What works in character education: A research-driven guide for educators

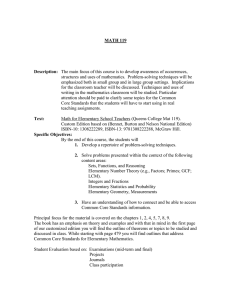

advertisement