Guiding The Way To Waterfront Revitalization Best Management Practices I R S

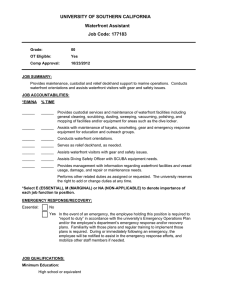

advertisement