Political Representation and Crime: Evidence from India’s Panchayati Raj October 2009

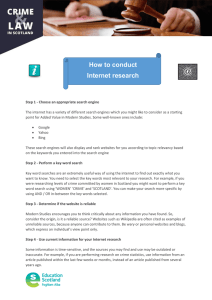

advertisement