SYMPOSIUM ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT MEETINGS PHILADEPHIA AUGUST 3-8, 2007

advertisement

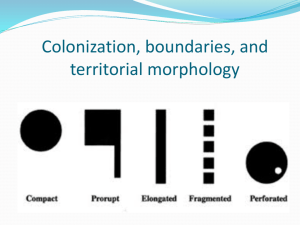

11212 SYMPOSIUM ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT MEETINGS PHILADEPHIA AUGUST 3-8, 2007 Program Session #: 796 (OCIS, OB) Scheduled: Monday, Aug 6 2007 12:20 PM – 2:10 PM Philadelphia Marriott: Room 405 COORDINATION COMPLEXITY IN GEOGRAPHICALLY DISTRIBUTED COLLABORATION Co-Chairs and Presenting Authors: Presenting Authors: Robert M. Verburg Organizational Behaviour and Innovation Delft University of Technology Jaffalaan 5, 2628 BX Delft, The Netherlands Phone: +31 15 2787234 Fax: +31 15 2782950 Email: r.m.verburg@tudelft.nl Deanne N Den Hartog Dept of Management and OB Universiteit van Amsterdam Business School Roeterstraat 11, 1018 WB Amsterdam The Netherlands Phone: +31 205255287 Fax: +31 205255281 Email: d.n.denhartog@uva.nl J. Alberto Espinosa Kogod School of Business American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016-8044 Tel. 202.885.1958 Fax. 202.885.1992 Email: alberto@amercian.edu Joachim Schroer Department of Psychology University of Wuerzburg Roentgenring 10 D-97070 Wuerzburg Germany Phone: (+49) 931 31 6062 Email: schroer@psychologie.uni.wuerzburg.de Discussant: Pamela J. Hinds Center for Work, Technology, and Organization Management Science and Engineering Stanford University Tel 650-723-3843 Email: phinds@stanford.edu 1 Kevin Crowston School of Information Studies Syracuse University Tel (315)443-1676 Email: crowston@syr.edu 11212 Co-Authors: Anne E. Keegan Dept of Management and OB Universiteit van Amsterdam Business School Roeterstraat 11 1018 WB Amsterdam Phone: 0031 205255287 Fax: 0031 205255281 Email: A.E.Keegan@uva.nl Matti Vartiainen Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Laboratory of Work Psychology and Leadership, PO Box 5500 FI-02015 TKK, FINLAND matti.vartiainen@tkk.fi, Guido Hertel Department of Psychology University of Wuerzburg Roentgenring 10 D-97070 Wuerzburg Germany Phone: (+49) 931 31 6060 Email: hertel@psychologie.uni.wuerzburg.de William DeLone Kogod School of Business American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016-8044 Tel. 202.885.1958 Fax. 202.885.1992 Email: wdelone@amercian.edu Petra Bosch-Sijtsema Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Laboratory of Work Psychology and Leadership, PO Box 5500 FI-02015 TKK, FINLAND Petra.Bosch@petrabosch.com Gwanhoo Lee Kogod School of Business American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016-8044 Tel. 202.885.1958 Fax. 202.885.1992 Email: glee@amercian.edu 2 11212 ABSTRACT Globalization trends have increased the popularity of geographically distributed collaboration and virtual teams. The potential benefits of working across virtual team boundaries abound, but they come at substantial coordination costs, particularly when geographic configurations and team tasks are flexible and complex. While research in this area has flourished, we still don’t understand what the net benefits of geographically distributed collaboration are, once all the respective coordination costs have been accounted for. Consistent with the conference theme “doing well by doing good”, and to bring together multiple perspectives on coordination benefits and costs in geographically distributed collaboration, we have put together a collection of current research for this symposium. The contributions are from European and US scholars with recognized expertise in research on coordination and geographically distributed teams. The symposium aims to discuss the complexities of coordinating work across multiple virtual team boundaries, and to bring together various perspectives on the respective coordination benefits and costs in this context. Divisions: Key Words: Organizational Behavior, Organizational Communication & Information Systems Organizational Communication & Information Systems – Virtual Teams, Coordination, Virtual Leadership Organizational Behavior – group/team (characteristics, processes), Leadership, Technology 3 11212 COORDINATION COMPLEXITY IN GEOGRAPHICALLY DISTRIBUTED COLLABORATION ROBERT M. VERBURG AND J. ALBERTO ESPINOSA Symposium Overview Global market developments and the large-scale use of diverse applications in the area of information and communication technology have been key factors in the popularity of geographically distributed collaboration, often carried out by virtual teams. Virtual teams enable collaboration between people across traditional boundaries of time and place and offer tremendous opportunities for various collaborative achievements. Organizations are no longer tied to a single time location or time zone to conduct business and are able distribute task activities to have easy access to clients and/or expertise, and in some cases take advantage of time zone differences to carry out work activities like software development around the 24-hour clock. The Internet as the almost universal medium for interaction across boundaries has created an infrastructure that enables many organizations to launch virtual teams. However, despite the potential benefits of geographically distributed collaboration, there is often substantial coordination overhead associated with the complexity of the team’s geographical configuration. Therefore, the costs and benefits of distributed collaboration need to be carefully evaluated because what may appear to be a big advantage (e.g., ability to work on a task around the clock, cheaper labor rates in outsourcing arrangements) may end up causing substantial disadvantages (e.g., high coordination costs, increased effort, team member burnout). 4 11212 Technical obstacles for communication and collaboration across geographic boundaries remain, as virtual team processes are supported by collaboration technology solutions, such as groupware and other collaborative applications (e.g. videoconferencing, electronic blackboards). Furthermore, these more fluid and virtual work environments create new challenges for managers, who can no longer literally ‘oversee’ subordinates’ efforts. Observing, monitoring and controlling, in other words direct supervision of tasks performed at various locations is no longer possible. Thus, several questions remain unanswered: how then do managers lead and coordinate subordinates’ efforts? How are organizational and technological changes affecting the process of management at the group level? What are the complexities of collaborating in geographically dispersed configurations? Which other discontinuities besides virtual team boundaries must be overcome in order to coordinate effectively? This symposium addresses these questions through presentations of recent research on leadership and coordination mechanisms within the context of such complex virtual teams. Our proposed symposium contributes to the conference theme “doing well by doing good” by showing that that traditional perspectives on coordination and performance indicators do not suffice in virtual contexts, as output measures often includes both transactional and voluntary actions of collaborating members of virtual teams. In geographically distributed collaboration, what may appear to be beneficial – e.g., coordination effectiveness, reduced production costs, access to expertise and global markets, round-the-clock production, etc. – may carry substantial costs when all aspects of coordination are considered – e.g., additional coordination costs, increased effort, weaker shared mental models, diminished ability to lead team members, team member burnout, etc. To bring together these multiple perspectives, we have solicited papers for this symposium from both, European and US scholars with recognized expertise in research on coordination and geographically distributed teams. We have asked 5 11212 authors to contribute presentations that highlight their recent work focusing on two things about geographically distributed collaboration: (1) the complexities of coordinating work; and (2) the various aspects of coordination benefits and costs that need to be taken into account. The proposed symposium will be a presenter symposium chaired by Alberto Espinosa and Robert Verburg. They will begin the session by discussing current trends in collaboration across geographical boundaries and the ensuing demands on leaders. Following the session introduction, each of the following authors will present a summary of their research. The Crowston paper examines factors affecting the relationship between virtual work settings and