A. The Exclusionary Rules (non-constitutional) The relaxed and liberalized attitude toward the admission of evidence once considered excludible has been most prevalent in the field of administrative law, of which university disciplinary hearings form a part. Emphasis of the liberalization has been on such venerable concepts as the hearsay rule, the opinion rule, the best evidence rule, and the rules of privilege. J. The Hearsay Rule While this best known and least understood of all the exclusionary rules has been defined with painstaking care,' the thrust of the rule is to eliminate from the courtroom any evidence the credibility of which rests on someone outside the courtroom. In those instances where the out-of-court assertion is offered without reference to the truth of the matter asserted, the hearsay rule does not apply}O For example, the testimony of witness A regarding out-of-court statements made to him by B are clearly hearsay if introduced for the purpose of proving the truth of such statements. It was felt that if the evidence could not be 6. Morgan, supra note 2, at 15. 7. K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.03 (1959). 8. Morgan, supra note 6, at 16. 9. Warning that "simplification is falsification," Professor McCormick proceeded cautiously to define the rule as follows: "Hearsay evidence is testimony in court or written evidence, of a statement made out of court, such statement being offered an assertion to show the truth of matters asserted therein, and thus resting for its value upon the credibility of the outof-court asserter." J. MCCORMICK, LAw OF EVIDENCE 460 (1954). Professor Wigmore, pointing out that "cross-i:xamination is the essential and real test required by the rule," stated that it was a "rule rejecting assertions. offered testimonial/yo which have not been in some way subjected to the test of Cross-examinations . . . ." 5 J. WIGMORE, EVIDENCE § 1362 (3d cd. 1940) (Wigmore's italics). 10. 5 J. WIGMORE, EVIDENCE, §§ 1361, 1788 (3d ed. 1940). as HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 358 (1969-1970) 1970] DISCIPLINAR Y HEARINGS 359 tested by cross-examination it could not be considered trustworthy. Thus, the numerous exceptions to the rule usually rest on the notion that the evidence sought to be admitted is trustworthy (in spite of its hearsay character), or necessary (other evidence is simply unavailable). Since the rule was originally formulated for use in jury trials to protect the layman juror from misleading evidence, and since there are no juries in administrative hearings, an application of the hearsay rule in the latter proceedings is regarded as unnecessary and entirely inappropriate. 11 Existing case law has recognized this and dismissed as without merit the contention that judicial rules of evidence be followed. The decisions suggest that hearsay is admissible in such proceedings if the administrative body is aware of the hearsay character of the evidencel ! and is otherwise in a position to "exercise a fair or intelligent judgment. "IS Therefore, the admission of hearsay into an administrative hearing is not necessarily grounds for later reversal in state or federal courts." 2. The Opinion Rule The requirement of knowledge from actual observation, rather than mere opinion, inference, or belief is one of the earliest and most pervasive of the early common law attitudes toward the testimony of a witness. It has been suggested that the rule against opinion is more inflexibly construed in this country than it was in the early English common law, even though the two judicial systems had different ideas as to the meaning of the word, "opinion."15 What the rule actually rejects is pure guesswork, or belief as opposed to personal knowledge or observation. For example, if witness A testifies that in his opinion B did not have the intelligence to appreciate the danger of going onto a street car track without looking or listening, such testimony is inadmissible where there are sufficient facts to allow a jury to reach its own conclusion. The opinion rule has never been regarded as II. K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.03. 12. "Clearly, there is no merit in the contention that plaintiffs were deprived of procedural due process because the Committee did not follow the rules of evidence usually applicable in judicial proceedings . . . . The Committee indicated an awareness that at times it was listening to hearsay evidence and weighed it as such." Goldberg v. Regents of Univ. of Cal., 248 Cal. App. 2d 867, 879,57 Cal. Rptr. 463, 475 (1967). 13. Knight v. State Bd. of Educ., 200 F. Supp. 174, 180 (M.D. Tenn. 1961). 14. The usual rule is that "admission of incompetent evidence is no reason for setting aside an order that is supported by competent evidence." K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.08. 