Children of the Valley Framing a Regional Agenda Lead Authors

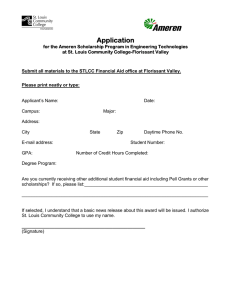

advertisement