.. The Myth of Carlsbad, New ... Disposal of Nuclear Wastes

advertisement

.

The Myth of Carlsbad, New Mexico and the Safe

Disposal of Nuclear Wastes

T. B. Nicholas, Jr .

•

"I cannot accept your canon that we are to

judge Pope and King unlike other men, with

a favorable presumption that they did no

wrong. If there is any presumption it is

the other way, against the holders of power,

increasing as the power increases."

•

Lord Acton: Letter to Bishop

Mandell Creighton, April 5,

1887. Historical Essay and

Studies, 1907.

In June 1981 the United States Department of Energy

will begin development of the nation's first Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), near Carlsbad, New Mexico, in which

military-generated and commercial nuclear wastes will be

stored in deep salt bed geologic repositories. 1

Joe McGough,

director of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, states that the

site will provide "a research and development facility to

demonstrate the safe disposal of radioactive waste resulting

from the defense activities and programs of the United States."

Although the facility was planned initially for the disposal

of

milita~y

transuranic wastes only, this New Mexico facility

will now provide for:

(1) the permanent disposal of defense(2) experimental studies conducted

generated transuranic waste;

with high-level wastes; and (3) possibly up to 1,000 commercial

spent fuel assemblies.

Under current plans, all of these

various types of wastes would be stored in a retrievable manner

until it is determined that they may be allowed to remain

safely in WIPP in perpetuity.

3

'

To date, Carlsbad residents have not formed organized

opposition to the site.

4

Though environmental groups claim

that the WIPP is dangerous and that the facility would have

negative effects on the nearby town of 25,000, Carlsbad

residents, at least elected officials, apparently are delighted

with the pr.oject.

5

"We have eight city councilmen and a mayor,

•

two state representatives and a state senator, all of whom

have been work1ng on this since 1971, and we continue to be

-

1 -

0030~1

2

elected," says Carlsbad mayor Walter Gerrells.

"Now there's

a very vocal minority that opposes it, but I think you'll find

that even the motel owners around here support it." 6

Berry

Casebolt, managing editor of the Carlsbad Current-Argus, says

"the project already brought approximately $800,000 into the

town through contracts, and now it's mushrooming.

But the big

thing I believe is that Uncle Sam is supposed to pay for new

roads, a new transportation network to bypass major cities

when they transport the stuff.

It'll really give us a boost." 7

But measured against this commercial zeal of Carlsbad and

the nuclear industry is the fact that radioactive wastes are

among the most toxic substances known to man.

The release of

radioactive wastes into the environment could cause immediate

death, cancer, or genetic mutations in catastrophic proportions.

And because some of these wastes remain dangerous for tens,

and even hundreds, of thousands of years (depending on the

·particular waste product), they must be isolated from the biosphere for unprecedented periods of time to avoid harmful exposure to humans.

In order to mediate these competing interests of sc1ence

and society, the need for stringent regulation of these hazardous waste products by an independent agency with technical

expertise has been recognized by Congress.

The Nuclear Regula-

tory Commission (NRC), the federal agency with primary regulatory responsibility over radioactive wastes generated by cornmer-

-

2 -

00303

cial nuclear operations, was created for this specific purpose. 8

The regulatory SGheme was established and developed by the

Atomic Energy Act of 1954 (AEA), as amended by the Energy

Reorganization Act of 1974(ERA) 9 and the National Environmental

Policy Act of 1969.

10

Despite the recognized need for stringent

control, however, serious flaws pervade the substance and form

of the federal system for the management and disposal of radioactive waste.

These deficiencies are due in part to the

magnanimity of the waste products and their unknown effects,

the deficiencies of past regulatory attempts, and the now complete inability of state governments to intervene for the

adequate protection of public health and safety from the

potential hazards of the nuclear industry.

This article will first discuss the wastes--their toxicity

and magnitude--which are critically important in understanding

the potential threat of the WIPP experiment in Carlsbad.

I

will then focus on the problems of radioactive waste, past and

existing, and the inadequacies and flaws in the •federal

versus state' dichotomy of nuclear waste management and disposal.

Finally, I will point to other federal attempts at establishing

a permanent disposal site, and the continuing uncertainty

surrounding the Carlsbad project.

It is of critical importance that the people of West Texas

and Southeastern New Mexico understand the true dimensions of

•

the problem; in the meantime, we cannot afford to be trapped by

the commercial zeal of the nuclear industry into a short-order

solution that explodes on the next generat1on.