15. J. MCCORMICK, LAw OF EVIDENCE 21 (1954). Early English judges were apparently convinced that "opinion" denoted some sort of bias or preconceived notion, while in this country the word was used "without suggesting that it is well- or ill-founded." [d. HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 359 (1969-1970) 360 TEXAS TECH LA W REVIEW [Vol. 1:357 applicable to the administrative process, and the entire emphasis in this field has been on the amount of weight to be given the witness's testimony, rather than upon the question of whether he was qualified to testify in the first place}6 3. The Best Evidence Rule Originally, this phrase had as its meaning the best proof of any given situation, necessarily relegating to a secondary position any other evidence which suggested that better proof was available. Today, this rule is specifically limited to a requirement of "the production of the original writing."17 For example, if A wrote a letter, making two identical copies, it would make no difference which one he sent, but the one sent would become the original and the other a copy. If the original is not produced or accounted for at trial, the evidence of its contents would not be admissible. This has never been a requirement of administrative hearings; indeed, while the stress in trials before juries is on oral evidence, written presentations have come to be almost universally accepted in many types of administrative adjudications. 4. The Rules ofPrivilege There is an obvious distinction between the rules of privilege and the other exClusionary rules previously discussed. The latter group has been devised by the common law courts as a means of guarding against the admission of evidence which is somehow tainted with unreliability. The privilege rules admittedly serve no such purpose-their sole aim is to "shut out the ligh,t,"18 to guard against inquiry into some relationship which, for one reason or another, society regards as sacrosanct. Familiar examples are the constitutional privilege against self-incrimination, communications between attorney and client, husband and wife, and in some jurisdictions, doctor and patient, and priest and penitent. The Administrative Procedure Act,19 by implication 16. See generally. K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.13 and cases there cited. Davis points out that the federal courts have consistently rejected the argument that an agency cannot accept the expert testimony of its own staff members. 17. J. MCCORMICK, LA~ OF EVIDENCE 409 (1954). 18. [d. 152. ' 19. 60 Stat. 237 (1946), 5 U.S.c. §§ 1001-11 (1958) at § 7(c) provides, in part: "Any oral or documentary evidence may be received, but every agency shan' as a matter of policy provide for the exclusion of irrelevant, immaterial, or unduly repetitious evidence and no sanction shan be imposed or rule or order be issued except upon consideration of the whole record . . . ." Though "shan" is always construed as mandatory, it nonetheless remains up to the board to determine what evidence is "irrelevant, immaterilil, or unduly repetitious"; ~yond this, there is the fact that privileged communications are almost never irrelevant or immaterial; on the HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 360 (1969-1970) DISCIPLINARY HEARINGS 1970] 361 at least, apparently vests in the hearing board the discretion as to whether the rules of privilege shall be observed; however, knowledgeable writers in the field have suggested that privileged evidence is probably an exception to the broad provision that any evidence may be received-especially the .constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. 20 Similarly, the other privileges should be entitled to equal recognition. 2 \ B. The Exclusionary Rules (constitutional) In addition to the common law exclusionary rules just discussed, certain constitutional safeguards have been erected for the protection of the accused. The most important of these are search and seizure (fourth amendment), confrontation and right to cross-examination (sixth amendment). J. Search and Seizure In the area of university disciplinary hearings, it is now settled law that prior to expulsion a student must be accorded notice and some opportunity for a hearing. 22 While regarding as inessential fully developed judicial proceedings, the courts have nonetheless held that the due process clause of the fourteenth amendment is applicable to students, though in a somewhat more flexible way.23 Therefore, it is obvious that the hearing board in a university disciplinary action must concern itself, to some extent at least, with constitutional safeguards. Currently significant in the specific area of search and seizure is Moore v. Student Affairs Committee of Troy State University,24 where the contrary, they may be highly relevant else they would not be considered privileged in the first place. Does this mean the board may, in its discretion, force disclosure of privileged information? 20. K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.08. 21. ld. In theory at least, none but the constitutional sanction would have to be recognized by the board, but actual practice appears to be otherwise. 22. Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Educ., 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir.), eert. denied. 368 U.S. 930 (1961). 23. "We are confident that precedent as well as a most fundamental constitutional principle support·our holding that due process requires notice and some opportunity for hearing before a student at a tax-supported college is expelled for misconduct." ld. at 158. "This is not to imply that a full-dress judicial hearing, with the right to cross-examine witnesses, is required. . . . Nevertheless, the rudiments of an adversary proceeding may be preserved without encroaching upon the interests ofthe college." ld. at 159. 