Career Guidance Policies: Global Dynamics, Local Resonances www.derby.ac.uk/icegs/

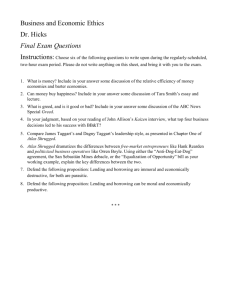

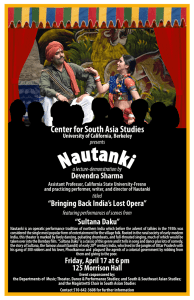

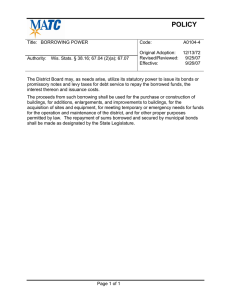

advertisement