Q030G

I. The Wastes

The major categories of radioactive wastes involved in

the Carlsbad experiment include those from the processing

and use of radioactive materials:

"tailings" from uranium

mills, "high-level" wastes from nuclear power plants, and

transuranic and low-level wastes, consisting of contaminated

work materials.

a. Uranium Mill Tailings

The first step in producing enriched uranium fuel for

nuclear power plants is the milling of the uranium ore. 11

The ore, which. is usually from a nearby mine, is crushed,

ground, and chemically treated in a mill to extract and

concentrate the uranium.

The processed ore is then discharged

into a tailings pond as a solids-laden liquid.

The water seeps

into the ground or evaporates, eventually leaving a dry pile

of sandlike waste.

Uranium tailings contain natural radio-

nucleides that are highly toxic, and long lived.

For example,

thorium-230, which is a highly toxic isotope contained in large

amounts

with~n

mill tailings, has a half-life, or decay period,

of 80,000 years, and, therefore, it must be isolated from man

on the order of a million years or longer.

Human exposure to uranium mill tailings may be by the

inhalation bf wind-blown particles from unstabilized piles,

of radon gas which emanates from the piles, or of decay products

from escaped radon. 12

A person may also be exposed by direct

.

.

f

.

.

.

rad1at1on

rom the piles, or by dr1nk1ng

contam1nated

water. 13

Approximately 25 million tons of radioactive mill

tailings have already accumulated at twenty-two inactive

mill sites in eight western states. 14 Abandoned by the

operators, these piles of radioactive waste are largely

unstabilized.

But while these pose grave dangers enough,

the corning decades will pose even greater problems.

Annual

amounts of mined uranium to fuel nuclear plants are projected

to increase more than ten-fold by the year 2000. 15

Presently,

there are twenty-one mills in active operation throughout the

u.s.,

and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission estimates that

109 mills will be needed by the year 2000 to support the

commercial nuclear power industry. 16

Accordingly, the volume

of accumulated mill tailings will increase by thirty-fold

in that period.

b. Reactor Generated Wastes

Once the uranium is mined and fabricated into fuel, it

is used in nuclear power plants.

A nuclear plant generates

'

electricity by fissioning, or splitting,

uranium and plutonium

atoms in the nuclear reactor core.

electric generators.

This in turn powers

As the fissioning isotopes in the fuel

are depleted, the resulting waste product, the 'spent fuel

rods' are then withdrawn from the nuclear reactor cores.

17

Until 1977, the federal government and the nuclear power

industry had planned on chemically treating, or 'reprocessing',

•

these spent fuel rods in order to remove the unused, still

stable, material for further uee in the processing of fresh

- 5 -

00303

fuel.

When this reprocessing occurs, "high-level radioactive

wastes" are produced.

18

But in 1977 former President Carter

announced tha·t reprocessing would be deferred indefinitely,

because of possible additional risks in the theft and fabrication of nuclear explosive devices by terrorist groups. 19

c. Transuranic and Low-Level Wastes

These wastes are by-products of the nuclear fuel cycle,

and are comprised of materials such as clothing, glass, and

metal that become contaminated with radioactivity.

Transur-

anic wastes are produced primarily at reprocessing plants and

facilities where plutonium is processed into fresh fuel.

Low-level wastes, on the other hand, are produced at nuclear

reactor sites themselves, and do not include the "heavier"

radionucleides with atomic numbers higher than simple uranium,

as do the transuranic wastes.

But like the uranium mill tailings, both wastes are

highly toxic.

For example, one radionucleide produced at the

nuclear reactor stage 1n connection with low-level wastes is

plutonium-239.

It is so toxic that as little as three micro-

.

.

1 s. 20

grams--a ' spec k' --can cause 1 ung cancer 1n

an1ma

Further,

because of its exceedingly long decay period of 24,000 years,

the large quantities of plutonium produced in reactors will

remain at least potentially harmful to man for at least several

hundred thousand years .

21

•

Each of the toxic substances above will be present at the

carlsbad WIPP proJect either permanently or on an experimental

basis.

As an initial operation, it will be responsible for

0030~

housing wastes from the seventy nuclear power reactors which

22

.

