J methods & tools Playacting and Focus Troupes: Theater techniques for creating

advertisement

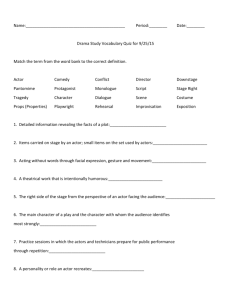

STEVE SATO AND TONY SALVADOR methods & tools Don Bishop ©1997 Artville, LLC Playacting and Focus Troupes: Theater techniques for creating quick, intense, immersive, and engaging focus group sessions J Jeff Hawkins, the inventor of the PalmPilot, was said to have carried a small block of wood around in his shirt pocket as a prototype of the personal digital assistant his company was developing [6]. As various everyday situations arose, he would take out the block of wood and imagine how he would use the device. Hawkins was acting out the use of a new product within his everyday situations. His experiential context of use helped to frame and focus Hawkins’s wants and needs, which in turn informed the design of the PalmPilot. interactions...september + october 1999 35 Creating a Shared Context Steve Sato Doblin Group steve.sato@doblin.com Tony Salvador Intel Corporation tony.salvador@intel.com 36 Focus groups that are used to develop or evaluate new products strive to achieve some of the same goals as does working with mockups. Generally, researchers are responsible for characterizing the product (the block of wood) and for creating a shared context of use (the everyday events Hawkins experienced) to focus the participant’s wants, needs, and perceptions. Providing a shared context is relatively easy if the product is an improvement on an existing object, for example, a clothes washer, since subjects have some previous understanding about how they use clothes washers. The researcher’s challenge comes when a new product with no precursor is introduced. A brand-new product is often tangible and its form has a powerful presence, in contrast to scenarios of use, which are much more abstract and ephemeral. If focus group sessions for brand-new products are not designed with these points in mind, a shared understanding of the context for use can be overshadowed by the product itself. Hawkins’s own use of the block of wood in the moment was a theatrical technique of acting out use of the product in a fully contextualized scenario. We doubt whether a more traditional focus group would have achieved what Hawkins did on his own in this case. In fact, the purpose of this work was to elicit Hawkins-like responses from typical end-users— people with no shared context of the new product concept. For new product development, the value of early, contextual feedback from real end-users about a wide variety of product concepts before they are developed is undeniable. Some previous work exists on combining theater techniques and groups of end-users in new product development [1, 4, 5, 10], but we have found no comprehensive source on such work. We have found some good sources [2, 9] that could be used to interbreed theater methods with enduser groups for new product development. With this work we hope to expand the practice in this area to include end-users efficiently, effectively, and early in product development. Focus Troupe: Where Products are Props We have observed that science-fiction movies are particularly good at highlighting the function of or interaction with a new technology over details about its form; the new product is a prop in a larger story. When new or unusual technologies are presented in science-fiction movies, often the audience accepts and understands their function, even when the details of the device are not understood; the movie provides a context that makes the device coherent. This observation led to experimenting with theater techniques in focus group sessions. We present in this section an overview of the focus troupe process [7], with an eye toward practical issues. A focus troupe session takes about 2 hours. It looks like any other focus group; an audience of about 20 people sits around tables of four or five people. However, rather than conducting a product presentation, a moderator sets the context for the dramatic vignette that will follow. Next, the first dramatic vignette is presented, featuring the new product concept or concepts. The vignette casts a familiar scenario demonstrating how the new product concept might be used. The familiar scenarios are derived from experience or, in our case, from the ethnographic work that supports the product concept. The audience then takes part in several structured conversations about the concept, armed with a full understanding of the implications, operations, and expectations of the product. To structure the conversation, we have used Edward DeBono’s “six hat” concept, which breaks a conversation into parts according to the type of comment [3]. For example, “green hat” comments are positive comments about the product. The focus troupes conducted to date have typically begun with a 6- to 10-minute opening skit that demonstrates the concepts. Following a conversation for information interactions...september + october 1999 (white hat) is a positive monologue in which an actor extols the virtue of the product concept in another context. The monologue is followed by conversations of possibility (green hat). Finally, an actor presents a negative monologue in another