Dr Maria Attard

advertisement

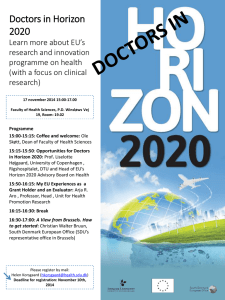

Ceremony 1 Academic Oration Monday 18 November 2013 at 1630hrs JESUITS’ CHURCH – VALLETTA Dr Maria Attard A.L.C.M., B.A. (Hons)(Melit.), M.A. (Melit.), Ph.D. (Lond.), F.R.G.S. Faculty of Arts Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development I first take the opportunity to welcome you to this year’s Graduation Ceremonies, of which this is the first, and also to thank Senate for the invitation and opportunity to address you today. At this point in time the research community is heavily engaged in discussions about the new framework programme which is set to channel all the EU’s research and innovation money for the coming seven years. Horizon 2020, as it is being called…. (and here I quote) is the financial instrument implementing the Innovation Union, a Europe 2020 flagship initiative aimed at securing Europe's global competitiveness. Running from 2014 to 2020 with a budget of just over €70 billion, the EU’s new programme for research and innovation is part of the drive to create new growth and jobs in Europe (1). I wanted to start my address highlighting this as the University of Malta has the potential and opportunity within Horizon 2020 to continue developing this important role the University has in society, particularly in the areas related to the country’s social and environmental challenges. We need more research in what Aurelio Peccei (1981) referred to the future that can still become what we reasonably and realistically want (2). Now, I am a Human Geographer by training, one that specialized in urban and transport geography and started my academic career setting up the Geographic Information Systems Laboratory at the University. The Laboratory fell under the Faculty of Science however it provided training on GIS to almost all faculties. Later I formally joined the Geography Department (an Arts subject area) and subsequently took on the role of Director of the new interdisciplinary Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development. This academic background is what has enriched my understanding of society and the world but also in the way we, as academics, have the potential to contribute. My research revolves around land transport, a nagging problem for almost everyone in society, but one which is so complex in terms of the technologies, the infrastructures, the impacts on the environment, society and the economy, and last but not least the political dimension of transport which has an impact on every aspect of Society (with a capital S). Research in this area is multi and inter-disciplinary and has been identified by the European Union as one of the Grand Challenges facing our society and that will have significant funding for research in Horizon 2020. Having said that, the importance of Social Sciences and Humanities research has been a topic of discussion in a number of venues particularly in the run up to the Horizon 2020 launch, set for 2014. At one of these events held in Vilnius in September this year, social scientists from all around Europe came together under the Presidency of the Lithuanian Government to discuss the role and benefits of Social Sciences and Humanities research for Europe. Kirsten Drotner, Chair of the Scientific Committee for the Humanities in Science Europe said that…. the complex societal challenges that we are facing today cannot be explained by physical, environmental and biological causes alone; humans play a central role. Understanding the human factor is fundamental and can only be achieved by investigating the historical, cultural and communication processes in which human life is embedded (3). My intentional focus on Social Sciences and Humanities stems from discussions which I have been involved in over the last few years, with the majority questioning the relevance of Social Sciences and Humanities in society. On one hand the question of why we should be conducting research into the human condition and on the other, more utilitarian view, what kind of contribution can social scientists give to today’s society, especially when this is continually driven by a need for an application (technological fix to some problem) and potential commercialization of research for direct economic gain? I can give you a number of examples where Social Science research is fundamental. At the conference in Vilnius I was asked to make a statement about the role of Social Sciences in Horizon 2020, particularly in relation to the challenge identified in Europe 2020 as Smart, Green and Integrated Transport. I mentioned the need to re-focus some of the effort and investment into Social science research as they (the social scientists) reflect mostly on the problems that our cities face. For example, a lot of money is spent in Europe on developing cleaner cars. Has research looked beyond the driver satisfaction and experience of an electric car versus a conventional car, in an attempt to understand more holistically the socio-economic impact of electric mobility? Stuck in traffic in a conventional car or in an electric car will certainly not improve one’s quality of life! Yes, of course, many argue that air quality will improve, but certainly not all the other impacts associated with car dependence, such as increasing travel time due to congestion, limited space for parking infrastructures at origin and destination, fatalities and injuries from road accidents, increasing cost of infrastructure maintenance, increasing obesity and poor health associated with increased car use and lack of exercise, and so on. We see our cities and urban areas growing, and not necessarily horizontally in terms of sprawl. They are certainly growing older (demographically) and changing the dynamics of land use, activities, movements, behaviour and needs. There is a growing realization that no one specific profession can resolve such complexities. Social Sciences in themselves are interdisciplinary. However that is not enough. Interdisciplinary research crossing the physical and social sciences is necessary in many cases to model and forecast spatial patterns that influence land use decisions, and subsequently help in resolving difficult decision making. My view on this is that if such interdisciplinary research had to occur, engineering and technological developments would not be so short-lived. The talk about sustainability is clearly very close to my heart. I have seen, through specific fields such as transport and urban development, the development of sustainability discourse moving from environmental awareness, to economic needs and more recently to societal aspects which, if applied intelligently, can lead to innovation. Communities have the potential to become sustainable and drive change which will support the Grand Challenges for Europe in 2020 but also beyond. The EU’s Grand Challenges focus on Health, Demographic Change and Well-Being; Food Security, Sustainable Agriculture, and Forestry, Marine and Maritime and Inland Water Research and the Bioeconomy; Secure, Clean and Efficient Energy; Smart, Green and Integrated Transport; Climate Action, Resource Efficiency and Raw Materials; Inclusive, Innovative, Secure and Reflective Societies. All are cross-cutting themes that have the potential of creating opportunities for Europe, but more importantly for European communities to come together and adopt a bottom up approach to sustainability. Andrea Colantonio (2009) defined social sustainability as the means by which individuals, communities and societies live with each other and set out