NOTES – DO NOT QUOTE AND DISTRIBUTE PUBLICLY

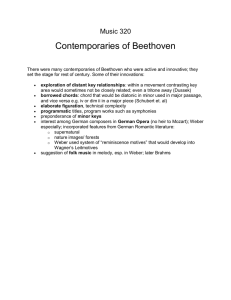

advertisement

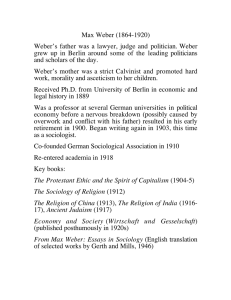

NOTES – DO NOT QUOTE AND DISTRIBUTE PUBLICLY Lecture : Grappling with modernity – Weber/Gramsci Why Weber and Gramsci? One might say, hm, one is German, one Italian - they’ve never met although they lived roughly at the same time (Weber dies 1920’; Gramsci 1937), Weber is clearly not a Marxist but liberal - -Gramsci clearly is and he goes to prison for his convictions in fascist Italy, as we shall hear in moment. They both lived and wrote in rather different world, political, economically and socially. But there is something that unites them – despites all these difference and which also links them to the man we discussed in week 5, Karl Marx. Now what is that? In their writings they both tried to come to terms with capitalism but a capitalism that was different from Marx who tended to focus on England. Weber and Gramsci lived in countries that were hit by industrial capitalism much later than England who was going through it since the 18th century (industrial revolution); For German’s felt its consequence of industrial capitalism -- on the environment and society -- really only in the late third of the 19th century – it virtually exploded and men like Weber saw the world they grew up in crumbling around them. Gramsci’s Italy was even more behind and remained largely agrarian. Now both men, we claim here today, were engaging with Marx’s materialism – who was very big at their time – and were trying to adjust it his ideas to these different situation. Let me summarise in my introduction here some of the central themes of Marx. Aditya will accuse me of vulgar Marxism but never mind – I just want to remind you of the basics. Marx material conception of history We remember that Marx set out to contradict Hegel; he wished to overthrow the Hegelian notion that ideas, in the form of "spirit", were the essential factors in history, and instead depicted ideas as dependent, in their genesis and functioning on material factors. These factors are found primarily in a society's economic institutions Marx as we remember divided society into three parts: Productive forces: Machinery, raw materials and skills, land etc. Give rise to ‘relations of production’: relations between people/and or people and things – these relations constitute the ‘economic structure of society, and it in turn gives rise to the ‘superstructure or the political, legal, cultural institutions in which member of that society conceive themselves and their relations. Every society, according o the sociology of Marx, has a set of economic institutions, a social relationship system allocating roles in the production, distribution and utilization of goods. This system is organized around a society's production technology, and is acutely responsive to changes in technological complexity and efficiency. Roles in the economic system determine roles in the status system: broad strata of the population group together in terms of economic similarities. Taken together, these two systems constitute a class system, and the members of a given class share common interests, values and a style of life. The allocations dictated by the economic system determine not only difference in status, for they include difference in political power as well. Thus the way to understand the functioning of a total society is to treat its economic institutions as the key variable. We say that history changes when the forces of production change, which then trigger a change in the relations of production and so. All societies re in a continual process of change. Changes in material factors determine the direction of historical change for the society as a whole. Indeed, major processes of historical change are inconceivable without a material basis in the sense of a change in economic institution. What Marx is not interested in that much – and even less so his followers –are the individual and explaining motivations, the relationship between individual motivation and general concensus in a society. 2. Concepts of motivation for Marx: emphasizes the role of purely external pressures on individuals: physical force, fraud and compulsion He is aware however that there is a consensus which is achieved by people doing things without being forced into it and explains it in the following way: Position in a class endows an individual with a set of interests, a stake in certain present aspects of the society, or a potential for gain should the society undergo changes. For Marx these interests are, it seems to us now, more or less intuitively or rationally understood by the members of a class or their political leaders. But, in perhaps the more common case, class interests determine action indirectly, and are effective through the medium of an ideology, an elaborated rationalization of a set of class interests. This ideology, in Marxist terms, comprises values as well as belief-systems imperatives as well as world-image. PROBLEM: Although this theory may account for uniformities in the motivation of members of a single class, it had yet to account for consensual phenomena of an inter-class sort. To meet this difficulty, Marx advanced the proposition that the class which control the means of production could and did impose its ideology on the rest of society. The failure