On being Maltese

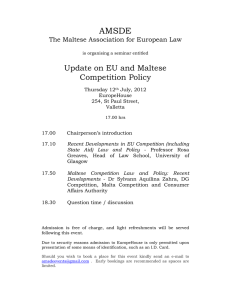

advertisement

THE TIMES, SATURDAY, 28TH JUNE 2008 On being Maltese Henry Frendo Who are the Maltese? What is it to be Maltese? Is it anything at all? Just an accident of birth? I submit that in this day and age the above questions assume a certain urgency. First, Malta is a relatively new state. It has only been independent for 44 years. Italy and Germany, compared to Britain and France, have often been referred to as "new" states because they were only unified in 1870. Indeed, we have even had two correspondents in this newspaper alleging that the Maltese nation did not exist, wondering what there was to "preserve" in it at all ("what, in a jar?", a female columnist for this newspaper once wrote derisively from an English University). More serious has been the allegation by a Maltese sociologist, now living in Canada, to the effect that Malta exists only as a state, not as a nation. His article, first published in England, was later serialised in three parts by this newspaper, and then, after I had questioned its logic, subjected to some face-toface counter-argument by myself in an entire edition of BondìPlus strangely but significantly dedicated to this subject. What does it mean? If a nation does not exist, nor do the Maltese. The nation is the people; not some dynasty, a tract of land or a map. Second, many people may readily assume that they are Maltese. Because they were born here; and/or because they speak Maltese. But many people who are not Maltese are increasingly born here, several of whom may only barely understand Maltese or not at all. Here I am, by force of circumstance, writing in English for a largely Maltese audience. But nationality is not solely and simply about language, although language is a vital carrier and expression of culture in its widest and deepest sense. Our "language question" was never just about language. Third, inter-action with "the other" is changing rapidly, profoundly. In colonial times, the "other" was the ruler, hence it was easier to rally around national symbols, such as the Church, or "our ancient history and monuments" and, above all, to demand civil, political and constitutional "rights", which were generally denied, while economic progress was at best intermittent and geared to "foreign" interests. Once the goal of independence had been finally reached in 1964, and extended to comprise other aspects of it until 1979, the cry was "Europe", in or out or in between. But since the advent of mass tourism in the 1960s, and more so now with the communications revolution, ever-increasing mobility, consumerism and globalisation, EU membership opportunities especially for the younger set, and waves of immigrants filtering in mostly from countries unfamiliar to Malta's past, where does "being Maltese" rest? Who, if anyone, is "the other" now? Have we become "others" to ourselves? Or are the others "us"? Are we sliding out of a cultural matrix to the extent that we had one fixed and firm? Shall we look to nostalgic Maltese emigrants for some solace? A leading author aptly called one of his novels Paceville. Life is now; just do it; but what lurks and lingers beyond cash-and-carry, the push button and the pill? Fourth, 44 years after independence, Maltese history is still not an obligatory subject of instruction in school. Its curriculum frequently changes, expanding, contracting, expanding again, chronological, thematic. The bottom line is that out of the thousands of Maltese students in the secondary school cohort, only some 200 are learning it as an "option", if and when there are enough of them, and providing a teacher becomes feasible. What a disgrace. And that's not to mention public broadcasting, with its evident anti-intellectual bias (witness what became of the animated documentary history L-istorja minn wara l-kwinti, for example). It is a well known principle that people who do not respect themselves will not be respected by others. A well-read lawyer-politician who went on to become head of state once wrote that Malta's greatest enemy was... "l-injoranza" (ignorance). That does not exclude self-identity in time and space. Of course, there are many identities which can also co-exist but what I refer to in particular here is the affinity with community, the sense of belonging to a nation, or not. In other words, not just the family, or the locality, or the church, or the language, but with some or all of those together, and much more, in a recognisably "Eurovision-like" collective sense, as a recognsable, intelligible national self-identity with a loyalty, "pre" and "post" colonial, "pre" and "post" EU, "pre" and "post" mass legal and illegal immigration from all over the place, not just Europe or the Mediterranean, with arrivals possessing languages, religions, mind-sets, lifestyles and histories all their own. All in the pot. Hold it, what pot? Nationality is not spectacle to entertain tourists. Nor is it a political correctness to placate expectations. Nor a sure way of rising to heaven. One challenge is to reach some equilibrium between servilism and parochialism, brouhaha and low self-esteem. Marked traits do lie there. A sense of nationality normally springs from one's very being in shared context over time and memory, however imagined - local, social, gregarious, religious, cultural, habitual, customary, artistic, ethnic, demographic, environmental. It is not a fossil, or it would be dead; but one must be in a position to recognise and to explore its distinguishing marks, its survivalist responses and its creative genius. Otherwise, how and why to relate to one's country? This is a seamless argument: it is neither about fireworks nor about hunting nor about pigeon racing nor about Twisties; it is about all of them, and very much more, in an interactive discourse which should be more structured and instructive. It is what we plan to do at the University by soon launching our new MA in Maltese studies, which has consumed a very full year's preparatory work. In my oration at Sant'Anton on the occasion of the bicentenary of the Dichiarazione dei Diritti degli Abitanti di Malta e Gozo of June 15, 1802, I had launched an appeal for an "Institute of Maltese Studies", which had provoked a supportive bi-party resonance in Parliament and on television. That eventually materialised. The next step is to breathe life into it, which I am confident this course could start to do, complementing a number of IMS doctorates already under way or in the pipeline. This should create a well-spring of persons, not necessarily Maltese persons or even persons of Maltese descent, who would come profoundly and penetratingly, critically and analytically, to appreciate what being Maltese has meant and what it means or does not today, not excluding regional and comparative perspectives. Holistically. A parchment. A landscape. Not sporadic pigeonholed bits and pieces, which do not hang together, not wrapped up in an overlapping resonance and direction. It is necessarily a wide canvas, which some of our very best qualified specialists from different disciplines have agreed to teach and to supervise (there is research component over the part-time three-year span). Other guest speakers will be invited in due course. Topics range from and under the wings of culture and identity to language and ethnicity to theatre and poetry to the natural environment and habitat; urban and rural society, agricultural production and food; parties and governance including decolonisation and devolution, commerce, the dockyard and Services, emigration and migrant settlement, including refugees since the 19th century; religion and secularisation, gender and the family, legal and medical angles; artistic characteristics as expressed in past and present, genres of ethno-music, archaeology and society, the architectural "militarisation of Malta", even inter-related overviews of "Maltese-ness" in philately and numismatics, museums, libraries and archives, thus helping to familiarise students with hands-on research possibilities and methods. For their 25,000-word theses students may pick on any focus, which project will be duly supervised for approach, research and writing skills. Although such an inter-disciplinary initiative cannot redress the curriculum deficit rampant at the scholastic level, I believe it should be, at long last, a "post-colonial" beginning to further a knowledgeable if critical self-awareness and self-appraisal among present and future generations. Not a day too soon. Prof. Frendo is director, Institute of Maltese Studies. henry.frendo@um.edu.mt, maltese-studies@um.edu.mt