context, which is followed by conversations of criticism (black hat). Typically, the green and black hat conversations take place at each table and one of the actors or developers sits at that table to record the comments and answer questions. DeBono’s red hat (emotions and feelings), yellow hat (positive constructive thinking), and blue hat (controls the process) were not used. Several characteristics of the focus troupe differ from those of a focus group. The first, and most obvious, is the presence of live performers. Although having live performers ensures that no two sessions will be identical, we feel that the use of video would be insufficient because ✱ Live performers “in the round” cast a spell over the room; there is a heightened awareness—even tension—in the room. All eyes are fixed on the actors. ✱ Live performers occupy a larger part of the visual field of each audience member. ✱ Making a compelling video requires using video appropriately, an option that is neither quick nor inexpensive for most people. ✱ Live actors offer the possibility of using the techniques identified in the next section to promote an engaging and interactive experience. The second practical characteristic of developing a focus troupe versus developing a focus group is scheduling the participants and having actors available. However, one might be surprised by how many actors are around. One colleague in Boston thought of using local college drama students; they are available and would appreciate the work. Because we used no special props and no special technologies and wrote a script based only on ethnographic experiences, creating the event requires finding participants. Because a focus troupe is meant to be used early in the development process, it should be relatively low cost and easy to do. The third practical characteristic is that product designers are present during a focus troupe session. They answer questions from the audience more effectively (better) and more efficiently (with less effort on the client’s part) than the moderator, who is mostly unable to provide the best answers and who would otherwise require a lot of time and preparation to fully understand the product. Moreover, designers can answer questions in ways that facilitate the session rather than fostering an unrelated conversation about, for instance, technical details. The result of these sessions is a wide ranging set of comments and conversations about the product in the context both of the presented drama and of these people’s own lives. Analysis requires an exercise in judgment, weighing the comments and conversations against what the developers know to be true. For example, a participant who comments “this would be a great product because it works like a TV” must be weighed against the fact that the technology will not permit “it” to “work like a TV” for many years. However, by providing the drama, the audience members have a point of contrast to their lives, which appears to make their evaluative task all the easier. In effect, the comments they have are often comments about the opportunities for the product to fit into their daily lives or why the product simply is not for them. In short, we like to characterize the difference between a focus troupe and a focus group as the difference between being at the Broadway musical and listening to someone tell you about it. For the participants, the exercise is about having an experience and incorporating, comparing, contrasting that experience with their own experiences. interactions...september + october 1999 METHODS & TOOLS COLUMN EDITORS Michael Muller Lotus Development Corp. 55 Cambridge Parkway Cambridge, MA 02142 USA +1-617-693-4235 fax: +1-617-693-1407 mullerm@acm.org Finn Kensing Computer Science Roskilde University P.O. Box 260 DK-4000 Roskilde Denmark +45-4675-7781-2548 fax: +45-4674-3072 kensing@dat.ruc.dk 37 Workshop on Playacting and Focus Groups Yet, for as useful and encouraging as these early data are to us, we longed for greater interactivity with the audience. Perhaps like a good show, the drama leaves the audience wanting more at the end. However, in this case, the author is not responsible for the story, but rather the audience members themselves become the authors. We are not creating fiction; we are creating a potential experience. We feel that the audience can be enticed to participate if we provide the techniques to foster their further involvement. Our desire to create deeper contexts more quickly and greater interactivity with the audience was the impetus for hosting a workshop on combining theater techniques and group sessions at the Participatory Design Conference in Seattle, Washington, on November 13, 1998 [8]. The goal of the workshop was to generate a collection of techniques that participants can use in an evening with end-users for new product development. The techniques involve performing quick, intense, immersive, and engaging activities focused on developing a shared context of use against which end-user evaluations will make sense. The workshop produced a framework that makes two useful distinctions. First, is a concept developed to the point that sessions can be used to evaluate the product? If so, the session is