of the members, leaders or ideologists of a class to comprehend their real interests leads them to accept the ideology of another, opposed, stratum and so underlies this imposition. At this point Engel, Marx collaborator, introduces the notion of ‘false consciousness’ which he defined as a process by which men incorrectly assess the sources of their beliefs attributing these to the history of thought, for instance, rather than to their real roots in the system of production In sum: Marx, if you like failed to specify the mechanisms by which common values are produced – and that became a problem for later generations of scholars engaging with his views. Now this is where we get to Weber and Gramsci. Christos and I will claim that they both are trying to account for this lack. And they are trying to account for it by using new ideas about individual and collective motivation – unknown to Marx at the time. Both of them in different ways use what becomes rather big at their time and we now call ‘psychology’. They are using these ideas to account for how one might want to explain achieve ‘common values’ and how people from different classes – who ought to be engaged in class struggle – agree. Let me know turn to Weber: (history of story of Weber) What are these new ideas of the individual and the collective which are flowing around? We see the rise of experimental psychology (in Germany by physicians like Wundt); experimentally understanding human behaviour We also have the huge interest, coming from France in Crowd physicolgy – a man called Gustave le Bon (the Crowd and the study of the popular mind, 1895 – very much discussed in Germany. We have the rise of the theories of Sigmund Freud, his idea that there is not only a consciousness but a ‘unconciousness’. People are driven by their repressed feeling, thoughts and emotions. It has been argued that these ideas about the human mind and collective action are also inspired by capitalism and I think this is probably correct. Important for us to remember is that these ideas are around at the time Weber and Gramsci write and they shape their thinking about individual and collective action and motivation. For Weber important is also the rise of a particular way of thinking about knowledge: Positivms –the idea that all knowledge is gained strictly by observing and collecting facts – ideas of objectivity and neutrality etc. Now, how is Weber approaching the topic in his proestant ethic? 1. Focus on individual Weber is adamant that the fundamental unit of investigation must always be the individual. He thus focuses upon the individual and not on groups or collectives; only the individual he believes is capable of ‘meaningful’ social action. As far as the ‘subjective interepretation of action’ is concerned, ‘collectives must be treated as soleley the resultants and modes of organisation of the particular acts of individual persons: (slide here) ‘for sociological purposes there is no such thing as a collective personality, which ‘acts’. When reference is made in a sociological context to a state, a nation, a corporation, a family or army corps, or to similar collectives, what it means is … only a certain kind of development of actual or possible social action of individual persons.’ (Weber, economy and Society, 1968, p. 13) Collectives cannot feel, cannot think, perceive, only individual people can. To assume otherwise, Weber argues is to impute a spurious reality to what are in effect conceptual abstractions. Furthermore he argues that the task of the socioligst -- a scholar who is interested in understanding the ‘togetherness’ of people – to penetrate the subjective understandings of the individual, to get at the motives for social action. 1. Verstehenssoziologie (slide) ‘…the science which attempts the interpretative understanding (deutend verstehen) of social action in order thereby to arrive at a casual explanation of its course and effects’ (Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 1980, p.1) According to Weber sociology attempts to ‘understand’ (verstehen) human action not only the past but also in the present – (being a historicist he of course believed that one needed to understand the past to get at the present…) Distinction to the natural sciences which ‘explain’ (erklaeren) nature. He therefore calls his way of doing socioloty ‘Verstehensoziologie’ (and you find him often therefore labelled as an ‘antipositivist’ – which is not totally correct as we shall see…) What is meant by this is the attempt to comprehend social action through a kind of empathetic liaison with the actor on the part of the observer. The strategy is for the investigator to try to identify with the actor and his or her motives and to view the course of conduct through the actor’s eyes rather than his own. Protestant ethics and the problem of rationalisation The ‘Protestent ethics’ was to the frist study of a much broader and truly global enterprise, an investigation into the relationship between economics and religion. (he writes other works on China, buddism. In English in 1930. To reduce his book to the simple formula – Calvinism was the principal cause of capitalims is far too simplistic. In fact the case he present is replete with ambiguities, inconcistencies and other intellectul curiosity, which he does not solve or wipe out to state his thesis. He leaves these problems in the text and it