London Judgment & Decision Making Group Spring term 2012 – 2013

advertisement

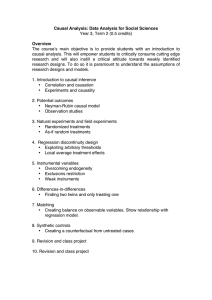

London Judgment & Decision Making Group Spring term 2012 – 2013 Organizers Emmanouil Konstantinidis University College London Contact details: Department of Cognitive, Perceptual & Brain Sciences Room 204c, 26 Bedford Way, London, WC1H 0AP UK Telephone: (+44) 020 7679 5364 E-mail: emmanouil.konstantinidis.09@ucl.ac.uk Neil Bramley University College London Contact details: Department of Cognitive, Perceptual & Brain Sciences Room 201, 26 Bedford Way, London, WC1H 0AP UK E-mail: neil.bramley.10@ucl.ac.uk LJDM website http://www.ljdm.info Web administrator: Dr Stian Reimers (Stian.Reimers.1@city.ac.uk) LJDM announcement emails Contact: Dr Marianne Promberger (marianne.promberger@kcl.ac.uk) Seminar Schedule January – March 2013 5:00 pm in Room 313, 26 Bedford Way, UCL Psychology 9th January The irrationality of categorical perception Steve Fleming New York University and University of Oxford 16th January Multiple developments in children's counterfactual thinking Sarah Beck University of Birmingham 23rd January Limits in decision making arise from limits in memory retrieval Bradley Love UCL, University of London 30th January Children’s causal structure learning Teresa McCormack Queens University, Belfast 6th February An integrative view on algebraic models and heuristics y of risky choice Thorsten Pachur Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin 13th February NO SEMINAR – UCL READING WEEK 20th February Inductive Logic for Automated Decision Making Jon Williamson Kent 27th February Decisions, Variability and Risk Ulrike Hahn Birkbeck, University of London 6th March Criminal Sentencing as a Quasi-rational Cognitive Activity Mandeep Dhami University of Surrey 13th March Does the “Why” Tell Us the “When”? Christos Bechlivanidis University College London 20th March Agency Under Associative Control Robin Murphy University of Oxford Abstracts 09.01.2013 Steve Fleming New York University and University of Oxford The irrationality of categorical perception Categorical perception is ubiquitous in psychology. The perceptual system often settles on one or other interpretation of an ambiguous stimulus, such as a Necker cube, even when a behavioural response is not required. Such categorization is in direct tension with normative decision theory, which mandates that in the face of uncertainty, the utility of various courses of action should be weighted by the agent’s belief in alternate states of the world. If belief is collapsed to a single state, then choices may be suboptimal due to neglecting their costs and benefits under other possible states. We tested for such irrationality in a task that required observers to combine sensory evidence with action-outcome uncertainty. Observers made rapid pointing movements to targets on a touch screen, with rewards determined jointly by uncertainty in stimulus identities and movement endpoints. Across both visual and auditory decision tasks, observers consistently placed more weight on sensory evidence than action consequences. This asymmetry was accounted for by a model in which an internal evidence threshold led to categorical perception on a subset of trials, thus precluding sensitivity to utilities associated with the alternate perceptual state. Our findings indicate that normative decision-making may be fundamentally constrained by the architecture of the perceptual system. 16.01.2013 Sarah Beck University of Birmingham Multiple developments in children's counterfactual thinking The first studies on the development of counterfactual thinking focussed on one question: whether there was a shift in children's speculation about what might have been at 3-4 years of age. Since then findings from a diversity of tasks have suggested that children's abilities develop somewhat earlier (German & Nichols, 2003; Harris, 1997), later (Beck et al., 2006; Rafetseder, CristiVargas, & Perner, 2010), or that the emergence of adult-like counterfactual thinking (e.g. shown by regret) might be separate from the basic reasoning abilities (e.g. Guttentag & Ferrell, 2004; Weisberg & Beck, 2010; in press). I will explore which of the developmental data offer good evidence for counterfactual thinking and identify questions that remain. 23.01.2013 Bradley Love University College London Limits in decision making arise from limits in memory retrieval Do humans and machine systems make difficult decisions in a similar fashion? Some decisions, such as predicting the winner of a baseball game, are challenging in part because outcomes are probabilistic. One view is that humans stochastically and selectively retrieve a small set of relevant memories when making such decisions. We show that optimal performance at test is impossible when retrieving information in this fashion, no matter how extensive training is. One implication of this view of human memory retrieval is that people, unlike machine systems, will be more accurate in predicting future events when trained on idealized than on the actual distributions of items. In others words, we predict the best way to convey information to people is to present it in a distorted, idealized form. Idealization of training distributions is predicted to reduce the harmful noise induced by immutable bottlenecks in people's memory retrieval processes. These conjectures are strongly supported by several studies and supporting analyses. People's test performance on a target distribution is higher when trained on an idealized version of the distribution than on the actual target distribution. Optimal machine classifiers modified to selectively and stochastically sample from memory match the pattern of human performance. These results have broad implications for how to train humans tasked with important classification decisions, such as radiologists, baggage screeners, intelligence analysts, and gamblers. 30.01.2013 Teresa McCormack Queen’s University, Belfast Children’s causal structure learning In a series of studies, we have examined children’s ability to learn the structure of simple threevariable mechanical causal systems. We have found that children seem to have difficulty using statistical information to learn causal structure, whether this is provided through observation of the operation of a probabilistic system or through demonstrating the effects of interventions on the system. Children, and in some cases adults too, are likely to rely on simple temporal cues to make such judgments, even when this conflicts with statistical information. Children also have difficulty predicting the effects of interventions on a causal system even if they are explicitly told its structure. These findings are not straightforwardly predicted by the Causal Bayes Net account of children’s causal structure learning. 