- an d t h e over 500 reactors which are projecte d

a 1rea d y ex~st,

to exist by the year 2000. 23 Over 600,000 gallons of

commercial liquid high-level wastes and about 4,000 metric

tons of commercial waste in spent fuel rods already exist. 24

Measured by long-lived radioactivity, this inventory is

expected to double within three to four years, and will be

twenty times greater by the end of the century. 25

II. Problems

a. Problem 1:

Unsatisfactory Safety Record

Checkered with missteps, negligence and overzeal, the

history of waste management and disposal in the United States

has been far from satisfactory.

For example, in 1952 through 1966, mill tailings were

psed extensively as construction fill in houses, schools,

businesses, sidewalks and highways in Grand Junction, Colorado.26

The danger was only realized in 1972, when a remedial

program was instituted to remove the hazard from 700 locations. 27

The remedial program was put on an entirely voluntary basis,

and few local contractors have been interested in performing

the work. 28 No regulatory action was ever undertaken by the

federal government to prevent this noncompliance or to compel

•

any effective cleanun.

Other instances of gross mismanagement include contamination of public water supplies.

As early as 1958, it was

discovered that the drinking water in two towns below Durango,

003)0

Colorado--Aztec and Farmington, New Mexico--contained concentrations of radioactivity exceeding federal standards. 29

Radioactive concentrations in the river flora and fauna were

100 to 10,000 times the concentrations found in the river

30

water itself.

Grasses and alfalfa irrigated with the

water and consumed by livestock contained radiation 100

.

.

t 1mes

grea t er th an th e r1ver

water. 31

In the Grants Mineral Belt of New Mexico, the The

Environmental Protection Agency in 1974 found that the problem

continued to exist.

Water discharges from uranium mining and

processing in the Belt were found to contain certain poisonous

32

chemicals 7,300 percent in excess of EPA standards.

Contamination of the drinking water near the sites were found

to grossly exceed drinking water standards and to pose a

health hazard to the employees and their families. 33

Perhaps most pertinent to the Carlsbad project in terms

of similarity is the case of West Valley, New York, where

all commercial high-level wastes are currently stored.

Plans

for the project initially contemplated that all liquid wastes

could be stored indefinitely in near-surface storage tanks.

But the project was without foresight; though envisioning

repeated transfers of the wastes as old storage tanks deteriorated, no plan ever existed that ensured a safe transfer.

Even worse, to date no safe method of removing and transfering

wastes

has~been

developed, and additional special research

34

must now be conducted.

The cost of remedying the West Valley situation has been

estimated at 600 million dollars, and implementation of any

06~-:

---~

effective cleanup operation could take another fourteen

35

years.

And finally, among the still unresolved questions

is who will finance and implement the clean-up operation-the site operator, the state of New York, or the federal

government. 36

Serious safety flaws, then, have pervaded the history

of radioactive waste management and disposal.

But in these

cases previously considered, one may argue that the dangers

incurred in those instances were problems arising from the

interim storage dillemma.

When a permanent waste repository

was found, one would argue, these problems of ina~rlquate

temporary disposal would be alleviated.

This leads to the second area of possible problems for

Carlsbad:

assuming no negligence or mismanagement , as was

present in the cases above, will the site of Carlsbad be

safe?

The proposed answer in Carlsbad--storage of waste in

bedded salt deposits--must be examined in order to give any

credence to the federal government's assurance that a safe

disposal site will be developed in Carlsbad.

b. Problem 2:

The

Propo~ed

Solution

Shortly after passage of the Atomic Energy Act in 1954,

the Atomic Energy Commission and its advisors focused on

bedded salt deposits as the most likely underground geologic

formation eor the disposal of the long-lived nuclear wastes .

37

•

But a 1978 Department of Energy report now questions the

government's almost exclusive focus upon bedded salt deposits

and recommends that a variety of other geologic media be

- 9 -

003~~

considered more seiously before any permanent disposal site

is begun.

The dichotomy highlights important unresolved

scientific and technical problems which exist in spite of

Carlsbad's acquiescence to the site location.

In the most recent past, the favorite engineering solution of the nuclear industry to the problem of storage has

been the transformation of wastes from their granular state

to a glass state, then storage in bedded salt deposits. 38

But the U.S. Geological Survey, the Office of Science and

Technology Policy of the White House, the Department of

Energy's Sandia national laboratory, independent scientists from

a wide range of institutions, and Swedish researchers have

all found fallacies in the glassified waste in bedded salt

deposits approach.