is therefore a difficult text to understand and fertile ground for misinderpretation – or I should say productive misinterpretations. The text deals with religion but at its core it deals with a problem that fastinated Weber all his life, the problem of ‘rationalisation’ in modern culture. Just remember what I’ve said at the beginning of his time. The rise of industrialisation and its rationalisation of labour; also the ‘rationalisation’ of nature through the natural sciences..they believe that they grasp nature by reason and mathematics; (slide) By rationalisation, Weber referred to a ‘set of interrelated social processes by which the modern world had been systematically transformed’. Or to phrase it otherwise, rationalisation refers to a process in which an increasing number of social actions become based on considerations of teleoigical efficiency or rational calculation rather than rather than on motivations derived from morality, custom or tradition. Okay back to the PE itself. Weber starts off the book by explaining tendencies in the society of his time that appear typical and universal. He observed a general resistance to personal subservience, reflecting a decline in kinship solidarity And that economic conduct seemed to possess an ethical content of its own. Weber argues that the idea of hard work as a duty that carries its own intrinsic reward is a typical attribute of man in modern capitalist world. A man should work well in his gainful occupation, not merely because he had to but because he wanted to; it was a sign of his virtue and a source of personal satisfaction. ‘it is an obligation which the individual is supposed to feel and does feel towards the content of his occupational activity, no matter in what is consists’, Weber argues. Hard work is a virtue and hence a moral obligation. It is these ideas and habits that favor a rational pursuit of economic gain, in fact, it stands at the basis of what Weber comes to call ‘rational capitalism’. There are other forms of capitalism all over the world and he lables them as you remember in his book: The ‘booty capitalism of robber barons, the pariah capitalism of general commercial activity encouraged by usury; the traditional capitalism of large-scale undertakings. But only the form of ‘rational capitalism’, characterised by a systematic pursuit of profit through the employment of free labour, and the combination of a disciplined labour force, and the regular investment of capital is a Western phenomenon. Only in the West argues Weber can we find the accumulation of capital for its own sake. Now, how do we come to this ‘rational capitalism’? Th accumulsyion of capital for its own sake. Now, for Weber it had to do with the development of a certain moral attitude, which considered ‘work as a moral obligation’. This maxim represents the ‘modern spirit of capitalism’ for him. Of course, he said, in its modern form this spirit of capitalism is devoid of all higher transcendental purpose. Orginally, however, he reminds us, this spirit had profound religious significance. It has religiously grounded. It was to this religious past of the ‘capitalistic spirit’ that Weber turned his attention to in the book you’ve read. And he looked for its origin in the religious ideas of the Reformation. Weber sets out to solve what he saw as a paradox. He wanted to show how certain types of Protestantism became a fountainhead of incentives that favoured the rational pursuit of economic gain. Worldly activities had been given positive spiritual and moral meaning during the Reformation. Strangely however at recisely a time in which economic gain was officially desposed by all religious leaders. In order to understand this paradox Weber believed it necessary to analyse certain theological doctrines of the Reformation. Now, none of the great Reformers had any thought of ‘promoting the spirit of capitalism’ of course but Weber aimed to show that their doctrines nevertheless contained incentives in this direction. And he particular was interested in Calvinism and its doctrine of predestination, according to which each individual’s state of grace was determined by God’s inexorable choice, from the creation of the world and for all times. It as impossible for the individual to whom it had been granted to lose God’s grace as it was for the individual to whom it had been denied to attain it. John Calvin who figure that out, claimed that we can only know that some men are safed and the rest are damned. However, we can never know who the chosen person is! That is the trick. Weber believed now that this ‘message’ that the ordinary man was bound to feel profoundly troubled by a doctrine that did not permit any outward sign of his state of grace and that imparted to the image of God such terrifying majesty that He transcended all human entreaty and comprehension. Before his God, man stood alone. The priest could not help because the elect could understand the work of God only in their own hearts. Sacraments could not help because their strict observance was not a means of attaining grace. Calvin had taught that one must find solace solely on the basis of the true faith. Each man was duty-bound to consider himself chosen and to reject all doubt as a temptation of the devil. A lack of self-confidence was interpreted as a sigh of insufficient faith. To attain that self-confidence, unceasing work in a