evaluative. Alternatively, if the product concept is rough or is not realized, the session is exploratory, so the purpose is to generate insights and ideas for a new product. Second, who will be acting? Will actors be used, perhaps directed by the participants, or will the participants themselves be acting? For example, using these distinctions, the focus troupe approach described earlier was an evaluative session that used professional actors. When a product concept exists and actors 38 are used, the physical presence of the actors can create an intense and engaging performance, particularly if the technique chosen is free from a script and relies on the audience’s participation. When the audience participates, they begin to experience the new product firsthand, and they become more invested in the co-created situation. Furthermore, improvisation exercises are designed to create a safe space into which the participants can expand, and in the process they become invested in the actions at hand. We believe that this investment can generate quite an authentic response. Finally, we believe that when a group of potential users is gathered to explore new product concepts through using theater methods, much can be learned from how the participants co-create the new product and the context for its use. Involving the Participants In our estimation, the Participatory Design Conference workshop was successful in generating a set of theater techniques that could be used with groups for new product development. Table 1 summarizes theater techniques suggested at the workshop and in subsequent group discussions. The table includes methods that participants had either used or been exposed to, including ideas for new but unproven approaches. No distinctions between the proven and unproven techniques are made, since it was difficult to judge the extent of development and effectiveness of each technique without holding more extended discussions with each participant. The table therefore is provided as a starting point for readers in developing their own approaches. From our experiences, readers are urged to prototype the approach they choose, to realize the more subtle issues that arise in actually applying the technique in practice. For example, the way participants are instructed to play the transform game will affect what each actor chooses to show. An “X” indicates a situation in which we believe the techniques would be most effective. Some of the descriptions are self-explanatory; for clarity, we briefly describe in the following paragraphs the theater techniques interactions...september + october 1999 shown in Table 1. We have also included comments from our own experiences on the potential benefit of using various techniques. ✖ Have actors play roles. Either an actor or the audience plays out a role as it exists, or as they would imagine it would require, given the introduction of a new product. This technique appears to be useful whether or not the audience participates and for both evaluating and generating new product concepts. ✖ Act out scripts. Actors are best suited for methods involving scripted acts; who scripts the acts is important. Here the participants’ processes of developing the script and directing the actors provide further insights for the researcher. Additionally, someone with domain expertise should review the scripts to glean further insights. ✖ Freeze and change what happens next. A participant watching a scene unfold can call out “freeze” and intervene either in person or by directing the actors’ actions. We have found that the facilitator will need to remind participants of their goal, so that the exercise stays focused. ✖ Have audience act out skits. The audience produces and performs their own scenes. Here the processes of developing a skit provides further insights for the researcher. Because of the open nature of this technique, researchers will have an opportunity to understand how the participants collaboratively structure their ideas and experiences. ✖ Debate and adopt a position. Debating gets participants invested. Switching positions helps participants Actors used, Audience acts, Actors used, Audience acts, product product no product no product concept exists concept exists concept concept Theater technique Play roles through, e.g., job interviews or sales training X Act out scripted x Have audience call “freeze” and change what happens next x Have audience act out skits X X X X X X Debate and take one position and perhaps switch positions later x Use same script but change the attitude or emotion x Have same person play all the roles X X X X X X X X X Act out everyday situation, add a constraint (e.g., water costs a lot) x X X X Act out everyday situation, provide fairy-tale props x X X X Act out everyday situation, have a magic wand x X X X Act out what goes on inside a product X X Imagine an actor or a simple object as the product X X Change situation for the same product x Use a product and pass it on (transform) Add objects to the situation X X X x Build on the others’ story X X X X X X X Table 1. Theater techniques that could be used with groups in new product development interactions...september + october 1999 39 ✖ ✖ ✖ ✖ PERMISSION