6.02.2013 Thorsten Pachur Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin An integrative view on algebraic models and heuristics of risky choice Two prominent approaches to describe how people make decisions between risky options are algebraic models and heuristics. The two approaches are based on fundamentally different algorithms and thus are usually treated as antithetic, suggesting that they might be incommensurable. Using cumulative prospect theory (CPT; Tversky & Kahneman, 1992) as an illustrative case for an algebraic model, we demonstrate how algebraic models and heuristics can mutually inform each other. Specifically, we highlight that CPT characterizes decisions in terms of psychophysical characteristics (e.g., diminishing sensitivity to probabilities and outcomes) and descriptive constructs such as risk aversion and loss aversion, and we argue that this holds even when the underlying process is heuristic in nature. Fitting CPT to choices generated by various heuristics, we find (a) that CPT is able to represent choices generated by heuristics with a good model fit; and (b) that the heuristics generate characteristic parameter profiles in CT that reflect the process architectures of the different heuristics in a psychologically meaningful way. Using this approach we illustrate how CPT can be used to track how a heuristic’s degree of risk aversion changes across different environments. Despite CPT’s ability to accommodate heuristic choices rather well, model recovery analyses showed that the heuristics and CPT can still be well distinguished under reasonable amount of noise in the data. Our results demonstrate that algebraic models and heuristics offer complementary rather than rival modeling frameworks and highlight the potential role of heuristic principles in information processing for prominent descriptive constructs in risky choice. 20.02.2013 Jon Williamson University of Kent Inductive Logic for Automated Decision Making According to Bayesian decision theory, one's acts should maximise expected utility. To calculate expected utility one needs not only the utility of each act in each possible scenario but also the probabilities of the various scenarios. It is the job of an inductive logic to determine these probabilities, given the evidence to hand. The most natural inductive logic, classical inductive logic, attributable to Wittgenstein, was dismissed by Carnap due to its apparent inability to capture the phenomenon of learning from experience. I argue that Carnap was too hasty to dismiss this logic: classical inductive logic can be rehabilitated, and the problem of learning from experience overcome, by appealing to the principles of objective Bayesianism. I then discuss the practical question of how to calculate the required probabilities and show that the machinery of probabilistic networks can be fruitfully applied here. This culminates in an objective Bayesian decision theory that has a realistic prospect of automation. 27.02.2013 Ulrike Hahn Birkbeck, University of London Decisions, Variability and Risk The talk examines critically whether Expected Utility theory, the dominant normative framework for the evaluation of decisions within philosophy, psychology, and economics deals appropriately with variability or risk. It may be argued that the axiomatic foundations of utility theory provide insufficient grounds for acceptance as a normative framework, in particular in contexts of highly skewed distributions and one-off gambles. Simulation results aimed at the question of whether alternative strategies may fare equally well or better under such circumstances will be discussed and related to psychological data. 06.03.2013 Mandeep Dhami University of Surrey Criminal Sentencing as a Quasi-rational Cognitive Activity Criminal sentencing is a complex cognitive activity that is often performed under suboptimal conditions. It requires judges to apply intuitive and analytic judgment. Evidence suggests that sentencers may not behave according to legal policy and training, and so several jurisdictions have introduced guidelines to aid sentencing practice. I present recent research demonstrating that sentences meted out in real cases are not being tailored to fit the characteristics of the individual offence and offender, and that both the existing and new guidelines may be ineffective in helping sentencers achieve this goal. Sentencing is not an intractable problem, and I propose the design of more precise and comprehensive flowchart-type guidelines. However, this requires making our notions of justice and fairness explicit and defining the concept of quasi-rationality. 13.03.2013 Christos Bechlivanidis University College London Does the “Why” Tell Us the “When”? Traditional approaches to human causal judgment assume that the perception of temporal order informs judgments of causal structure. We present two experiments where people follow the opposite inferential route, where perceptual judgments of temporal order are instead influenced by causal beliefs. By letting participants freely interact with a software-based “physics world”, we induced stable causal beliefs that subsequently determined participants’ reported temporal order of events, even when this led to a reversal of the objective temporal order. We argue that for short timescales, even when our temporal resolution capabilities suffice, our perception of temporal order is distorted to fit existing causal beliefs. 20.03.2013 Robin Murphy University of Oxford Agency Under Associative Control Current research exploring the causes of volition argue for a ‘neurodualism’ in which the classic distinction between instrumental action and Pavlovian reflex is found in separate neural pathways. This endeavour pushes the causal mystery of voluntary behaviours around the brain without necessarily developing our understanding of how the decisions related to voluntary actions emerge. Associative learning mechanisms suggest that, at least part of, our sense of agency is the product of a competitive learning network. Several experiments in which participants are required to learn to control the occurrence of a novel outcome are described exploring 1) how perceptions of control seem to emerge from learning processes and 2) that even with the same learning experience individuals vary in how agentic they feel. This variability might be due to cognitive processes correlated with mood state. Two interference experiments one using a neuroinhibitor (Chase et al., 2011) and another a neuroenhancer (Msetfi et al., in prep) illustrate the role of the serotonergic pathways for learning and our perception of agency.