JCMS Symposium: EU Governance After Lisbon

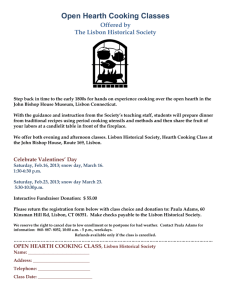

advertisement