24. 284 F. Supp. 725 (M.D. Ala. 1968). On February 28, 1968, a search of plaintiffs room in a campus dormitory revealed possession of marijuana in violation of state law. No search warrant was obtained. In a relatively closed hearing at the University on March 27, 1968, plaintiff was indefinitely suspended. He brought an action for reinstatement. The case was dismissed by the fifth circuit court, which held that a state university regulation that "the college reserves the right to enter rooms for inspection purposes" was facially reasonable as necessary to the institution's duty to operate the school as an educational institution. HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 361 (1969-1970) 362 TEXAS TECH LA W REVIEW [Vol. 1:357 plaintiff challenged the constitutionality of a university regulation. a The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that the constitutional distinction between the right of the school authorities to search and the right of the dormitory student to privacy must be based on a reasonable belief of the college authorities that a student is using a dormitory room for a purpose which is either illegal or which would substantially interfere with campus discipline. Because expulsion from a university is an administrative proceeding and not a criminal action, this standard of "reasonable cause to believe" is lower than the criminal law standard of "probable cause." The rationale given for the distinction is the special relationship of the student and college and the necessity that the college continue to function as an educational institution. The court reasoned that since there are no criminal penalties involved, due process and such administrative proceedings as expulsions do not require a full-blown adversary hearing which would be subject to the rules of evidence and all constitutional criminal guaranties. 2I The Moore court reasoned that the search here involved would not be a violation of the fourth amendment, although that amendment is not by its terms limited to criminal proceedings. Z7 The court regarded as settled law the concept that the fourth amendment does not prohibit reasonable searches when the search is conducted by a superior charged with the responsibility of maintaining order and discipline. Z8 However, such precedents may be of limited value insofar as they are based on military law and governmental employment regulations. Relying on Dickey v. A/abama State Board of Education Zl and Burnside v. 25. Plaintiff asked the court for: (I) Readmission because of a denial of due process. (2) A declaratory judgment that evidence seized in his room was not admissible in any criminal proceeding against him. The cour.t held that that was clearly unavailable. See 28 U.s.C. § 2283 and Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U.S. 117, 120 (1951), where the Court said, "We hold that the federal courts should refuse to intervene in State criminal proceedings to suppress the use of evidence even when claimed to have been secured by unlawful search and seizure." (3) A determination that the evidence seized in his room violated his fourth amendment right prohibiting illegal searches and seizures. 26.. Moore v. Student Affairs Comm. of Troy State Univ., 284 F. Supp. 725, 730 (M.D. Ala. 1968). 27. The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath of affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. U.S. CONST. amend. IV. 28. United States v. Grisby, 335 F.2d 652 (4th Cir. 1964); United States v. Collins, 349 F.2d 836 (2d Cir. 1965); United States v. Donato, 269 F. Supp. 921 (E.D. Pa. 1967), affd. 379 F.2d 288 (3d Cir. 1967); United States v. Miller, 261 F. Supp. 442 (D. Del. 1966). 29. 273 F. Supp. 613 (M.D. Ala. 1967). HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 362 (1969-1970) 1970] DISCIPLINARY HEARINGS 363 Byars. 30 the Moore court concluded that constitutional rights will be protected as long as such rights do not substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the university. Rules to effect this end are presumed facially reasonable, despite the fact that they may infringe somewhat on the prohibitions of the fourth amendment. 31 Thus the balance struck is weighted heavily in favor of university rules that are considered reasonable and necessary. While the Moore court based its holding largely on the fact that "mere expulsion" is not a criminal proceeding, it would appear that this distinction is of doubtful validity. The fourth amendment is not in its terms limited to the criminal process, while others clearly are, Frank v. Maryland,32 in which a 5-4 decision upheld a city ordinance requiring householders to admit warrantless housing inspectors, was overruled by See v. Seattle33 and Camara v. Municipal Court. 34 The Camara court struck down a portion of San Francisco's Housing Code35 on the basis that the underlying purpose of the fourth amendment is to safeguard the privacy of individuals against arbitrary invasions by governmental officials, and took pains to point up the anomaly of a doctrine which provided that a person and his property are "fully protected by the Fourth Amendment only when the individual is suspected of criminal behavior."38 While holding that warrants were required, the Camara court evolved a new species of "area probable cause" which is substantially less than the probable cause needed to justify a criminal search warrant. 