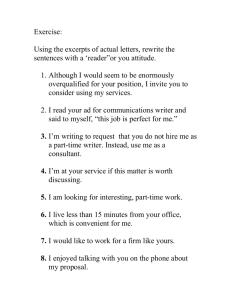

extra ”It’s like seeing a whole other

advertisement