The Great Depression: getting the story right

advertisement

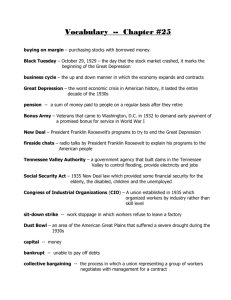

The Great Depression: getting the story right Nicholas Crafts and Peter Fearon Although the implications of the economic history of the period for preventing recession turning into depression are well known and have been acted on in the current crisis, there are important aspects of the recovery phase of the 1930s that deserve greater prominence in today’s policy debates. First, it is important to recognise that fiscal policy did not fail in the 1930s. Rather it was not really tried until very late in the day in the context of rearmament. The New Deal was certainly not a Keynesian policy package. The evidence is that the multiplier effects of fiscal stimulus both in Britain and the United States were quite sizeable, as might be expected when interest rates were very low. Second, fiscal consolidation to address issues arising from government budget deficits stemming from the crisis was attempted in many countries. The experience of the 1930s underlines that if this was not to be dangerously deflationary it was vital that monetary policy was expansionary, as in Britain after 1932. The key requirement was that real interest rates were reduced by policies that made people think that in future prices would be rising not falling. Lesson: An implication for today is not only that quantitative easing is likely to be an important underpinning for fiscal consolidation but also that it may be appropriate to revise inflation targets of central banks upwards. Third, the largely-forgotten US recession of 1937/8, when in the middle of an apparently strong recovery real GDP fell by 10 per cent, underlines the risks of seeking to return to a balanced budget while simultaneously tightening monetary policy. Lesson: Avoiding a double-dip recession in the context of fiscal consolidation following a serious financial crisis is not a done deal unless central banks can keep real interest rates low, which the Fed signally failed to do in 1937. Fourth, the most striking feature of the 1930s is that countries that stayed on the gold standard were locked into a deflationary spiral that kept real interest rates high, prevented independent use of monetary policy, and made the arithmetic of tackling budget deficits much more unpleasant. Lesson: A very clear message of the 1930s experience is that leaving the golden fetters of the fixed exchange rate system was a key to recovery (as in both the United States and the UK). This is the classic escape route, which is denied to today’s members of the Eurozone and in the absence of which the prospects for economies like Greece look bleak indeed. ENDS Coping with financial crisis: the US in the 1930s Price Fishback Monetary and fiscal policy contributed to making the Great Depression worse. Between 1929 and 1933 the Federal Reserve focused on maintaining the international gold standard. Fed policy-makers thought they had stimulated activity by lowering the discount rate but did not recognise that the substantial deflation had raised the real discount rate above 10%. The economy started to recover when the US left the gold standard and expanded the money supply. After the Fed raised reserve requirements in 1936 and 1937, the economy contracted sharply a second time. Increases in tariffs, income tax rates, and excise taxes also contributed to the contraction. Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt both increased federal spending a great deal, but taxes rose nearly as fast. Thus, the federal deficit remained small, and a Keynesian expansionary policy was not attempted. In response to the 2007-09 Great Recession, the Fed and the US Treasury quickly bought bonds, took ownership stakes in banks and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and provided financial guarantees. The 2009 stimulus package led to federal deficits as a share of GDP that are nearly twice as high as any peace-time deficits in American history. The deficit response looks like the type of Keynesian response one might have expected for the Great Depression, while the response in the 1930s looked more like the type of response one would have anticipated to the modern recession. ENDS Depression and recovery in 1930s Britain Roger Middleton Today’s policy-makers need to be aware of key messages from British experience in the depression. These relate in particular to fiscal policy and arise from the attempts made by the British governments of the time to return to balanced budgets in the face of a severe downturn in the economy. First, budget deficits rise as recession takes hold reflecting the operation of the ‘automatic stabilisers’ (transfer payments such as unemployment benefits increase and tax revenues decrease), which cushion the economy to some extent from the effects of the downturn. In 1931/2, the British government alarmed by deteriorating public finance acted to override the automatic stabilisers through deflationary budgets, which hit the economy hard. This mistake was not repeated by the outgoing Labour administration in the present crisis with the inevitable result that public borrowing rose very rapidly. This should not be seen as a failure but an appropriate response to the financial crisis. Second, fiscal consolidation in the early 1930s did not ultimately prevent a rapid recovery in Britain after 1932, which saw growth average 4% per year over the following five years. The reason for this was that Britain left the gold standard, cut nominal interest rates and rekindled expectations of mild price inflation rather than falling prices. In other words, monetary policy was able effectively to offset the deflationary impact of fiscal stringency. The successful outcome was as much good luck as well-designed policy especially since in 1930s conditions the multiplier effects of fiscal contraction were relatively large. A key question for today is whether the Bank of England will be able to underpin the economy as expenditure cuts and tax increases take effect. The likelihood is that in order to do so, the Bank will have to accept the inflationary risks of continuing its policies of quantitative easing in order to keep real interest rates very low and that Mervyn King will find himself writing a long series of letters to George Osborne explaining why the inflation target has been missed. ENDS