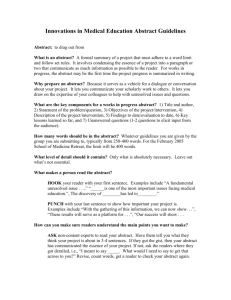

Writing the Empirical Journal Article

advertisement