The following exerpt from an environmentalist group

newsletter examines, in question and answer form, some of

the considerations which should be examined before construetion of the first permanent disposal site begins.

In short,

it examines the mode in which Carlsbad will dispose of nuclear

wastes and some possible ramifications:

Q: The nuclear industry says the waste disposal problem isn't

so serious. It says we can convert nuclear wastes into a

glass and store the glassified wastes in a salt mine. What's

wrong with this?

•

A: The problem with that solution is that it has been utterly

discredited by just about every scientific group that has

looked at it in the past two or tpree years. The U.S. Geological Survey, industry scientists in Sweden, independent teams

1475'74

at Penn State, and two laboratories of the Pepartment of Energy

have found fatal flaws in glass and in salt. Minute amounts

of water have.be~n foun~ betwe~n crystals in bedded salt

deposits. This water migrates toward a heat source, like a

radioactive waste canister. When the water reaches the

canister, it will be hot (300-400 degrees centigrade) and

salty, and recent tests show it capable of corroding almost

anything. The strongest glass tested has been obsidian. It

lasted one day. According to David Stewart, chief of the

experimental geochemistry and mineralogy branch of the U.S.

Geological Survey, 'the mystique has built up that salt is

dry and it's okay. Salt is not dry and it's not okay.'

Q: After 20 years of research on waste disposal and 30 years

of waste generation, why do we discover this now? It's

unbelievable that these things weren't known earlier.

A: That's right. But according to a prominent Stanford

geochemist, William Luth, the only exhaustive tests on glass

were done ten years ago at room temperature with distilled

water! In May 1978, a group of scientists at Pennsylvania

State University published a short report in Nature, the

British scientific journal, that fell like a bomb on the

nuclear industry. The group te~ted borosilicate glass at the

temperatures (300-400 degrees centigrade) expected in a

sealed repository. It broke into little pieces in less

than two weeks. Twelve percent of the cesium leached out

into the water and 'millimeter-size radiating yellow needles

were growing on the specimen and throughout the capsule.'

Tests in Sweden and at the Department of Energy's Battelle

Northwest Labs confirmed that strontium and cesium--the two

most dangerous short-lived waste products--leach into solution

in less than a week at high water temperatures. These tests

were with fresh water; with salt water, the tests were

catastrophic. As Dr. Stewart of the USGS has noted, 'the

- 11 -

003~~

only waste forms stable in dense brines are the noble metals

like gold and the high titanium minerals.' Nuclear wastes

are neither of these.

Q: It's still astounding that we've spent two decades thinking

about putting glassified wastes in salt mines and no one ever

tested what hot salt water would do to the glass. What reason

was used to select salt?

A: There were at least two good reasons for picking salt as a

disposal medium. It is 'plastic' or 'self-healing' when

heated and it dissolves in water. The latter doesn't sound

like a good reason, but the argument goes that if salt's

been there a million years, water hasn't. Hence, put waste

in it. The second argument has been seriously eroded--so to

speak--by the discovery and analysis of minute water migration

toward heat sources in salt. You have to remember that U.S.

waste policy has been a.paper exercise. A federally appointed

panel of eminent earth scientists chaired by Siever of Harvard

and Giletti of Brown University, reported recently, 'We are

surprised and dismayed to discover how few relevant data are

available on most of the candidate rock types even thirty

years after wastes began to accumulate from weapons development.

We are only now just learning about the problem of water in

salt beds and the need for careful measurement of water in

salt domes.' The first argument in favor of salt was its

plasticity or ability to heal cracks. But even here, salt's

advantage has been washed away. Instead of plugging holes or

cracks, such as those made during the original mine excavation,

heated salt is likely to expand, flow upward around the canisters,

leaving the containers to plummet, in the words of the Stanford

geochemist.Luth, 'like lead into water.'

•

Q: What's wrong with having the waste go further into the earth?

- 12 -

003~3

A: The problem is deep-plowing underground rivers. One

well-known aquifer ;:lies beneath the Waste Isolation Pilot

39

. New Mex1co,

.

·

a propose d d.1sposa1 s1te.