work outcomes. The authors present a model of virtual work that differentiates between boundaries and discontinuities. The importance of shared mental models for virtual team coordination is highlighted in this discussion. A common research strategy for research on virtual work has been to compare virtual work to non-virtual work. In order to move beyond “either-or” dichotomies, several researchers have adopted the concept of boundaries to characterize the multiple dimensions of virtuality. Boundaries are the “often imaginary lines that mark the edge or limit of something”. In addition to boundaries, a number of researchers have identified discontinuities such as relationship with an organization (e.g., permanent vs. selfemployed or temporary worker) and task. This paper shows the importance of looking more closely at the process of working virtually to understand how it is actually experienced by virtual workers. Den Hartog and Keegan examine the limits to leadership in virtual contexts. Their empirical work explores the changing role of leaders and the challenges that leaders face in more organic, flexible and virtual contexts. While managers’ indicate that strong leadership is needed in these contexts, many barriers exist. Such distal and virtual managers often experience ambiguity in reporting relationships, are often less able to exercise the same influence over 6 11212 performance evaluation and careers, and less easily influence identification and trust as compared to their co-located counterparts. If this is the case, the enthusiasm with which some writers embrace the possibilities offered by more virtual, temporary, and flexible ways of organizing may need to be tempered by the possibility that such work arrangements strain crucial leader-follower relationships. Den Hartog and Keegan’s work contributes to the symposium by examining these limitations of effective leadership in distributed contexts. The paper by Schroer and Hertel provides an empirical assessment of voluntary engagement of actors in an open web-based encyclopedia. Founded in January 2001, Wikipedia has quickly become one of the 15 most popular websites worldwide and attracts more than 154 million visitors per month. As volunteers, many contributors invest a considerable amount of time into researching and writing articles or maintaining the technical infrastructure without receiving any financial compensation for their efforts. Little is known about the motivation of its contributors. This study shows that the three most prominent categories of motives suggested by Wikipedia contributors in the open questions were related to task enjoyment, information sharing and generativity motives. The results both have implications for how to improve motivation and contribution in Internet communities. The Verburg, Bosch-Sijstma and Vartiainen paper examines why project managers are willing to work in fully virtual settings. More and more research is performed on work in (to some extent) virtual settings; however, few empirical studies discuss collaboration in fully virtual settings in which no face-to-face contact is present. Furthermore, the reasons why project managers are willing or are not willing to participate in fully virtual settings have not yet received attention in research. The authors investigate which attributes (conditions of fully virtual settings) increase decision-makers’ willingness to work in fully virtual projects, what the perceived benefits of doing so are and which personal values lay behind the decisions to work 7 11212 virtually. Among other things, this study shows that accomplishment is an important value for project managers and this is achieved by benefits of efficiency and conditions in virtual projects of corporate support, clear communication rules and trust. This paper provides insight in the motivation of managers themselves in such complex, virtual environments. Espinosa, Lee and Delone propose a construct for virtual team boundary complexity in order to get a better understanding of virtual team coordination. Coordination is about managing dependencies among task activities. However, it are not the virtual team boundaries themselves that make it more difficult to manage these dependencies, but the complexity of the virtual team boundary configuration resulting from having to work across multiple boundaries. Therefore, understanding this complexity is very important in figuring out how virtual teams can coordinate their work more effectively. The authors draw upon data collected by themselves and colleagues for two different research projects to support our arguments. They argue that the overall communication effectiveness in the team and, therefore, its ability to coordinate “organically” will generally be affected by the complexity of the team’s geographic configuration – i.e., number of different of types and number of boundaries spanned by the team, the alignment of these boundaries and the dispersion of members across them. Pamela Hinds, a world-renowned authority on the effects of technology on groups and teams will serve as the session discussant. Dr. Hinds has authored several books and articles addressing the effect of geographic distribution on work teams, cognitive and motivational inhibitors to using and sharing expertise, and the effects of autonomous mobile robots in the work environment, including workers' responses. Dr. Hinds will share her evaluation of the research presented and suggest directions for future research and theory for coordination mechanisms for geographically distributed groups. 8 11212 RELEVANCE OF THIS SYMPOSIUM TO THE SELECTED DIVISIONS This symposium is proposed for the Organizational Behavior, and Organizational Communication & Information Systems Organizational Behavior: The Organizational Behavior division describes its domain as the study of individuals and groups within an organizational context, and includes leadership and group processes among its topics of interest. As the papers in this symposium addresses effective leadership of and within virtual teams, the symposium’s theme is aligned well with the division’s mission. Organizational Communication & Information Systems. The Organizational Communication & Information Systems division describes topics relevant to its mission as addressing: the study of behavioral, economic, and social aspects of communication and information systems within and among organizations or institutions. As the symposium addresses coordination mechanisms for virtual teams, the symposium is well aligned with the division’s objectives. We have received signed statements from all intended participants formally agreeing to participate in the symposium 9 11212 COORDINATING ACROSS BOUNDARIES AND DISCONTINUITIES KEVIN CROWSTON Syracuse University, School of Information Studies Work has become increasingly virtual as diverse forms of electronic communication have become ubiquitous in the workplace. However, our understanding of the consequences and implications of virtual work lags its implementation. A particular problem for research is understanding why seemingly similar virtual settings can have different consequences for the coordination of virtual teams. To address this question, we differentiate between the effects of boundaries and discontinuities (two common conceptualizations of virtuality). A number of researchers have adopted the concept of boundaries to characterize multiple dimensions of virtuality. Boundaries are the “often imaginary lines that mark the edge or limit of something” (Espinosa et al., 2003). Distance is the most obvious boundary that is encountered in virtual work but the point of this argument is that people working virtually encounter numerous boundaries that are not present to the same extent in conventional work settings. Espinosa et al. (2003) found five boundaries in studies of field-based virtual teams: geographical, functional, temporal, organizational and identity (team membership). Orlikowski (2002) found boundaries to be particularly important in understanding how work was conducted in a geographically dispersed high tech organization. She identified seven boundaries that “members routinely traverse in their daily activities” (p. 255): temporal, geographic, social, cultural, historical, technical and political. However, characterizing virtual settings in terms of boundaries provide only a partial description of the complexities of virtual work. In particular, boundaries are usually seen as being fixed and objective—geography is geography, distance, distance—yet