calling was recommended. By his unceasing activity in the service of God, the believer strengthened hs selfconfidence as the active tool of the divine will. This idea implied a tremendous tension: Calvinism had eliminated all magical means of attaining salvation. In the absense of such means the believer could not hope to atone for hours of weakness or of thoughtlessnesss by increased good will at other times…There was no place for the very human Catholic cycle of sin, repentance, atonement, release, followed by renewed sin …The moral conduct of the average man was thus deprived of its planless and unsystematic character …Only a life guided by constant ‘thought’ could achieve conquest over the state of human sinful nature. It was this rationalisation, which gave the Reformed Calvinist faith its peculiar ascetic tendency …(ciritque: W inferred a psychological condition – the feeling of religious anxiety – from an analysis of doctrines and institutions.) And it was this ascetic tendency that explained for Weber the affinity between Calvinism and the ‘spirit of capitalism’. He demonstrated how Calvinism doctrines provided effective incentives for the layman by examining pastoral writings of Puritan divines such as the English Richard Baxter or the works of Benjamin Franklin. They praise work as a defense against all such temptations as religious doubt, the sense of unworthiness, or sexual desires. In this negative sense the praise of work gave rise to a detailed code of conduct. To waste time is a deadly sin, for the span of life is too short and prescious and man must use his every minute to serve the greater glory of God and make sure of his ‘election’. What developed was an ethic of unremitting commitment to a worldly calling/duty/task (the workd and role one was called by God to fulfil). Economic productivity was higher in Protestant communicities than it was in Catholics, even in modern times, because it was the practical result of such old ethical beliefs and practices, Weber said. The most rapid possible accumulation of capital was the sign of the elect. In his Protestant ethic Weber did not go substantially beyond the analysis of theological doctrines and pastoral writings. He aimed to show that the inherent logic of these doctrines and of the advice based upon them both directly and indicrectly encouraged planning and self-denial in the pursiuit of economic gain. He stated that he investigated specifically: (image) ….whether and at what points certain ‘elective affinities’ are discernible between particular types of religious beliefs and the ethics of work-a-day life. By virtue of such affinities the religious movements have influenced the development of material culture, and (an analysis of these affinities) will clarify as far as possible the manner and the general direction (of that influence)…We are interested in ascertaining those psychological impulses which originated in religious belief and the practice of religion, gave direction to the individual’s everyday way of life and prompted to adhere to it’. It is important to point out that all this was the unintional consequence of claims that dedication to a calling (Beruf) was a path to God’s favour and grace, as was thriftiness in consumption. Over the centuries the religious aspect of this ethical ‘calllig’ got lost but it continues to shaped people’s behaviors. The bourgois classes, Weber claimed, in the West have accumilated tremendous wealth, due to this specific ascetic attitude to life. Webers famously coins the saying that it had become our ‘iron cage’, from which we can never escape and which keeps us going on like a hamster in its wheel. (slide) of his deep trouble. Weber saw this process going on in all areas of his contemporary life; he perceived what he described a ‘disenchantment of modern life’. For example he saw the rise of capitalist society as an illustration of this general pattern of rationalisation. As a social process, rationalisation includes the systematic application of scientific reason to the everyday world and the intellectualisation of routine activities through the application of systematic knowledge to practice. Rationalisation. more generally, in everyday life was also associated with the disenchantment of reality, that is the secularisation of values and attitudes. In institutional terms, this process involved the decline of the authority of the Church, and the erosion of the status of the clergy. In religious terms, rationalisation involved the development of the intellectual stratum of theologians who produced religious thought as a systematic statement about reality. Within the political sphere, it was associated, with the decline and disappearance of traditional norms of legitimicay, such as the dependence upon charismatic leadership of kings for example. In social terms, generally, rationalisation was constituted by the spread of bueurocratic control, the establishment of modern systems of surveillance, the dependence on the nationstate as a controlling agency and the rise of new forms of administration. Rationalisation as a master theme in Weber’s work has therefore often been compared with the themes of ‘alienation’ and ‘estrangement’ in the work of Marx, the other great German thinker on capitalism. (I’ll come back to this relationship at the end of my talk.) The question of ‘rationalisation’ is key in his Protestant ethics.