Document 13129225

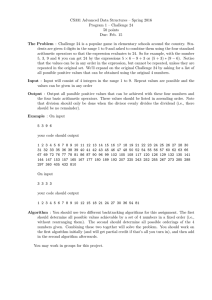

advertisement