their effects may differ from group to group or even within the same group over time. For example, Orlikowski (2002) notes that the members of the organization she studied adapted their behaviors regularly in order to deal with the multiple boundaries they encountered in their daily work activities, as 10 11212 the meaning of the boundaries were “reconstructed and redefined” (p. 11). To understand these variable effects, we need a deeper examination of the effects of boundaries on coordination. To conceptualize coordination across boundaries, Watson-Manheim, Chudoba and Crowston (Under review) drew on Nijkamp, Rietveld & Salamon’s (1990) analysis of the effects of borders on physical flows of goods. Those authors noted that the existence of a border creates a discontinuity in the marginal cost of such flows at the point where they cross a border. For example, moving products from one country to another may incur costs due to waiting time and administrative activities at the border. The result is a discontinuity in costs, which rise smoothly with increased distance but jump discontinuously at the border, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1. A border creates a discontinuity in the cost of transport. Applying this model to a virtual work setting, boundaries may pose difficulties that increase the effort needed to coordinate work, thus posing discontinuities in the cost of coordination. In this case, the boundary implies differences that must be articulated, negotiated and resolved, leading to a rise in coordination costs. However, not all boundaries create discontinuities. For example, the boundary between two US states is still a boundary, but generally poses little or no discontinuity in the cost of transport. Similarly, boundaries in virtual work may or may not create coordination problems for workers. Therefore, we turn next to the question of why some boundaries may create problems for coordination while others do not. Previous research has noted that while distance objectively exists as a boundary between virtual team members, the actual effect that distance has on coordination of work activities depends on 11 11212 how it is perceived by the team members. Espinosa et al. (2003) found that “prior knowledge of colleagues and contexts across sites offset many of the problems with distance” (p. 163), indicating that negative effects of distance may be mitigated by experience. More specifically, we suggest that discontinuities arise when expectations of the joint work are not met, creating the need for additional work to make sense of a confusing situation. Expectations can be understood as part of an individual’s mental model of the situation, an internal representation of reality that guides thinking and acting (Spender, 1998). The role of expectations is critical to organizational functioning as they allow individuals to assume different roles while still adopting their activities and meanings appropriately for the situation (House et al., 1995). In addition, expectations enable individuals to deal with ambiguity in well-practiced ways by associating them with prior experiences, and therefore enabling them to predict what should happen next (Matlin, 1998). Furthermore, humans experience the world with others, sharing and interpreting common experiences. As Schutz and Luckman (1973) put it, “The life-world is not my private world nor your private world, nor yours and mine added together, but rather the world of our common experience.” (p. 68). Therefore, the expectations of the joint work have to be shared to be effective. Research suggests that shared mental models help improve performance in face-to-face (Rentsch & Klimoski, 2001) and distributed teams (Sutanto et al., 2004). Without shared mental models, individuals from different teams or backgrounds may interpret tasks differently based on their individual backgrounds, making collaboration and communication difficult (Dougherty, 1992). The tendency for individuals to interpret tasks according to their own perspectives and predefined routines is exacerbated when working in a distributed environment, with its more varied individual settings. On the other hand, well-developed shared mental models can enable teams to coordinate their activities without the need for explicit communications (Crowston & Kammerer, 1998; Espinosa et al., 2004). For example, Crowston & Kammerer (1998) describe how the development of “collective mind” supported coordination of requirement analysis in software requirements analysis. Of course, some effort will always be needed to coordinate 12 11212 work, but with a well-developed set of shared expectations, the effort may be comparable in both virtual and conventional groups. To develop shared expectations, more than communications is needed. As Boland and Tenkasi (1995) put it, “the problem of integration of knowledge in knowledge-intensive firms is not a problem of simply combining, sharing or making data commonly available. It is a problem of perspective taking in which the unique thought worlds of different communities of knowing are made visible and accessible to each other” (p. 359). As differences emerge, communication partners need to have enough common ground to quickly negotiate differences without perceiving extraordinary effort. For example, Katzy & Crowston (2000) found a shared national culture and shared professional culture held a virtual group together so that it could function successfully. Similarly, Kumar et al. (1998) found that standardized supply chain management procedures and a strong social network substituted for what would have been in place if all production had been done in one company. The role of shared mental models in shaping discontinuities in virtual work can be seen in the setting of Free/Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) development. Most FLOSS software is developed by dynamic self-organizing distributed teams comprising professionals, users and other volunteers working in loosely coupled teams. These teams are close to pure virtual teams in that developers contribute from around the world, meet face-to-face infrequently if at all, and coordinate their activity primarily by means of computer-mediated communications (CMC). The literature on software development emphasizes the difficulties of distributed software development, but the apparent success of FLOSS development presents an intriguing counterexample. We argue that while the work of FLOSS developers is characterized by many boundaries (space, time, organization, national culture, language among others), but few discontinuities because of the understandings of the work shared by the developers. In summary, while boundaries will always be present in virtual work, discontinuities may come and go. Research on virtual work therefore needs to look deeper to determine how or if the 13 11212 apparent borders are problematic to the coordination of work. Furthermore, research should recognize that what is problematic at one point in time may not always be so. Therefore, it is important to look more closely at the process of coordinating virtual work to understand how it is actually experienced by those workers. References Boland, R. J., & Tenkasi, R. V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organization Science, 6(4), 350–372. Crowston, K., & Kammerer, E. (1998). Coordination and collective mind in software requirements development. IBM Systems Journal, 37(2), 227–245. Dougherty, D. (1992). Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms. Organization Science, 3(2), 179–202. Espinosa, J. A., Cummings, J. N., Wilson, J. M., & Pearce, B. M. (2003). Team boundary issues across multiple global firms. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 157– 190. Espinosa, J. A., Lerch, F. J., & Kraut, R. E. (2004). Explicit versus implicit coordination mechanisms and task dependencies: One size does not fit all. In E. Salas & S. M. Fiore (Eds.), Team cognition: Understanding the factors that drive process and performance (pp. 107-129). Washington, DC: APA. House, R., Rousseau, D. M., & Thomas-Hunt, M. (1995). The meso paradigm: A framework for the integration of micro and macro organizational behavior. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 17, pp. 71–114). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Katzy, B. R., & Crowston, K. (2000). A process theory of competency rallying in engineering projects. Munich, Germany: CeTIM. Kumar, K., van Dissel, H. G., & Bielli, P. (1998). The Merchant of Prato revisited: Towards a third rationality of information systems. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 22(2), 199–226. Matlin, M. W. (1998). Cognition. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Brace, & Company. Nijkamp, P., Rietveld, P., & Salomon, I. (1990). Barriers in spatial interactions and communications: A conceptual exploration. Annals of Regional Science, 24(4), 237–252. Orlikowski, W. J. (2002). Knowing in practice: Enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organization Science, 13(3), 249–273. Rentsch, J. R., & Klimoski, R. J. (2001). Why do ‘great minds’ think alike?: Antecedents of team member schema agreement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(2), 107–120. Schutz, A., & Luckman, T. (1973). The Structures of the Life-World (R. M. Zaner & H. T. Engelhardt, Jr., Trans. Vol. 1). Evanston: Northwestern University. Spender, J.-C. (1998). The dynamics of individual and organizational knowledge. In C. Eden & J.-C. Spender (Eds.), Managerial and organizational cognition: Theory, methods and research (pp. 13–39). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sutanto, J., Kankanhalli, A., & Tan, B. C. Y. (2004). Task coordination in global virtual teams. Paper presented at the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Information Systems, Washington, DC. Watson-Manheim, M. B., Chudoba, K. M., & Crowston, K. (Under review). Distance Matters, Except When It Doesn’t Academy of Management Conference. Philadelphia, PA. 14 11212 LEADING IN VIRTUAL CONTEXTS DEANNE N. DEN HARTOG AND ANNE E. KEEGAN University of Amsterdam Globalization and the developing information technology are enhancing the need for and possibilities of virtual collaboration. Virtual work is often performed in teams that come in many forms, with differing objectives, membership criteria, and levels of dispersion or diversity (Zigurs, 2003). However, working virtually also often implies more flexible, adaptive or projectbased structures; in other words, organizational structures that are more complex and “organic” (cf. Burns & Stalker, 1961). Leaders in these settings can no longer literally ‘oversee’ subordinates’ efforts. Observing, monitoring, and controlling, in other words direct supervision of tasks performed at various locations at different times is difficult (Den Hartog & Koopman, 2001). The research presented here explores the changing role of leaders and the challenges that leaders face in more organic, flexible and virtual contexts. What is the role of leaders? As organizations increasingly rely on temporary arrangements, such as project teams working together virtually for a specific task for a limited duration, leadership may also become a temporary arrangement. Any member with relevant knowledge and experience could lead a specific project and people may work in multiple teams simultaneously, as leader in one and as member on another. The leadership role may also be divided and performed by many or all team members simultaneously or sequentially, as suggested in self-management or shared leadership models (e.g. Barker, 1993). The increasing use of computer-mediated technologies may emphasize cognitive elements of the leadership role (e.g. managing information flow) and reduce social/emotional elements (Shamir, 1999). The study among managers in different virtual, complex, and project-oriented firms presented in this 15 11212 paper suggests problems with these scenarios, including the potential for conflicting demands, role ambiguity, and issues around ensuring sufficient identification. For example, in our qualitative study we find that having multiple different (virtual) leaders may place conflicting or unclear demands on employees. Our interviewees describe that when people report to multiple leaders performance evaluation can be difficult (this held both for having different virtual leaders or other combinations, such as a virtual project manager and a colocated line manager). The information available for evaluating performance at a distance is limited. Criteria for performance evaluation may be ambiguous if multiple leaders are involved and who should evaluate employees’ performance may also be unclear in virtual, often projectoriented structures. For example, a manager of a world-wide IT firm indicates that in their virtual teams it is often the local managers who do the performance evaluations whereas their employees work for multiple international projects and project managers are the ones doing the day-to-day management. Similarly, a manager of one of the companies involved in the project organization formed to build a high-speed train network explains that in this organization, workers report to a project manager who leads them on a day-to-day basis. Although the employees do not necessarily see their line manager at the mother company at all, performance evaluations, training needs analyses, and career decisions mainly remain the responsibility of their ‘home’ company line manager. A related risk that is sometimes mentioned is that when employees become involved in too many different virtual teams at the same time they may become less and less visible for management. Managers indicate that in a virtual context, people working in multiple teams can often more easily hide from their (team) responsibilities if they choose to do so, as virtual meetings are generally limited to one-hour conference calls. In other words, managers experience problems with their lack of direct supervision. Complicating factors the managers mention 16 11212 include that virtual work often involves people from different countries working together (which means that ambiguities due to language problems and cultural differences regularly occur) and that the leader often has not personally selected (international) team members. For example, in the aforementioned IT firm, international teams tend to be formed without the leader’s involvement in the selection of the members from other countries. This may hinder the development of trust and increase ambiguity about reporting relationships. The literature suggests a crucial role for trust-building and identification processes at work. Identifying with a group implies adherence to a pattern of values shared within such a group. Having a sense of belongingness increases commitment to a group and its goals and with that enhances a willingness to go the extra mile for the group (e.g. Den Hartog, De Hoogh & Keegan, 2007). In other words, identification with a group raises effort people are willing to take on behalf of the group. However, creating belongingness and identification is important but problematic in virtual and flexible settings and belonging to multiple, temporary groups with unclear boundaries may lead to identity problems, reduced commitment and reduced willingness to take on extras or help others. In the project organization working on the high-speed link, managers want workers to identify with the project organization itself as well as the respective ‘home’ companies to which different workers return once their part of the job is done. The managers find that the latter can be difficult when project workers don’t have any tangible link to their home company for extended periods of time. One manager also warns against the development of a “grey” culture in project firms where different firm cultures are mixed to a bland whole in which specific and colourful elements of individual company cultures are lost. In sum, virtual working may create ambiguity and a lack of belongingness and undermine the identification and trust-building processes that are seen as crucial for effective leadership. Thus, virtual, flexible organizations need leaders to perform integrative functions (Shamir, 17 11212 1999). A top manager of a large organization in the engineering sector describes that project managers in their firm basically run a small enterprise within the company. They need to be able to grasp opportunities, while managing the substantial financial risks. Strong leadership is crucial. In his words: “You need strong people management. If you don’t get the maximum out of the team, you don’t get the maximum for the company. So apart from being tough and holding your team members accountable, and must be able to treat Bill differently from Paul, and Harry differently even again”. In line with this, Cascio and Shurygailo (2003) conclude that research shows that leaders make a critical difference for (traditional) team performance. They also state that: “these findings are just