to achieve the objectives of development models, which they have chosen for themselves taking also into account the physical boundaries of their places and planet earth as a whole (4) (5). I would like to expand briefly on two aspects within this definition. First is the choice that communities have, through the democratic process, to develop or adopt ways in which they lead their lives individually or as a community. The freedom that communities in democratic countries enjoy is also a responsibility. Being aware and understanding the impact of our everyday choices is fundamental to ensure safe, inclusive and sustainable environments. Second, is the reference to the physical boundaries of place. Economic development and higher standards of living have somehow diminished our perception of what in the past were boundaries set by limitations in technology. We talk of the death of distance: there is no place in the world which we cannot reach. We talk about unlimited supply of energy and resources: especially when we think of infrastructures and activities that are continuously dependent on energy (i.e. they cannot be switched off). I refer to what Stewart Udall (1980) said: All evidence suggests that we have consistently exaggerated the contributions of technological genius and underestimated the contributions of natural resources… We need… something we lost in our haste to remake the world: a sense of limits, an awareness of the importance of earth’s resources (2). A number of events have significantly impacted my understanding of these two aspects. On the larger geographic scale, the repercussions of Iceland’s volcanic eruptions on the air transport sector in 2010 were beyond anyone’s expectations. It took the sector by surprise and the preparedness by the activities which are directly and indirectly affected by air travel was non-existent. So in our choices, how do we deal with uncertainty? The uncertainty brought about by physical boundaries or limitations from the environment, whether due to climate change or as in this case a volcanic eruption, is hardly ever considered in policy as well as in every day life. The possibility of individual or community action impacting on our environment is hardly factored in. On a smaller geographic scale we look at our own community. How do our actions contribute to a better quality of life? I give here a few simple examples from my research interests in travel behaviour. In deciding about travel one would traditionally weight the cost of the journey against its purpose and distance. Many studies have now shown that in car dependent societies, this rational thinking is not done. We have the highest share of household income going to transport (in some households instead of food) and our modal choice is the most expensive one, irrespective of purpose or distance. This has a considerable impact on communities that have to share limited space resources, for example the space for pedestrians and community building, as the fear of the road keeps children, parents, old people indoors. The impact of transport emissions on health and the environment are unprecedented. Margaret Thatcher would adopt what became known as the TINA (There Is No Alternative) approach to the destruction of environmental resources to accommodate private mobility, simply because she believed people could not be persuaded to moderate their car use (6). In the past we looked differently at consumption and very differently at what community is all about. Some good practice still exists, but research shows that with progress comes undesirable impacts such as anonymous neighbourhoods, social exclusion and communities that are not really communities. Social sustainability might be just looking at the past to better understand our (sustainable) future. But it is not only about that. Social Innovation is the latest buzzword to be voiced by European politicians and on the ground, brought about by the financial crisis, the increasing unemployment and pressing social needs. It is also an opportunity for communities but also for researchers in Social Sciences and Humanities, Media, ICT and so on, to innovate and be enterprising. Many examples already exist throughout Europe, and I am pretty sure that good examples exist locally as well. As I stand here in front of you all, I wonder how many of you graduates today have spent time throughout your studies to think! Think of ways how you can contribute, how you can change what you have learnt into something creative, innovative. And this is where the potential lies, especially for students and researchers in Social Sciences and Humanities. The technological barriers which existed a decade or two decades ago for social scientists to meddle with media for example, do not exist anymore. Ask any young person today and given a few hours he or she would be able to create a website, contribute information through the use of smart phone apps, lead revolutions through social media! I refer here to the work of Richard Florida, who in 2000 wrote about the rise of a new class, the Creative Class as he called it. He defined the core of the Creative Class to include people in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music and entertainment whose economic function is to create new ideas, new technology and new creative content (7). Basically the members of this new class share a common ethos that values creativity, individuality, difference and merit. Another discovery he made was that in the age of globalization and ICT, geography is anything but dead. Place matters and companies in the services sector are attracted to locations that harbour talented, highly skilled and creative people. I strongly believe that social sustainability and social innovation will be the next big thing. For this to happen there must be a realization by society overall that the role of Social Sciences and Humanities research and more importantly interdisciplinary research has value, a value which can be exchanged into creativity, innovation and growth. May you all today, graduates of this University find the opportunity to fulfill your ambitions, be daring and creative, and through your critical thinking and actions, contribute to the sustainable development of this nation of ours. Thank you. References (1) European Commission (2013) Research and Innovation: Horizon 2020. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/research/horizon2020/index_en.cfm?pg=h2020 (2) Meadows, D. et al. (2004) Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. Earthscan. (3) Science Europe (2013) Humanities in the Societal Challenges. 12 Compelling Cases for Policymakers. Available at http://www.scienceeurope.org/uploads/Public%20documents%20and%20speeches/SCs% 20public%20docs/SE_broch_HUM_fin_web_LR.pdf (4) Colantonio, A. (2009) Social sustainability: Linking Research to Policy and Practice. Sustainable Development – A Challenge for European Research, 26-28 May, Brussels. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/research/sd/conference/2009/presentations/7/andrea_colantonio__social_sustainability.ppt (5) Colantonio, A. (2011) Social sustainability: exploring the linkages between research, policy and practice. In: Jaeger, C.C., Tabara, J.D. and Jaeger, J. (eds.) Transformative science approaches for sustainability. European research on sustainable development. Springer (6) Mees, P. (2000) A Very Public Solution. Transport in the Dispersed City. Melbourne University Press. (7) Florida, R. (2012) The rise of the Creative Class Revisited (10th Anniversary Edition). Basic Books.