Pl ant 1n

The article, continuing, graphically illustrates the

Carlsbad project:

where its unanswered questions exist and

possible dangers lie:

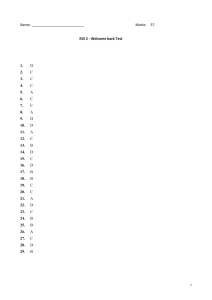

rrnnm

•- - -

AOUIFF.R

- 13 -

40

One fact which has changed significantly since the

August 1980 publication of this article is that Carlsbad,

New Mexico is-no longer a proposed site; the project was

given a go-ahead in late January 1981, and construction

will begin in June, as I have mentioned earlier.

Don Hancock of the Southwest Research and Information

Center has recognized the danger of the WIPP plan: "There

are a couple of areas within the boundaries of the site

where the seismic measurements show anomalous activity.

They can't tell what's there, but it's not what it should

b e. u41 Hancock said some of his colleagues believe that

salt beds, thought to have formed and stabilized about 30

million years ago, are in an active deep dissolution process

caused by underground water. 42

It should be pointed out that any miscalculations on

the formation's stability could be disastrous even if involving only low-level wastes.

The Carlsbad site will also

include an area for research on high-level wastes.

Joe

McGough, WIPP director who announced the construd.tion goahead, said that though the Carlsbad program had not been

entirely defined, it will definitely include about 40

canisters of high-level nuclear waste.

He said the program

is designed to find out the effect of high-level waste, largely

43

plutonium, on salt beds.

In ot4er words, the Carlsbad program is designed to rebut,

•

by experimentation, the conclusions which at least one section

of the scientific community has drawn--that the effect of

. - 14 -

003:.7

nuclear wastes on salt beds is both highly speculative and

potentially very hazardous to the biosphere with which it comes

in contact.

But let us assume for the sake of argument that Carlsbad

realizes its role as merely an experimental nuclear dump and

no longer has the zeal for the project that it currently

expresses.

What then?

Will it be able to revoke its commit-

ment to house the permanent site?

This problem has very

recently posed perhaps the greatest possible threat--the

inability of a municipality, or even state to regulate against

federal imposition of nuclear facilities.

This federal

preemption would be a disability which would prevent the

locality's preservation of the safety and welfare of its

citizens.

c. Problem 3: State Inability to Protect Its Interests

In 1971, at the outset of development of the Carlsbad

project, a New Mexico congressional delegation sought the

power to veto the WIPP project should public outcry become

43

too strong.

The effort failed, signalling the federal

preemptory notion that the nation's interests should come

first. 44 Since, the delegation has succeeded in attaching an

amendment to the plant's authorization allowing the state

consultation rights with the Department of Energy. 45 But

these

cons~ltation

rights, advisory in nature, have no affirm-

•

ative role in the state's duty to protect its citizens.

- 15 -

003~8

Therefore, the 1971 preemptive federal decision to disallow

state veto power on the

WIPP project's direction would also

disallow any state legislation-designed to protect the

public health, safety and welfare with respect to the storage

and disposal of nuclear waste.

To illustrate the 1971 decision's ominous precedence,

one may examine the case law arising during the same year.

The scope of federal preemption in the nuclear field was

defined by the principal decision in the area, Northern States

Power Co. v. State of Minnesota. 46 Northern States invalidated

Minnesota's attempt to impose radioactive emission standards

that were more stringent than the federal standards on the

basis that the state's standards were preempted by federal law.

In a recent article by Donald J. Moran, 47 however, he

discusses at length the direction in which this precedent of

federal preemption has expanded.

A recent federal district

court decision in California, Pacific Legal Foundation v.

State Energy Resources Conservation and Development Cornmission,

has held that there is a complete preclusion on states from

regulating on the subject of nuclear waste disposal.

In doing

so, it has expanded federal preemption to prohibit any state

legislation designed to protect its citizens with respect to

the storage and disposal of nuclear waste.

The California federal court had, in part, considered a

49

section of:the California Public Resources Code

which

provided that no nuclear power plant could be certified in the

state of California unless the California State Energy

- ~~003_!}

48

Resources Conservation and Development Commission (1) found

that the 'authorized United States Agency' had approved a

technology for the disposal of. high-level nuclear wastes and

(2) reported its findings to the state legislature, which had

the power to disaffirm them. 50

The court held the section of the Code unconstitutional,

enunciating two grounds for its decision.

First, the court

found that Congress had impliedly preempted any state legislation on the subject of nuclear waste disposal when it

passed the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 and its amendments in

51

1959.