as applicable to virtual teams as they are to teams that interact physically” (p.362). Although integrative leadership roles thus seem important, we do not yet fully understand whether strong, integrative roles of leaders also be performed ‘temporarily’ and ‘at a distance’. Do temporary virtual leaders affect followers as strongly as their more ‘traditional’ counterparts? One integrative form of leadership is transformational leadership (e.g. Bass, 1985; 1997). Keegan and Den Hartog (2004) tested whether the role of transformational leadership in employee affect and attitudes found in more traditional contexts also holds when leadership is a temporary arrangement rather than a permanent one. They found that perceived transformational leader behaviour correlated positively with commitment and motivation and negatively with stress in teams led by line managers, but not in project teams led by project managers. These results suggest that in a temporary project based work arrangement, leadership may have less impact on followers. Our study adds that while managers’ indicate that strong leadership is needed in these contexts, many barriers exist. Such distal and virtual managers often experience ambiguity in reporting relationships, are often less able to exercise the same influence over performance evaluation and careers, and less easily influence identification and trust as 18 11212 compared to their co-located counterparts. If this is the case, the enthusiasm with which some writers embrace the possibilities offered by more virtual, temporary, and flexible ways of organizing may need to be tempered by the possibility that such work arrangements strain crucial leader-follower relationships. References Barker, J.R. (1993) Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams. AdministrativeScience Quarterly, 38: 408-437. Bass B.M. (1985) Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press. Bass, B.M. (1997). Does the transactional - transformational paradigm transcend organisational and national boundaries? American Psychologist 1997; 52(2): 130-139. Burns, T. & Stalker G. (1961).The management of Innovation. London: Tavistock. Cascio,W.F. & Shurygailo, S. (2003). E-leadership and virtual teams. Organizational Dynamics, 31(4), 362-376. Den Hartog D.N., De Hoogh, A.H.B. & Keegan, A. E. (2007) Belongingness as a moderator of the charisma – OCB relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, in press. Den Hartog, D.N. & Koopman, P.L. (2001). Leadership in organizations. In: Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Kepir – Sinangil, H. & Viswesvaran, C. (eds.). Handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology, volume 2. London: Sage. Keegan, A.E. & Den Hartog, D.N (2004). Transformational leadership in a project based environment: a comparative study. International Journal of Project Management, 22, 609-617. Shamir, B. (1999). Leadership in boundaryless organizations: Disposable or indispensable? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 49-71. Zigurs, I. (2003). Leadership in virtual teams: Oxymoron or opportunity? Organizational Dynamics, 31(4), 339-351. 19 11212 VOLUNTARY ENGAGEMENT IN AN OPEN WEB-BASED ENCYCLOPEDIA: WIKIPEDIANS, AND WHY THEY DO IT JOACHIM SCHROER AND GUIDO HERTEL University of Wuerzburg Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia, completely written and maintained by volunteers who collaborate via the Internet (Wikimedia Foundation, 2006). Founded in January 2001, Wikipedia has quickly become one of the 15 most popular websites worldwide (Alexa Inc., 2006) and attracts more than 154 million visitors per month (comScore Networks, 2006). Despite the huge success of Wikipedia, however, little is known about the motivation of its contributors, usually called Wikipedians. As volunteers, many contributors invest a considerable amount of time into researching and writing articles or maintaining the technical infrastructure without receiving any financial compensation for their efforts. Moreover, in contrast to other Internetbased collaboration projects based on voluntary work engagement (e.g., Free and Open Source software development, Hertel, Niedner, & Herrmann, 2003; Moon & Sproull, 2002), Wikipedia has no established public recognition system that might be used as reference in job applications (such as “credit files” in Open Source Software development; cf. Voss, 2005). Thus, the question arises how to explain the high motivation of contributors to Wikipedia. Two theoretical models were integrated to explain the motivation of contributors to Wikipedia. The first model builds on research on social movement participation and civic engagement (Klandermans, 2003; Stürmer & Simon, 2004) and was successfully applied in the context of Free and Open Source Software development (Hertel et al., 2003). The second model builds on research on task characteristic as antecedents of intrinsic motivation and work satisfaction (Hackman & Oldham, 1975, 1980). Because contributors of Wikipedia receive 20 11212 neither financial compensation nor explicit public recognition as authors, task characteristics and intrinsic motivation might be important factors to contribute to the project. According to the model of social movement participation (Klandermans, 2003), the motivation to participate in a social movement depends on subjective expectancy and importance of several motives, which can be categorized into three classes, as well as identification processes: Elements of the first class, norm-oriented motives, refer to expected reactions of significant others, such as friends, family, or colleagues. More favorable reactions of significant others should lead to a higher motivation to participate. The second class of motives, individual costs and benefits include expected gains and losses that are associated with the engagement. Losses in the context of voluntary engagement might be direct costs, such as a donation of money. Moreover, opportunity costs might result from engagement, such as lack of time for other activities or lack of income because the work done is not compensated as it would be in a commercial context. Benefits might include learning, socializing with others, or getting to know other people. The more favorable the expected overall relation of costs and benefits, the higher the motivation to engage in a social movement should be. Third, collective motives refer to the importance of the general goals of a social movement for the individual participant. The higher the importance of the goals (for instance, “freedom of information”), the higher the motivation should be. Fourth, social identification processes should complement these three classes of motives and constitute an independent pathway to social movement participation (Klandermans, 2003; Stürmer & Simon, 2004). Because social identification processes are not part of the original model developed by Klandermans (1997), we will refer to the four motivational components described above as the Extended Klandermans Model (EKM; cf. Hertel, Niedner & Herrmann, 2003). The components are assumed to contribute additively to the motivation of participants in a social movement. 21 11212 Similarly, because the Job Characteristics Model (JCM; Hackman & Oldham, 1975, 1980) conceptualizes task characteristics as antecedents of intrinsic motivation (cf. Deci & Ryan, 2000), satisfaction, and performance in commercial work, similar process are likely to be related to voluntary engagement for Wikipedia. Whereas constructs from social sciences have already been explored in related Free and Open Source Software projects, task characteristics have not been considered in research on voluntary engagement in web-based collaboration so far. Method A web-based questionnaire survey was conducted to explore the motives of contributors to the German version of Wikipedia. The survey was based on an integration of the EKM and JCM, and additional motives were collected for exploratory purposes that might extend the current model. A total of N = 106 contributors to the German Wikipedia participated in our survey. The predominant part (88%) of these participants were male, 10% were female, and 2% did not specify their sex. The mean age was 33 years, with a standard deviation of 12 years, and a range from 16 to 70 years. Results supported the research model to a large extend. As expected, satisfaction with the engagement for Wikipedia was largely determined by the net balance between costs and benefits, identification with the Wikipedia community, and perceived