Measuring the Impact of the ‘Two Hours/Two Periods Final Report

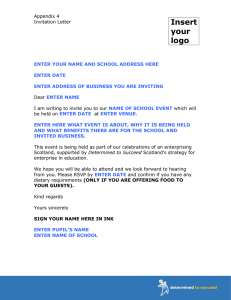

advertisement