37 The result then, is apparently a sliding scale drifting downward from "probable cause,"38 through "area probable cause" to "reasonable cause to believe." Whatever else such a scale may mean, it is at least obvious that neither the framers of the Constitution nor the present Court envisaged the safeguards of the fourth amendment as applicable solely to criminal proceedings. 30. 363 F.2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966). 31. People v. Overton, 20 N. Y.2d 360, 229 N.E.2d 596, 283 N.Y.S.2d 22 (1%7). 32. 359 U.S. 360 (1959). 33. 387 U.S. 541 (1967) (regarding commercial enterprises). 34. 387 U.S. 523 (1967) (regarding private residences). 35. San Francisco Housing Code § 503: RIGHT TO ENTER BUILDING. Authorized employees of the City departments or City agencies, so far as may be necessary for the performance of their duties, shall, upon presentation of proper credentials, have the right to enter, at reasonable times, any building, structure, or premises in the City to perform any duty imposed upon them by the Municipal Code. (Compare the university regulation, supra note 23.) 36. Camara v. Municipal Court, 387 U.S. 523, 530 (1967). 37. Id. at 534-39. 38. For a definition of probable cause, see Dumbra v. United States, 268 U.S. 435, 441 (1925). HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 363 (1969-1970) 364 TEXAS TECH LA W REVIEW [Vol. 1:357 In the field of administrative law, the fourth amendment guaranty against seizure of papers and effects has not been viewed as a restriction on records and reports brought before the hearing body.39 But whether evidence unlawfully seized is admissible in a university disciplinary hearing is somewhat more problematical; if the Moore holding is correct with regard to federal courts, it would seem that under the less stringent evidentiary rules requirements of administrative hearings, such evidence is clearly admissible. But the impact of Camara and See, if any, upon student expulsion proceedings has yet to be decided; until this is done, the safer course for administrators would appear to be to admit only evidence which has been properly obtained by a warrant. 2. Confrontation and Cross-examination It is fairly evident from the trend of the case law that the right to cross-examination is not required in a university disciplinary hearing. 40 In Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education,41 the leading case in the area, the basic requirement is simply one of fundamental fairness in a hearing which preserves the rudiments of an adversary proceeding. Dixon does not require confrontation and cross-examination. Such a full-blown hearing, the court reasons, with all the attendant publicity, could tend to disrupt the educational process. The Administrative Procedure Act allows cross-examination to the extent that it is required for a full disclosure of the facts,42 but it is apparent that the discretion of whether to allow it rests with the hearing board. Only a clear abuse of that discretion would require reversal in a judicial appeal. In summary, the trend of both case law and administrative law is to replace the exclusionary rules of evidence with discretion, and base findings on the kind of evidence on which responsible people would ordinarily rely. The residuu m rule-a requirement that an administrative finding be based on evidence which would be admissible in a jury trial-will not necessarily require a court to set aside the 39. K. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 3.05. 40. Madera v. Board of Educ., 386 F.2d 778, 786 (2d Cir. 1967), cert. denied. 390 U.S. 1028 (1968); Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Educ., 294 F.2d 150, 159 (5th Cir.), cert. denied. 368 U.S. 930 (1961); Jones v. State Bd. of Educ., 279 F. Supp. 190, 197 (M.D. Tenn. 1968), af/d. 407 F.2d 834 (1969); Due v. Florida Agricultural & Mechanical Univ., 233 F. Supp. 396, 402 (N.D. Fla. 1963). 41. 294 F.2d ISO (5th Cir.), cerr. denied. 368 U.S. 930 (1961). 42. 60 Stat. 237 (1946), 5 U.S.c. §§ 1001-11. Section 7(c) provides, in part: "Every party shall have the right to present his case or defense by oral or documentary' evidence, to submit rebuttal evidence, and to conduct such cross-examination as may be required for a full and true disclosure of the facts." HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 364 (1969-1970) 1970] DISCIPLINAR Y HEARINGS 365 findings of the hearing; it may do so or not, depending on the individual facts of each case. At any rate, the residuum rule is generally rejected by the federal courts, and most state courts merely note its existence and decide the case on whether it believes the evidence to be of genuine probative value. There is a basic dissatisfaction with the exclusionary rules in both courts and administrative agencies, and one may expect their eventual demise. 43 Richard Maxwell 43. ~. DAVIS, supra note 3, at § 14.17. HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 365 (1969-1970) HeinOnline -- 1 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 366 (1969-1970)