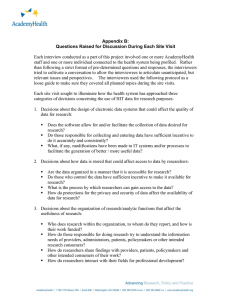

Bridging Research and Policy

advertisement