task characteristics. Contrary to our expectations, however, the relation between the net balance of costs and benefits and the extend of engagement was negative rather the positive. In this case, causality might be reversed, such that higher engagement leads to less favorable evaluations of costs and benefits. In other words, tolerance for perceived opportunity costs is required for highly active Wikipedia contributors. On the other hand, and consistent with our expectations, the extent of engagement was positively related to intrinsic motivation, which partially mediated the effect of perceived task 22 11212 characteristics on engagement. Similar to research on task characteristics in volunteer civic engagement (Wehner & Güntert, 2005), autonomy, task significance, feedback from others, and skill variety most strongly characterized the overall task experience in Wikipedia engagement. Thus, similar motivational processes seem to be involved in on-line and off-line volunteer work. The three most prominent categories of motives suggested by Wikipedia contributors in the open questions were related to task enjoyment, information sharing and generativity motives. These results both have implications for theoretical work on antecedents of voluntary work engagement in electronic (“virtual”) work contexts as well as for applied questions how to improve motivation and contribution in Internet communities. Moreover, lessons learned from successful Open Content projects such as Wikipedia might also provide innovative suggestions for web-based knowledge management in business organizations. References Alexa Inc. (2006, October 20). Traffic ranking for wikipedia.org [WWW]. Retrieved October 20, 2006, from http://www.alexa.com/data/details/traffic_details?url=wikipedia.org Chin, W. W., & Newsted, P. R. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using Partial Least Squares. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Statistical strategies for small sample research (pp. 307-341). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. comScore Networks (2006, October 26). Worldwide ranking of top web properties [WWW]. Retrieved November 1, 2006, http://www.comscore.com/press/release.asp?press=1049 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268. Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159-170. Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. London: Addison-Wesley. Hertel, G., Niedner, S. & Herrmann, S. (2003). Motivation of software developers in Open Source projects: an Internet-based survey of contributors to the Linux kernel. Research Policy, 32, 1159-1177. Klandermans, B. (1997). The social psychology of protest. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Klandermans, B. (2003). Collective political action. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology (pp. 670-709). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 23 11212 Moon, J. Y., & Sproull, L. (2002). Essence of distributed work: The case of the Linux kernel. In P. Hinds & S. Kiesler (Eds.), Distributed Work (pp. 381–404). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Stürmer, S. & Simon, B. (2004). Collective action: Towards a dual-pathway model. European Review of Social Psychology, 15, 59-99. Voss, J. (2005). Measuring Wikipedia. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference of the International Society for Scientometrics and Informetrics, Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved October 23, 2006, from http://eprints.rclis.org/archive/00003610/ Wehner, T., & Güntert, S. T. (2005). Wie motivierend ist frei-gemeinnützige Arbeit? [How motivating is voluntary non-profit work?] In GfA (Ed.), Personalmanagement und Arbeitsgestaltung. Dortmund, Germany: GfA Press. Wikimedia Foundation Inc. (Ed.). (2006, October 19). Wikipedia. Retrieved October 19, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia&oldid=82498597. 24 11212 WHY ARE PROJECT MANAGERS WILLING TO WORK IN FULLY VIRTUAL SETTINGS? ROBERT M. VERBURG Delft University of Technology PETRA BOSCH-SIJTSEMA Helsinki University of Technology MATTI VARTIAINEN Helsinki University of Technology More and more firms organize their work through virtual teams in order to cross time zones and distances more easily and to be closer to their customers and markets (Kirkman et al., 2002). Furthermore, global firms experience the geographical distribution of expertise and knowledge as a challenge, and virtual teams may enable them to organize work better and according to the expertise of team members rather than to depend on the local availability of skills and knowledge (Hertel et al., 2005). Collaboration technologies are an important enabler for working virtually. The developments in mobile and wireless information and communication technologies especially create possibilities to work in any place and time. In addition to the technological possibilities, a number of relevant business drivers, such as savings in real estate, travel costs and working around the clock, have led to a wide diffusion of virtual teams (Grimshaw & Kwok, 1998; Wiesenfeld et al., 1999). However, a number of problems associated with working in virtual teams remain. These problems include communication difficulties especially for complex tasks, the quality of the technological support tools, issues of trust building among virtual team members, and, numerous leadership issues (see Hertel et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2004 for overviews). Another may lie in the motivation of managers in such contexts, which is what the study presented here explores. 25 11212 Virtual teams are defined as groups of geographically dispersed employees with a common goal carrying out interdependent tasks using mostly technology for communication and collaboration (e.g., Bell & Koskowski, 2002; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1998). A vast literature is available on the nature and elements of virtual teams. A large chunk of the literature on virtual team work focuses on the team as well as the individual aspects of working virtually. Important topics include the effective use of information technology, the importance of trust in the team, team formation and self management issues. However, few empirical studies focus on the context of virtual work and the reasons for organizing work in a virtual manner. There are also only few studies available that report on fully virtual work within the growing number of global companies. Many studies are conducted among student groups (e.g., Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1998) or focus on the informal open source software development communities, such as the LINUX community. In this paper we will present a study among 30 project managers who are responsible for the output of work within fully virtual settings. The study focuses on the reasons why those managers may opt for organizing their projects virtually. Much work is done in partially rather than fully virtual contexts, although the latter is increasingly found. Fully virtual settings are defined according to the following guidelines: (1) there should be a very low frequency if at all of face-to-face contact between individuals or subgroups; (2) there should be many collaborating units, and (3) all members in a collaborating unit should work through mediated communication. Many global firms work virtually in the form of virtual projects (Rad & Levin, 2003). We define a virtual project as a virtual team with a limited duration (temporality is important). In the study presented here, we collected data on these virtual projects from project managers of global companies who have experience in working in (fully) virtual settings and who have the decision power to design the project organization. 