Second, the court perceived the statute to be "an

obstacle to the purposes and objectives of Congress as stated

in the Atomic Energy Act." 52

States like New Mexico, when confronted with this expanding power of federal preemption in nuclear waste regulation,

are unable to properly evaluate their responsibility to promote

the public health, safety and welfare, and thus are frustrated

·in their attempts to prevent overzealous development of the

nuclear industry and its regulation.

Conclusion

There should be growing concern in the United States,

and especially in Carlsbad, New Mexico, about how to safely

and effectively

manage increasing quantities of radioactive

.

•

wastes being generated.

As I have attempted to show in my

discussion, the dangers are great, risks are high, and a

state may be continually disabled in any attempt to exercise

its power to prevent federal encroachment into its environment.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has admitted that

until 1970, whatever waste management policy that had existed

had been more. or-less ad hoc. 5 3

Repeated efforts from 1970

until January 1981 reflected failure by the government to

establish a permanent repository for two fundamental reasons-uncertainties in scientific projections and hesitance at public

outcry.

In the late 1960's, the government selected a site to

locate its first WIPP project--an abandoned salt mine near

Lyons, Kansas.

However, later investigation disclosed, among

other things, that water from adjacent mining operations might

seep into the repository and dissolve the salt containing the

waste.

In early 1972, the Lyons, Kansas, site was abandoned. 54

Then, in 1972, the Atomic Energy Commission announced

plans to build another facility to store nuclear wastes

for an indeterminable period of time, while the long search for

an acceptable, safe geologic site continued.

But in 1975

congressional appropriations were withdrawn, focusing more

pressure than ever before to find a stable geologic site.

The 1972 plan, however, has been retained as a backup system in

55

case "other repository plans failed."

With the renewed interest in the development of a deep

geologic repository, efforts were increased to locate a

suitable site.

~

In 1976, a salt formation in the state of Michigan

was promoted for investigation.

However, in June 1977, after

residents of northern Michigan had voted overwhelmingly to

prohibit the siting of a waste repository within their area, the

federal government, though under no obligation to do so,

abandoned its efforts to locate the first WIPP there. 56

A recent report of a Department of Energy task force

on radioactive waste management 57 clarifies how much uncertainty still surrounds the government's efforts to establish

the Carlsbad WIPP project site.

First, the task force notes

that the "federal gove_rnment, as an entity, has not formally

reached a conclusion on ultimate disposal of high-level

58

wastes."

Second, the report's conclusion that the federal

government's previous target deadline of 1985 for the permanent repository will now be delayed until 1988 "at the earliest

date" signals the prospect of the Carlsbad site's prematurity.

Third, the report questions the government's focus on bedded

salt deposits as the most stable medium.

It points out that

fundamental questions continue to exist about which geologic

medium is most appropriate for nuclear waste disposal, and

recommends that a variety of other geologic media be considered

more seriously. 59 And fourth, the report realizes that several

'

important technical issues remain unresolved, and calls for

further efforts in "developing scientific data, safety analysis

and systems models to improve the scientific bases for specific

60

media choice, site selection and repository designs."

The experiences with radioactive waste management in the

past have not inspired public confidence that the wastes are or

..

will be pr6perly processed, stored, or disposed of in the government's first permanent disposal site in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

- 19 -

003~

Important unresolved scientific and technical problems concerning

waste disposal remain, and the only way to ensure against the

possibility of any disaster is ·to compete with the current

commercial zeal of Carlsbad and the nuclear industry.

Without

opposition, we as a race may well be trapped by the industry

into a short-order solution which will, indeed, explode on

the next generation.

- 20 -

FOOTNOTES

1. Associated Press, "Nuclear Waste Dump Okayed Near Carlsbad,"

The Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, January 24, 1981, at A-8.

-

2. Id.

3. 43 Fed. Reg. 30,331 (1978).

4. E. Davis, "Carlsbad Nuclear Opposition Fades," The Lubbock

Avalanche-Journal, February 1, 1981, at A-1, A-16.

5. Id. at A-16.

6. Id.

7. Id.

8. The NRC was given licensing responsibility over nuclear

activities, including licensing of nuclear reactors, 42

U.S.C. §5843 (1976), and waste disposal facilities, 42 U.

S.C. §5842 (1976). Pursuant to section 301 of the Department of Energy Organization Act, 42 U.S.C. §7151 (Supp.

1977), NRC's nuclear waste management development and

research functions were transferred to the Department of

Energy (DOE).

9. 42 u.s.c. §§2011-2296 (1976); 42 u.s.c. §§5801-5891 (1976).