TO MAKE DIGITAL OR HARD COPIES OF ALL OR PART OF THIS WORK FOR PERSONAL OR CLASSROOM USE IS GRANTED WITHOUT FEE PROVIDED THAT COPIES ARE NOT MADE OR DISTRIBUTED FOR PROFIT OR COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE AND THAT COPIES BEAR THIS NOTICE AND THE ✖ FULL CITATION ON THE FIRST PAGE. TO COPY OTHERWISE, TO REPUBLISH, TO POST ON SERVERS OR TO REDISTRIBUTE TO LISTS, REQUIRES PRIOR SPECIFIC PERMISSION AND/OR A FEE. © ACM 1072-5220/99/0900 $5.00 ✖ 40 explore each side of an issue firsthand. We have found that taking turns to convince potential investors helps focus participants to be persuasive rather than being more at odds with one another, as might occur in a courtroom. Alternatively, a courtroom setting could bring out more passionate debates. ✖ Use the same script and change the attitude or emotion. The actor or participants use the same script but change their attitude or their emotions as they play their parts. This technique explores the social range of a situation in which a new product will be introduced. Have the same person play all the roles. Participants can see how roles are affected by new products and vice versa. Act out an everyday situation and add a constraint. Imagine that you are washing a car. Now imagine that you are in the desert and have precious little water and it costs a dollar a gallon. How would you wash your car? If actors are playing the parts, participants could direct the actor’s actions. Act out an everyday situation and add fairy-tale props. Adding fairy-tale props puts the situation in a novel setting, thus emphasizing the interactions. Act out an everyday situation and have a magic wand. By allowing participants to determine what the magic wand changes, researchers can gain insight into the participant’s issues with a new product. Act out what goes on inside a product. This technique reveals participant’s beliefs about a new product. We have found that for software development, this technique helps generate new ideas for icons and for making processes more visible. Imagine an actor or a simple object as the new product. A participant imagines that the actor or simple object is the new product and manipulates the actor or object to get the desired response. This technique reveals how the participant imagines interfacing with the new product. ✖ Change the situation for the same product. Changing the situation helps the researcher understand the social limits of the new product. ✖ Use a product and pass it on (transform). A participant acts out using the product and hands it off to another person, who builds on or finds a new use for the product. We have found that this technique reveals stereotypical uses and actions at first and sometimes leads to novel ways the product can or will be used. ✖ Add objects to the situation. A participant acts out the use of a product; other participants add related products to the situation and begin to use them. This method has the potential to explore the relationship of the new product to other products and environments. ✖ Build on the others’ story. Each participant builds on the previous participant’s story about using a product. This could reveal some unusual scenarios of use. We believe that combining theater techniques and groups promises to be a fertile area for further development. Live theater can create strong shared contexts in which the focus is on interaction, because it is less literal than videos or prototypes. Improvisational theater provides the space for participants to expand and invest themselves in prescribed situations. Both live theater and improvisation can quickly immerse and involve participants in designing new products. We would be glad to hear the successes and challenges that readers have had in developing this approach further. References 1. Bjerknes. G., Ehn, P., and Kyng, M. (eds). Computers and Democracy: A Scandinavian Challenge. Gower Press, VT, 1987. interactions...september + october 1999 2. Boal, A. Games for Actors and Non-Actors (translated Drama to Create Common Context for New Product by A. Jackson). Routledge, London, 1992. Concept End-User Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 3. DeBono, E. Six Thinking Hats. Little Brown and CHI 98 Conference: Human Factors in Computing Company, Boston, MA, 1986. Systems, Los Angeles, CA, April 18 – 23, 1998, p. 251. 4. Greenbaum, J. and Kyng, M. Design at Work: 8. Salvador, T. and Sato, S. Focus Troupe: Mini- Cooperative Design of Computer Systems. Erlbaum, NJ, Workshop on Using Drama to Create Common Context 1992. for New Product Concept End-User Evaluations. 5. Muller, M., Wildman, D., and White, E. Participatory Design Conference, Seattle, 1998. Participatory Design through Games and Other Group 9. Spolin, V. Improvisation for the Theater. Northwestern Exercises. In Conference Companion CHI ’94, Boston, University Press, IL, 1983. MA, April 24 – 28, 1994. 10. Torvinen, V. A Role-Based Design Game: Collective 6. Pogue, D. PalmPilot: The Ultimate Guide. O’Reilly & Reflection and Reconstruction of Computer-Supported Associates, CA, 1998, p. xiii. Work. In Iris 20 Proceedings, Iris 20, Hankø, Norway, 7. Salvador, T. and Howells, K. Focus Troupe: Using August 9 – 12, 1997.