26 11212 Our research focuses on the attributes that increase decision-makers’ willingness to work in fully virtual projects, i.e. what are the perceived benefits and the personal values behind the decisions to work virtually. Values are defined as shared prescriptive or proscriptive beliefs about ideal modes of behaviour and end-states of existence that are activated by the situation (Rokeach, 1980). Values are seen as universal and as vital components for the management of meaning (Cha & Edmondson, 2006). Based on a literature review of the motivations that drive decision makers to work fully virtual, we study the attributes (or benefits) which are important for managers in fully virtual settings. We also address the boundary conditions that managers perceive (why do they want to work virtually and what do they need to do so successfully). In order to link the defined attributes with the motivations of decision makers we apply a Means-End-Chain methodology (MEC) (Reynolds & Gutman, 1988). MEC is a well established method in marketing research to identify short-term benefits and their linkage to long-term human motivations (individual values). This method provides insights into the roots of consumer behavior and at the same time links it to practical attribute profiles of e.g. a product or service. While the methodology is well accepted within the realm of consumer research it is hardly applied for the study of organizational behavior. Our data derives from a qualitative study we performed among extreme virtual teams. Project managers (N = 30) with ample experience with working in extreme virtual teams were interviewed. From these interviews we categorized a number of benefits that were important for working in extreme virtual settings. Several different aspects emerged, which were categorised into: corporate support, communication and trust, project leadership and individual aspects. Examples of such benefits included visibility within the firm and balance in work and personal life. The benefits were linked to individual values and the results of our study indicate that the value of accomplishment was perceived as most important to project managers who had 27 11212 experience in working in fully virtual settings. The reason why accomplishment was found to have such a central role might be based in the importance of performance and delivering results of general project management theory (see Shenhar & Dvir, 1996). Furthermore, within global companies, project managers are often rewarded according to their team’s performance. Project managers are therefore likely eager to focus on team results. In order to reach the accomplishment of goals it was necessary that a number of conditions were fulfilled. These boundary conditions include the corporate support for working in a fully virtual setting, the availability of multi-media support, trust within the team, and clear rules about communication rules. The presence of these conditions will lead to benefits such as faster project conduct, increased project control and alignment of shared goals within the virtual project. This empirical study adds to the literature on virtual teams by assessing managers’ values as well as perceived benefits and boundary conditions related to working in fully virtual projects. It also adds more generally to the organizational behavior and virtual team literature by introducing the MeansEnd-Chain methodology that has been developed in marketing research to these fields. References Bell, B. S. & S. W. J. Kozlowski (2002) “A typology of virtual teams. Implications for effective leadership,” in Group and organization management,, 27 (1): 14-49. Cha, S. E. & A. C. Edmondson (2006) “When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values-driven organization,” The Leadership Quarterly, 17: 57-78. Hertel, G., S. Geister & U. Kondradt (2005) “Managing virtual teams: A review of current empirical research,” Human resource management review, 15: 69-95 Grimshaw, D. J. & F.T. S. Kwok (1998) “The business benefits of the virtual organization,” In Magid Igbaria & Margaret Tan (Eds.), The virtual workplace. Idea group publishing: Hershey, USA: 45-70 Jarvenpaa, S., L. & D. E. Leidner (1999) “Communication and trust in global virtual teams,” Organization Science, 10 (6): 791-815 Kirkman, B. L., B. Rosen, C. B. Gibson, P. E. Tesluk & S. O. McPherson (2002) “Five challenges to virtual team success: lessons from Sabre Inc.,” Academy of management executive, 16(3): 67-79. 28 11212 Martins, Luis L., Lucy L. Gilson & M. Travis Maynard (2004) “Virtual teams: What do we know and where do we go from here?” Journal of Management, 30 (6): 805-835. Rad, P.F. & Levin, G. (2003) “Achieving project management success using virtual teams”, Boca Raton, Florida: J. Ross Publishing. Reynolds, T.J. & J. Gutman (1988) “Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation, Journal of Advertising Research, February/March: 11-31. Rokeach, M. (1980) “Some unresolved issues in theories of beliefs, attitudes and values”. In H.E. Howe, Jr. & M.M. Page (Eds.), 1979 Nebraska symposium on motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Shenhar, A. & D. Dvir (1996) “Toward a typological theory of project management,” Research Policy, 25: 607-632. Wiesenfeld, B.M., S. Raghuram & R. Garud (1999) “Communication Patterns as Determinants of Organizational Identification in a Virtual Organization,” in Organization Science, special issue on communication processes for virtual organizations, 10 (6): 777-790. 29 11212 VIRTUAL TEAM BOUNDARY COMPLEXITY: A TEAM COORDINATION PERSPECTIVE J. ALBERTO ESPINOSA, GWANHOO LEE AND WILLIAM DELONE American University Given current globalization and outsourcing/offshoring trends, many technical projects contexts can be characterized as very virtual and global. Technical projects increasingly employ virtual teams working in complex, geographically distributed collaboration arrangements as organizations seek to develop and implement effective systems for users and customers around the world at lower costs by leveraging internal and external resources (Powell, Piccoli, & Ives, 2004). These virtual teams are divided by various boundaries, including distance, temporal, organizational and cultural (Watson-Manheim, Chudoba, & Crowston, 2002; Orlikowski, 2002; Espinosa, Cummings, Wilson, & Pearce, 2003; Lipnack & Stamps, 1997). These boundaries often co-exist within a given team and the resulting complexity of collaborating across these multiple boundaries becomes an important risk factor for project success. The literature on virtual teams has started to address the concept virtuality or virtualness in teams (Griffith, Sawyer, & Neale, 2003; Kirkman & Mathieu, 2005; Lu, Watson-Manheim, Chudoba, & Wynn, 2006). While this is a step in the right direction, these constructs have limitations in helping us study how teams coordinate their work across complex geographic configurations in teams. Some examples of unanswered questions include: how does virtualness change as the number of locations or time zones changes in a team or as the distribution of team members across these locations or time zones varies? Or, more importantly, how does this affect how teams coordinate their work? While the concept of virtualness is important to characterize and study virtual teams, we suggest that the complexity of the virtual team boundary context helps us better understand the coordination challenges faced by virtual teams. In this research we develop and propose a construct for virtual team boundary complexity that can help us understand how teams can coordinate their work more effectively across these boundaries and suggest some measures to measure this complexity. Coordination is about 30 11212 managing dependencies among task activities (Malone & Crowston, 1994). We posit that it is not the virtual team boundaries themselves that makes it more difficult to manage these dependencies, but the complexity of the virtual team boundary configuration resulting from having to work across multiple boundaries. Therefore, understanding this complexity is very important in figuring out how virtual teams can coordinate their work more effectively. We draw upon data collected by the authors and colleagues for two different research projects (Espinosa, Lee, & DeLone, 2006; Espinosa & Pickering, 2006) to support our arguments. Virtual Team Boundary Complexity and Coordination Effectiveness Virtual team boundaries create barriers that make it difficult for members to communicate and work together (Espinosa et al., 2003; Orlikowski, 2002; Watson-Manheim, Chudoba, & Crowston, 2002). How these various boundaries are arranged within a team can make a big difference. Take for example the familiar outsourcing relationship between a U.S. and an Indian firm working together on a technical project. Team members in this context are in only two locations, but the geographical boundary dividing this team aligns perfectly with organizational, distance, time zone, cultural and language boundaries. This alignment of boundaries creates a “fault line,” which has been argued to be very difficult to bridge (Lau & Murnighan, 1998). However, one of our studies (Espinosa et al., 2006) found evidence that team members in two such locations adjusted quite well and learned how to operate effectively