BETER W E C A N D O

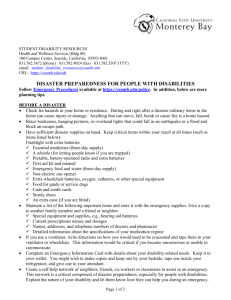

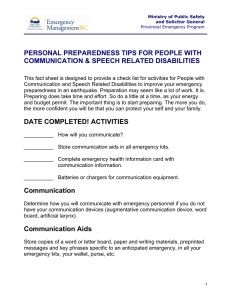

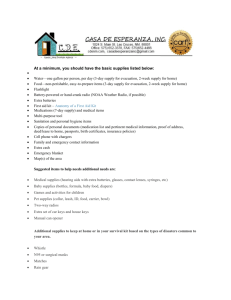

advertisement