10. 42 u.s.c. §§4321-4361 (1976).

11. H. Linker, "Radioactive Waste: Gaps in the Regulatory

System," Denver,,Law Jour .1 (1979).

The followTng expTanation is attributable to the portion

of the article discussing uranium mill tailings, high-level

and low-level wastes.

12. Pohl, Health Effects of Radon-222 From Uranium Mining,

7 Search 345, 346-48 (1976).

13. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Summary Report: Phase I

-Study of Inactive Uranium Mine Sites and Tailing Piles,

==

9-10 (October 1974).

"

14. U.S. Ge.neral Accounting Office, Uranium Hill Tailings

-Cleanuo: Federal Leadership At Last? 1 (June 20, 1978)

[hereinafter GAO Mill Report].

--

- i

-

15. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Nuclear Power Growth 19742000, Wash 1139 at 29 (February 1974).

16. GAO Mill Report, supra note 14, at 1.

17. H. Linker, supra note 11, at 5.

18. 12 C.F.R. §50 App. F (1978).

19. Executive Office of the President, Energy Policy and Planning,

--The National Energy Plan 70 (April 29, 1977).

20. Bair and Thompson, Plutonium: Biomedical Research, 183 Science

715, 720 (1974).

21. Id.

22. U.S. Department of Energy, Nuclear Generating Units In the

United States as of June 30, 1978 (August 9, 1978).

23. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Final Generic Environ==

mental Statement on the Use of Recycled Plutonium in Mixed

== ------ ---== == -- ~===

Oxide Fuel in Light Water Cooled Reactors, NUREG-0002,

Executive Summary, at S-12 (August 1976).

24. U.S. Department of Energy, Report of Task ~orce for Review

of Nuclear Waste Management, DOE/ER-ooo4/D 66 (February

1978).

25. Id.

26. GAO Mill Report, supra note 14, at 21.

-27. Id.

28. Id. at 22-25.

29. Union of Concerned Scientists, The Nuclear Fuel Cycle 47 (1975).

-

-

30. Id.

31. Id.

32. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Water Quality Impacts

-of Uranium Mining and Milling Activities in the Grants

----Mineral Belt, New Mexico, No. 6/9/75/002 58 (September 1975).

33. Id. at 60

34. House Crimm. on Government ~erations, West Valley and the

=-Nuclear Dilemma, H.R. Rep. No. 755, 95th Cong. 1st Sess.

16 (1977).

- ii -

35. Id.

36. Id.

37. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory ~ission, Environmental Survey

-of the Reprocessing and Waste Manag;ment Portions of the

LWR Fuel Cycle - A Task Force Report, NUREG-0116, ( Supp.

==.

=

1 to WASH-1248)at D-2 (October 1976).

38. J. Harding, "The Nuclear Blowdown: The Devilish Problem of

Radioactive Waste," Friends of the Earth Foundation Newsletter (August 1980) at 14.

39. Id.

40. Id. at 15.

41. Associated Press, supra note 1, at A-8.

42. Id.

43. Id.

- 44 . I d . at A-1 .

45. Id.

46. 447 F.2d 1143 (8th Cir. 1971), aff'd mem., Minnesota v.

Northern States Power Co., 405 U.S. 1035 (1972)

47. D. J. Moran, "Regulating the Disposal of Nuclear Waste",

Vol. 85, No. 5, Case and Comment (Sept.-Oct. 1980), at 20.

48. 12 Env. Rep. (BNA) 1899, 1906 (S.D.Ca1. 1979).

49. Cal. Pub. Res. Code §25524.2 (1977).

50.

51.

52.

53.

Moran, supra note 47, at 20.

Id. at 22, 25.

Id. at 22.

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Environmental Survey

-of the Reprocessing and Waste Management Portions of the

---LWR Fuel C-;-rcle- A Task Force Report, supra note 37, at D-3.

--- --

- -

.JI

54. Id.

55. Id. at D-4.

56. U.S. General Accounting Office, Report to the Congress, The

-U~ited States Nuclear Energy Dilemma: Disposing of Hazardous Radioactive \vastes Safely 15 (September 9, 1977).

-

- iii -

57.

58.

59.

60.

Supra,

-Id. at

Id. at

Id. at

note 37.

7.

9' 52.3, 9, 26.

.

-

•

- iv 0~('..,

~

0 ti.