with each other because the location, time, organizational, cultural and language differences were well understood by all, such that team members were able to implement effective coping mechanisms (e.g., shift work hours, more detailed documentation, use of mobile communication devices, etc.) to work together. In contrast, the other study (Espinosa & Pickering, 2006) found that when a team operates in several locations spanning multiple time zones, cultures, languages, and organizations things become more unpredictable and the team has a more difficult time finding a rhythm to coordinate their work effectively. In fact, there were so many locations and time zones 31 11212 represented in one team we studied that team members shifted their work hours so dramatically that some co-located team member had non-overlapping work hours. We refer to this diversity of boundaries as “virtual team boundary complexity.” Wood (1986) argued that task complexity increases when more information cues need to be processed to carry out the task and indicated that tasks not only have a “structural” component that is inherent to the task, but also have a “coordinative” complexity that is affected by the task context. For example, when a task is carried out by many team members their actions need to be coordinated, adding further complexity to the execution of the task. When the context makes it difficult to exchange the information cues necessary to carry out the task – i.e., the task context is more complex – it affects the team’s ability to coordinate the task, but this complexity is not captured in the concept of virtualness. The virtualness dimensions proposed in the literature include: physical distance among team members; level of technology support; percentage of time apart in the task (Griffith et al., 2003); synchronicity – to distinguish between “real-time” and “lagged-time” interaction (Kirkman & Mathieu, 2005); and workplace mobility – to capture the extent to which team members work at various sites, telecommute and use mobile devices (Lu et al., 2006). These dimensions are useful but have limitations in helping us understand coordination, particularly when teams are dispersed in more complex geographic configuration arrangements involving several sites. For example, some teams may be widely dispersed (i.e., balanced), while others may have the majority of members in one site with a few isolated members in other sites (i.e., unbalanced) (O'Leary & Mortensen, 2005), and some teams may be dispersed on a North-South axis with little time zone difference, while others may be dispersed along an East-West axis with substantial time zone differences (Espinosa & Pickering, 2006; O'Leary & Cummings, 2002). We argue that coordination is affected when virtual team boundary arrangements make it difficult to communicate – i.e., coordinate “organically” – because the team is forced to coordinate “mechanistically” using task programming mechanisms like schedules, plans, and 32 11212 division of labor, which are not as effective when task conditions are less routine (March & Simon, 1958). While each type of boundary will have its unique effects on communication, we argue that the overall communication effectiveness in the team and, therefore, its ability to coordinate organically will be generally affected by four dimensions: (1) the different of types of boundaries spanned by the team; (2) the average number of boundaries present for each boundary type; (3) the extent to which these boundaries align; and (4) the dispersion of members across these boundaries. Consequently, we propose that these dimensions define a virtual team’s boundary complexity. We base this proposition on the fact that these dimensions increase the amount of information cues that needs to be processed by team members to coordinate their work effectively (Wood, 1986). We now discuss why. Members in teams that span more boundary types (e.g., distance, time zones, organizational, cultural) need to keep in mind more information about their teammates to communicate effectively (Espinosa et al., 2003). Similarly, team members will also have more difficulty communicating and coordinating when there are more boundaries within the various boundary types. For example, it is more difficult to coordinate work when teams operate across several locations (O'Leary & Cummings, 2002) or across multiple time zones (Espinosa & Pickering, 2006) than when the there are only two or three locations or time zones. Boundary alignment can also affect communication and coordination. While Lau and Murnighan (1998) suggested that it is more difficult to work together when boundaries align, the data in our studies show that team members adjust and learn how to bridge these multiple but aligned boundaries (Espinosa et al., 2006), whereas multiple misaligned boundaries create more confusion about how and when to interact (Espinosa & Pickering, 2006). Finally, the dispersion of team members across boundaries can make a big difference. Overall, we expect that more widely dispersed (i.e., balanced) configurations across boundaries makes it more difficult to coordinate than with unbalanced configurations. For example, a team with a high concentration of members in the US and a few isolated members in other countries, or with a high concentration of Indian engineers 33 11212 will have a larger number of members that have little difficulty communicating effectively, whereas teams with membership widely scattered across locations and cultures will need to bridge boundaries to communicate and coordinate. We are in the process of collecting data to validate this construct to be used as a key independent variable predicting coordination in a related study. References Espinosa, J. A., Cummings, J. N., Wilson, J. M., & Pearce, B. M. (2003). Team boundary issues across multiple global firms. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 157-190. Espinosa, J. A., Lee, G., & DeLone, W. (2006). Global boundaries, task processes and is project success: A field study. Information, Technology and People, 19(4), 345-370. Espinosa, J. A., & Pickering, C. (2006). The effect of time separation on coordination processes and outcomes: A case study. Paper presented at the 39th Hawaiian International Conference on System Sciences, Poipu, Kauai, Hawaii. Griffith, T. L., Sawyer, J. E., & Neale, M. A. (2003). Virtualness and knowledge in teams: Managing the love triangle of organizations, individuals, and information technology. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 265-287. Kirkman, B. L., & Mathieu, J. (2005). The dimensions and antecedents of team virtuality. Journal of Management, 31(5), 1-19. Lau, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (1998). Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 325-340. Lipnack, J., & Stamps, J. (1997). Virtual teams: Reaching across space, time, and organizations with technology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Lu, M., Watson-Manheim, M. B., Chudoba, K. M., & Wynn, E. (2006). How does virtuality affect team performance in a global organization? Understanding the impact of variety of practices. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 9(1), 4-23. Malone, T., & Crowston, K. (1994). The interdisciplinary study of coordination. ACM Computing Surveys, 26(1), 87-119. March, J., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York: John Wiley and Sons. O'Leary, M. B., & Cummings, J. N. (2002). The spatial, temporal, and configurational characteristics of geographic dispersion in teams. Paper presented at the Presented at the Academy of Management Conference, Denver, Co. O'Leary, M. B., & Mortensen, M. (2005). Subgroups with attitude: Imbalance and isolation in geographically dispersed teams. Paper presented at the Presented at the Academy of Management Conference, Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii. Orlikowski, W. (2002). Knowing in practice: Enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organization Science, 13(3), 249-273. Powell, A., Piccoli, G., & Ives, B. (2004). Virtual teams: A review of current literature and directions for future research. Data Base for Advances in Information Systems, 35(1), 6-36. Watson-Manheim, M. B., Chudoba, K., & Crowston, K. (2002). Discontinuities and continuities: A new way to understand virtual work. Information, Technology and People, 15(3), 191– 209. 34 11212 Wood, R. E. (1986). Task complexity: Definition of the construct. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37(1), 60-82. 35